The Economics of Happiness

This emerging field broadens economic analysis by using measures of subjective well-being to help address a core issue in economics–how to make best use of scarce resources–by redefining "best use." It is now more than 40 years since Richard Easterlin first advocated using measures of subjective well-being to judge the quality of life.1 I came to see the necessity of such a broadening only after seeing that it was inadequate to assess the consequences of democracy2 and of social capital3 solely in terms of their linkages to economic growth.

Measures of subjective well-being seemed like natural candidate measures of welfare. But to understand and assess their suitability required a broader disciplinary perspective. A useful starting point was to see if life satisfaction assessments from around the world supported Aristotle's prediction that people would report higher life satisfaction if they had better life circumstances, in the form of family, friends, good health, and sufficient material means, while also being supported from the one side by positive emotions and on the other by a sense of life purpose. Aristotle's presumptions were supported remarkably well by World Values Survey data, with two-level modeling revealing the joint importance of individual and national-level variables.4 The fact that life evaluations could be explained by income and other life circumstances permitted calculation of compensating differentials to compare the relative importance of different aspects of life.5

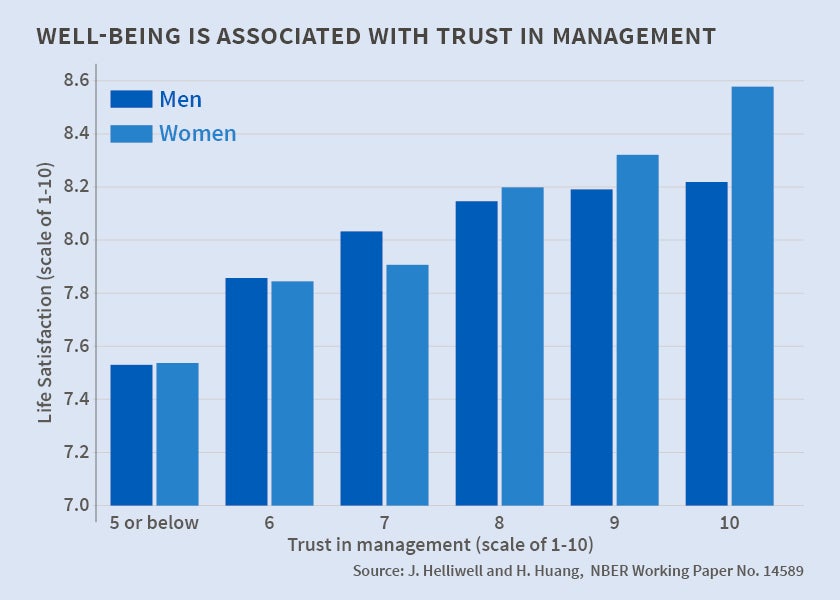

My subsequent work expanded the analysis to show that life evaluations depend more on the quality of government than on the institutions of democracy,6 especially when the former is at low levels, that workplace trust, as shown in the figure, is a very strong predictor of life satisfaction, even more so for women than men,7 and that the quality and quantity of social connections at work, at home, and in the neighborhood are perhaps the most important supports for life satisfaction.8

But what about suicide in those supposedly happy Scandinavian countries? A proper answer to this question required expertise from other disciplines. How well are modern international differences in suicide rates explained by the same factors exposed by Émile Durkheim's careful research more than a century ago?9 Can the same model consistently explain both life satisfaction and suicide rates? World Values Survey data showed that the same factors that had been found to be associated with international differences in life satisfaction were also associated with international differences in suicide rates, of course with the signs reversed. Sweden fit both models perfectly. Its very high subjective well-being and fairly average suicide rates were reconciled by the differing relative importance of some factor–such as divorce, religion, and government quality–between the suicide and life satisfaction models.10 Social trust and community connections were strongly and equally important in both models. Indeed, subsequent research suggested that higher levels of social trust were associated with significantly lower death rates from both suicides and traffic fatalities.11

The apparent usefulness of happiness data spurred deeper digging and a mixture of research methods to untangle two-way linkages between subjective well-being and other variables. It also led to research to establish the meaning and value of different ways of measuring subjective well-being,12 to assess the extent to which there are interpersonal and international differences in how happiness is measured and determined, to evaluate the extent to which the well-being effects of income and other factors depend on comparisons with others,13 and to use subjective well-being data to focus on the quality of economic development.14

Three recent sets of results invite special attention.

Life Evaluations versus Emotional Reports

It is important to distinguish two importantly different measures of subjective well-being: life evaluations and emotional reports. The former are represented by three main types of survey question: How satisfied are you with life as a whole these days? How happy are you with your life these days? and the Cantril ladder, used in the Gallup World Poll, asking people to evaluate their lives today on a scale with the best possible life as a 10 and the worst possible life as a zero. These three ways of evaluating lives deliver answers that are structurally identical, in the sense of being explained by the same variables with the same coefficients, despite having distributions with different means.15 Emotional reports, or measures of affect, can be either positive or negative, and generally refer to either current emotions or those in a recent time period, usually yesterday. Typical measures of negative affect would be worry, anger, depression, and anxiety, with typical measures of positive affect including happiness and enjoyment, sometimes buttressed with more evidently behavioral measures like smiling and laughter. People answer life evaluation questions and reports of emotions yesterday in appropriately different ways, with weekend effects appearing for yesterday's emotions but not for life evaluations.16 Life evaluations, much more than current or remembered emotions from yesterday, are linked strongly and durably to levels and changes in a variety of life circumstances, both within and among countries.17 These include not only individual life circumstances, such as income and unemployment,18 but also the quality of public institutions, ranging from prison conditions19 to the honesty and overall efficiency with which public services are delivered.20

The Power of Generosity

Two of my recent co-authored papers, relying on a mixture of experimental lab studies and international survey evidence, find that people are happier performing pro-social acts. The first paper combined experiments in several different cultures with survey data from many countries to argue that the happiness-producing power of generosity could be a psychological universal rather than something bound by the social norms of specific cultures.21 The second paper used a range of experiments to show that offering a chance to donate, in the context of an experiment set up for other reasons, led to high donation levels and significantly positive emotional effects for givers compared either to controls or to non-givers. Those who were offered, but did not take, the chance to donate felt some emotional costs, but in the aggregate these were much less than the emotional returns to those who chose to donate.22

Marriage and the Set Point for Happiness

If measures of life satisfaction are to be reliable guides to human welfare, they must be shown to respond in predictable and durable ways to changes in important life circumstances. If, on the contrary, there is a happiness set point, determined chiefly by genetic factors, for each individual, with eventual full adaptation to any change in circumstances, then the happiness measure in question will not be able to provide a long-term guide to the quality of life. This view seems to be supported by the finding that post-marriage life evaluations among respondents in the U.K. Household Panel survey returning to pre-marriage levels within a few years demanded our attention. The frequent finding that married people are on average happier than singles in otherwise the same life circumstances has been interpreted by some as showing only that already-happy people were more likely to get and stay married.

In a recent working paper,23 Shawn Grover and I explain the return to baseline by defining the comparison group closely. Although the individuals studied did indeed return to their pre-marriage levels of life satisfaction, they were still happier than they would have been without getting married, since most of the marriages were occurring at ages when the average life satisfaction was dropping, as part of a U-shaped age pattern of life satisfaction in many countries. In addition, the pre-marriage baseline was set too close to the point of marriage, thus already incorporating the happiness created when the long-term relationship was established with the eventual marriage not yet taken place. To be really convincing, however, our research needed to make full allowance for the reverse effects running from happiness to marriage. We did this by including each individual's measured life satisfaction several years in the past to capture any set point effect.

Finally, in attempting to find an explanation for the size and long duration of the happiness effects accompanying marriage in our U.K. sample, we took advantage of a question in another part of the survey asking each respondent to identify their best friend, with spouse or equivalent being one of the categories offered. The life satisfaction effects of being married, relative to being single, were always large and significant, and were more than 50 percent larger for those who reported their spouse as their best friend. The same relationship was also evident for the growing group who were living as a couple but not married–they were on average happier than the singles, but especially so if they regarded their partner as their best friend.

Thus the research showed large and durable life satisfaction effects from a key change in life circumstances, reconciled the life-course and cross-sectional estimates, and developed evidence for a social and friendship-based basis for the well-being benefits of marriage. The paper thereby supports both the ability of life satisfaction measures to capture the well-being effects of changes in life circumstances and the importance of social factors in explaining levels and changes of life satisfaction.

Endnotes

R. A. Easterlin, "Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence," In P. A. David and M. W. Reder, eds., Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz, New York, New York: Academic Press, 1974, pp. 89-125.

J. F. Helliwell, "Empirical Linkages between Democracy and Economic Growth," NBER Working Paper 4066, May 1992, and British Journal of Political Science, 24(2), 1994, pp. 225-48.

J. F. Helliwell and R. D. Putnam, "Economic Growth and Social Capital in Italy," Eastern Economic Journal, 21(3), 1995, pp. 295-307; and J. F. Helliwell "Economic Growth and Social Capital in Asia," NBER Working Paper 5570, February 1996, and in R. G. Harris, ed., The Asia-Pacific Region in the Global Economy: A Canadian Perspective, Calgary, Canada: University of Calgary Press, 1996, pp. 21-42.

J. F. Helliwell, "How's Life? Combining Individual and National-Level Variables to Explain Subjective Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 9065, July 2002 and in Economic Modelling, 20(2), March 2003, pp. 331-60.

J. F. Helliwell and C. P. Barrington-Leigh, "How Much is Social Capital Worth?" NBER Working Paper 16025, May 2010, and in J. Jetten, C. Haslam, and S. A. Haslam, eds., The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-Being, London, United Kingdom: Psychology Press, 2012, pp. 55-71.

J. F. Helliwell and H. Huang, "How's Your Government? International Evidence Linking Good Government and Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 11988, January 2006, and British Journal of Political Science 38(4) , 2008, pp. 595-619.

J. F. Helliwell and H. Huang, "Well-Being and Trust in the Workplace," NBER Working Paper 14589, December 2008, and Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), May 2011, pp. 747-67.

J. F. Helliwell and R. D. Putnam, "The Social Context of Well-Being," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences, 339(1499), 2004, pp. 1445-56.

E. Durkheim, Le Suicide. tude de Sociologie, Paris, France: Félix Alcan, 1897. See also the English translation Suicide: A Study in Sociology [1897] by J.A. Spaulding and G. Simpson, Glencoe Ill., Free Press, 1951.

J. F. Helliwell, "Well-Being and Social Capital: Does Suicide Pose a Puzzle?" NBER Working Paper 10896, November 2004, and Social Indicators Research, 81(3), May 2007, pp. 455-96.

J. F. Helliwell and S. Wang, "Trust and Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 15911, April 2010, and International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1), January 2011, pp. 42-78.

J. F. Helliwell and C. P. Barrington-Leigh, "Measuring and Understanding Subjective Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 15887, April 2010, and Canadian Journal of Economics 43(3), August 2010, pp. 729-53.

C. P. Barrington-Leigh and J. F. Helliwell, "Empathy and Emulation: Life Satisfaction and the Urban Geography of Comparison Groups," NBER Working Paper 14593, October 2008. See also J. F. Helliwell and H. Huang, "How's the Job? Well-Being and Social Capital in the Workplace," NBER Working Paper 11759, November 2005, and Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 63(2), 2010, pp. 225-28.

J. F. Helliwell, "Life Satisfaction and Quality of Development," NBER Working Paper 14507, November 2008. Forthcoming in Policies for Happiness, Oxford University Press, edited by S. Bartolini, E.Bilancini, L. Bruni and P. Porta.

J. F. Helliwell, C. P. Barrington-Leigh, A. Harris and H. Huang, "International Differences in the Social Context of Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 14720, February 2009, and in J. F. Helliwell, E. Diener and D. Kahneman, eds., International Differences in Well-Being, New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 291-350.

J. F. Helliwell and S. Wang, "Weekends and Subjective Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 17180, July 2011, and Social Indicators Research, 116(2), April 2014, pp. 389-407.

See Table 2.1 of J. F. Helliwell and S. Wang, "World Happiness: Trends, Explanations and Distribution," in J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard and J. Sachs, eds., World Happiness Report 2013, New York, New York: United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, September 2013.

J. F. Helliwell and H. Huang, "New Measures of the Costs of Unemployment," NBER Working Paper 16829, February 2011, and in Economic Inquiry, 52(4), 2014, pp. 1485-1502. This paper shows that the spillover well-being losses of local unemployment on those still employed are in aggregate larger than the individual costs for the unemployed themselves.

J. F. Helliwell, "Institutions as Enablers of Wellbeing: The Singapore Prison Case Study," International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(2), 2011, pp. 255-65.

J. F. Helliwell, H. Huang, S. Grover and S. Wang, "Empirical Linkages Between Good Government and National Well-Being," NBER Working Paper 20686, November 2014.

L. B. Aknin, C. P. Barrington-Leigh, E. Dunn, J. F. Helliwell, R. Biswas-Diener, I. Kemeza, P. Nyende, C. E. Ashton-James, M. Norton, "Prosocial Spending and Well-Being: Cross-Cultural Evidence for a Psychological Universal," NBER Working Paper 16415, September 2010, and Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), April 2013, pp. 635-52.

L. B. Aknin, G. Mayraz, and J. F. Helliwell, "The Emotional Consequences of Donation Opportunities," NBER Working Paper 20696, November 2014.

S. Grover and J. F. Helliwell, "How's Life at Home? New Evidence on Marriage and the Set Point for Happiness," NBER Working Paper 20794, December 2014.