Program Report: Health Care, 2019

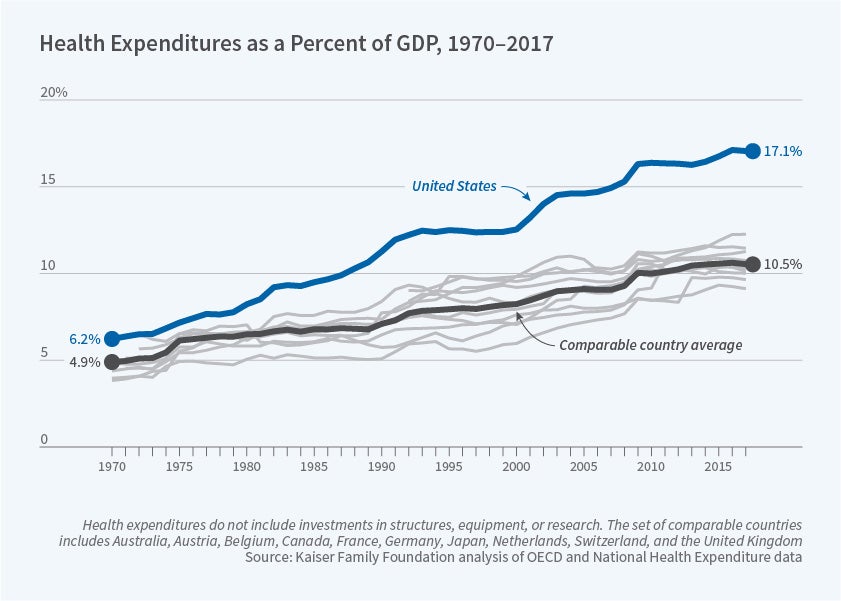

The rise of the US health-care sector over the past several decades has been remarkable. As Figure 1 shows, in 1970, the country devoted slightly more than 6 percent of GDP to health care, about 1 percent more than other nations. Today, the nation devotes almost 18 percent of GDP to health care, which is larger than spending on cars, clothing, food, furniture, housing, fuel, and recreation combined — and is a full 8 percent above the average in comparable countries.

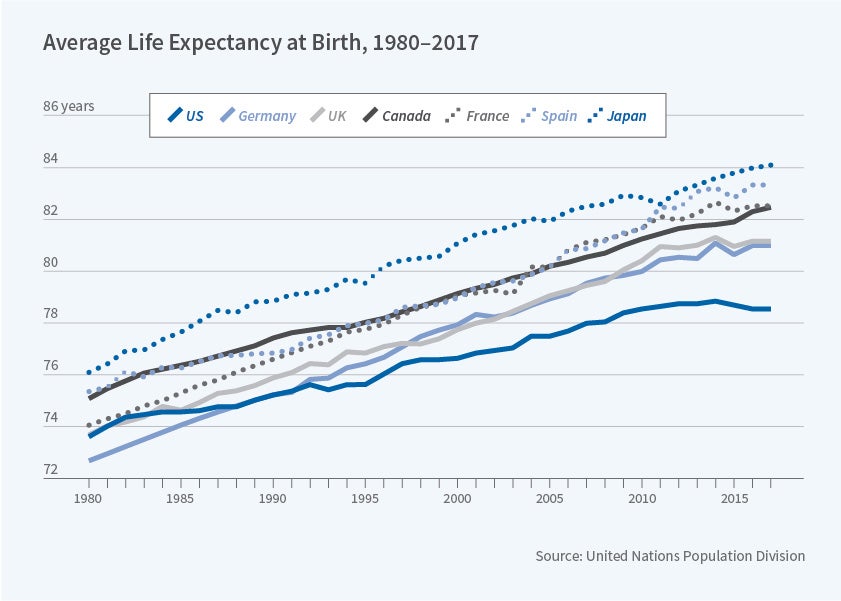

Health outcomes haven't kept up, as shown in Figure 2. US life expectancy was slightly below the average of comparable countries in 1980. Today it has fallen far below that of these other countries, with life expectancy actually declining for the first time in decades.

These striking facts have motivated a sharp increase in the quality and quantity of work in the NBER Health Care Program. From a handful of working papers in 1992, this program has grown to produce an average of more than 100 working papers a year in the last three full years. These papers reflect the larger interest of the economics profession in health issues. In 1990, the American Economic Review published just two articles about health; now it publishes about five a year. In the American Economic Journals in Economic Policy and Applied Economics, major new general-interest journals that cover health topics, about one in eight articles published in 2017 focused on health. The Health Care Program has expanded and drawn in a new generation of health economists.

In this review, I cover developments in the NBER Health Care Program over the last seven years. This has been a period both of substantial upheaval in the health-care sector and of rapid growth of studies of that sector, with 674 working papers posted in the program since 2012. These studies have covered a broad array of topics, and it is impossible to do them justice in this short review. Instead, I will highlight a few key areas of study by NBER researchers, with apologies to the large number of authors of studies that I am excluding.

The Affordable Care Act

The ACA is the most significant government intervention in the US health-care system since the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid. Moreover, it was introduced both in a data-rich environment in which many datasets can be used to analyze its impacts, and in a manner that generated quasi-experimental variation that can be used to convincingly estimate those impacts. In particular, the enormous expansion of the Medicaid program to all those whose income is less than 133 percent of the poverty line, which occurred only in a subset of states and over time in those states, provides a natural case study for understanding the impact of expanded insurance coverage. This has provided a wonderful environment for economic research.

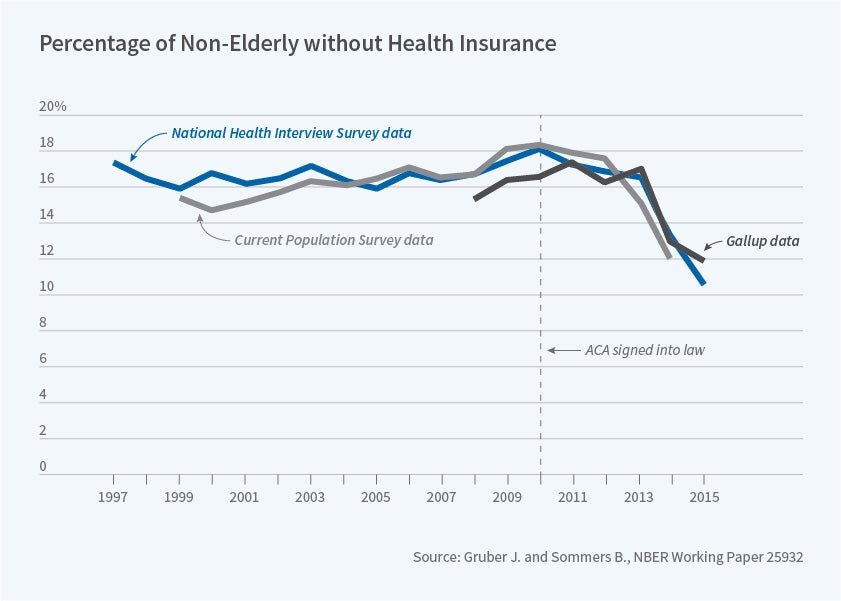

Health Care Program affiliates' research on the ACA has covered a wide variety of areas, but has focused primarily on the impacts of the ACA on insurance coverage, health-care utilization, and health, as reviewed by Benjamin Sommers and me.1 Studies show that the ACA clearly has expanded coverage [Figure 3] through provisions such as extending coverage of dependents up to age 26,2,3 expanding Medicaid,4 and subsidizing premiums in the new exchange.5 Notable is the finding of that last paper that much of the increase in Medicaid enrollment was not from those who were newly eligible, but from those previously eligible who had now enrolled in the program.

There has also been a clear increase in health-care utilization in response to broadened insurance coverage.6 Early studies have generally found positive impacts of the ACA on population health, but more work is needed to assess the long-term impacts on health.7 A particularly notable area of research on the ACA has been focused on the impact of the law's provisions on labor market behavior, with mixed results. Research on a large restriction on health insurance coverage in Tennessee before the ACA showed an associated significant rise in labor force participation, suggesting that expansions under the ACA might reduce the supply of labor.8 But studies of both the expansion of insurance to young adults 9 and the overall effects of the ACA exchanges and Medicaid exchanges10 do not find significant impacts on labor supply.

Physician Behavior

A common refrain in health economics is that the most expensive piece of medical technology is the physician's pen, yet there is relatively little understanding of the physician behaviors that drive medical spending. A set of recent papers has made enormous progress in helping us understand physician decision-making and its implications for the health-care system.

One of the enduring mysteries in health care is the enormous variation among physicians in treatment styles. These differences emerge in physician training.11 David Cutler, Jonathan Skinner, Ariel Dora Stern, and David Wennberg use surveys of physicians to show that much of the variation reflects physician beliefs unsupported by clinical evidence.12 There is mixed evidence on the welfare implications of physician treatment variation. Gautam Gowrisankaran, Keith Joiner, and Pierre-Thomas Léger find that physicians randomly assigned to different emergency department doctors who are more skilled see higher resource use, but not necessarily better outcomes.13 In contrast, Janet Currie, W. Bentley MacLeod, and Jessica Van Parys find that for heart attack patients, there is large variation in treatment intensity across providers, and those who treat more intensively deliver better outcomes.14

A related question is whether more information provided to patients can improve outcomes and performance. Jonathan Kolstad finds that when "report cards" were introduced on surgeon outcomes in Pennsylvania, surgeons responded strongly to poor performance relative to their peers, suggesting a strong role for "intrinsic motivation."15 At the same time, Erin Johnson and M. Marit Rehavi,16 and in another study, Michael Frakes, Anupam Jena, and I find that when physicians are themselves patients, they receive a quality of care similar to that of comparable non-physician patients.17

One recent development in health economics is an ongoing integration with the field of industrial organization, allowing for new lessons about physician (and other provider) market behavior. For example, Kate Ho and Ariel Pakes find that when physicians are more highly "capitated" (paid a fixed amount per patient, rather than receiving cost-based reimbursement), they are more likely to refer to lower-cost hospitals.18 Lawrence Baker, M. Kate Bundorf, and Daniel Kessler study the rapidly growing phenomenon of vertical integration among physicians, whereby generalists and specialists merge their practices; the researchers find that such integration raises prices for both types of physicians, particularly in less-competitive markets.19 Jeffrey Clemens and Joshua Gottlieb find that when private insurers set reimbursement rates for physicians, they closely follow the rates set by Medicare,20 although Clemens, Gottlieb, and Tímea Laura Molnár find that private rates deviate most from Medicare when the Medicare rate differs strongly from the true marginal cost of the procedure.21

Hospitals

Hospitals remain the largest single source of health-care spending, and this area continues to be a focus of NBER researchers. A number of studies have attempted to measure and compare the efficiency of care delivery across hospitals. Joseph Doyle, John Graves, Samuel Kleiner, and I have studied relative hospital treatment of emergency patients who are quasi-randomly assigned by preferences of different ambulance companies.22 Doyle, Graves, and I find that higher-cost hospitals deliver higher-quality care, that government measures of hospital quality are representative of true quality,23 and that a major source of inefficiency in health-care spending is variations across hospitals in their associated post-discharge spending.24 Paul Eliason, Paul Grieco, Ryan McDevitt, and James Roberts focus on the particular case of long-term acute care hospitals, showing that these hospitals strategically discharge patients when there is a large financial bonus for doing so, leading to worse patient outcomes.25 Liran Einav, Amy Finkelstein, and Neale Mahoney document that care received at these hospitals would have counterfactually been delivered at a much lower cost in other facilities, so that Medicare could save almost $5 billion per year by not allowing discharges to these providers.26

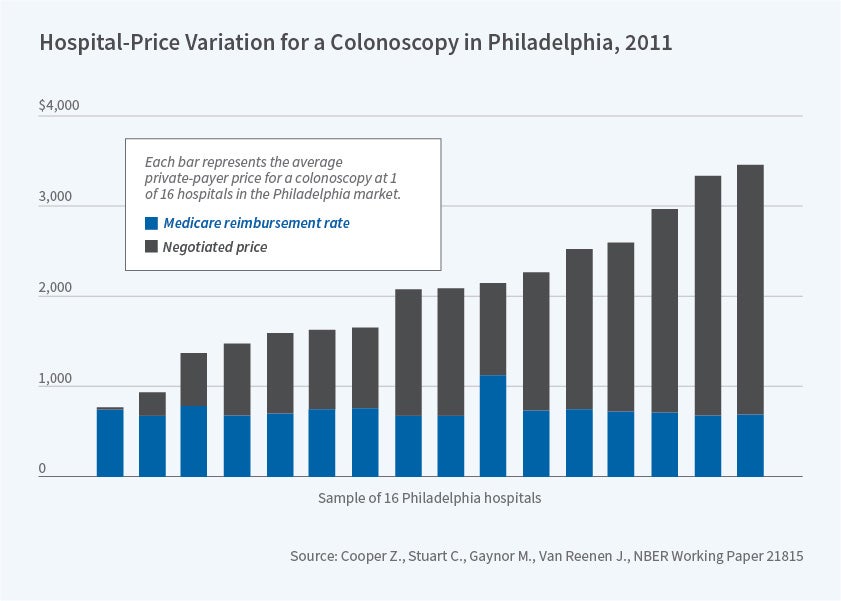

Another emerging topic of study is the role of hospital market structure. Motivating interest in this area is the widely cited study by Zack Cooper, Stuart Craig, Martin Gaynor, and John Van Reenen that used newly available data to document the enormous variation in prices among hospitals for very similar procedures; they also find that prices are higher in less competitive markets.27

Jill Horwitz, Charleen Hsuan, and Austin Nichols find that hospitals respond to a competitor's adoption of intensive cardiac services by adopting the same services, leading to duplication and higher costs.28 On the other hand, Gowrisankaran, Aviv Nevo, and Robert Town find that hospitals' market power is greatly constrained by their negotiations with managed care insurers,29 and Craig, Matthew Grennan, and Ashley Swanson find that mergers between hospitals lead to lower input acquisition prices through better negotiating power.30 Investigating another important aspect of hospital market structure, Cory Capps, Dennis Carlton, and Guy David find no evidence that nonprofit hospitals are more likely than for-profit hospitals to use the extra resources from market consolidation to deliver charity care to uninsured people.31

Pharmaceutical Economics

Prescription drug spending has become a larger share of health-care spending over the past few decades, growing from 5 percent of spending in 1980 to 10 percent today. This is partly due to the high cost of drug development, estimated at $2 billion or more annually. The enormous risk and returns associated with drug development have led to significant research on the determinants and outcomes of pharmaceutical R&D, and on the role of patent protection and generic competition in determining the long-run returns to these R&D investments.

Recent studies document that the financial resources available to pharmaceutical manufacturers determine the pace and nature of innovation, with somewhat differing conclusions. David Dranove, Craig Garthwaite, and Manuel Hermosilla find that the introduction of drug insurance for elderly people under Medicare Part D led to the development of more drugs targeted to the elderly — but mostly for diseases that already had multiple treatments.32 On the other hand, Joshua Krieger, Danielle Li, and Dimitris Papanikolaou find that financial shocks to pharmaceutical manufacturers lead to the development of drugs that are more novel, in the sense that they differ more from previous discoveries.33 In either case, the returns to R&D are quite high. Pierre Azoulay, Joshua Graff Zivin, Li, and Bhaven Sampat use idiosyncratic rigidities in the rules governing National Institutes of Health peer review to show that NIH funding spurs the development of private-sector patents: a $10 million boost in NIH funding leads to a net increase of 2.3 patents.34

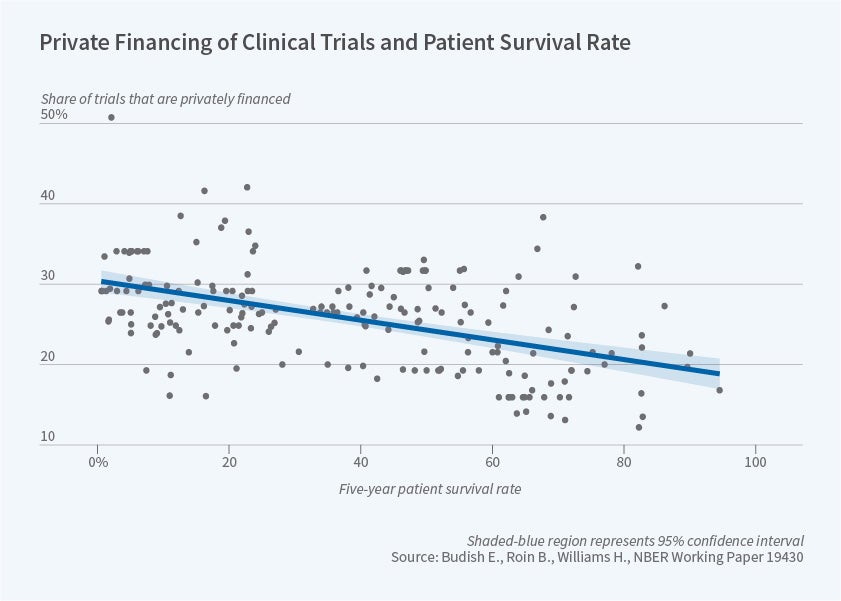

Heidi Williams and her coauthors have studied the incentives put in place by the US patent system. Sampat and Williams find that gene sequences that are patented are more valuable than those that are not, and that, controlling for this selection effect, on average, gene patents have no effect on follow-on innovation.35 At the same time, Eric Budish, Benjamin Roin, and Williams document that innovations with a long development period are less likely to be privately financed, since the patent protection provided when the drug is finally developed is very short-lived.36

Other studies have examined the generic drug market that results from the expiration of patent coverage — a market that has attracted much recent news coverage due to enormous price increases for some off-patent drugs. Consistent with these headlines, Ernst Berndt, Rena Conti, and Stephen Murphy survey the market for generic drugs and find a limited number of competitors for many generics, decreasing the price reduction that can be expected after patent expiration.37 At the same time, both they and Richard Frank, Andrew Hicks, and Berndt find that overall generic drug prices are falling substantially over time.38 In one particularly important market segment, Conti and Berndt find that the prices of specialty drugs fell significantly after a generic entered the market.39

Health Insurance Markets

A particularly notable feature of US health-care markets is the relatively unregulated multi-payer system for financing care, and more than 100 working papers in the last six years focused on the health insurance market. In particular, the wide variety of health insurance choices facing consumers and firms raises at least two important questions.

The first is how well do consumers do in choosing their health insurance plan, given the complicated nature of this decision. Jason Abaluck and I document that individuals appear to make highly inconsistent choices of health insurance plans, that these choices don't get better with more experience,40 and that limiting choice sets can lead to improved choice outcomes.41 Saurabh Bhargava, George Loewenstein, and Justin Sydnor42 and Chenyuan Liu and Sydnor deliver particularly compelling evidence for choice inconsistencies by showing the pervasive nature of "dominated" choices in health insurance markets.43 Richard Domurat, Isaac Menashe, and Wesley Yin run a field experiment randomly providing reminders about insurance deadlines to consumers; they find that such reminders are particularly effective among the healthiest consumers.44

The second major issue with health insurance choice is the potential for adverse selection and the need for risk adjusters to offset this market failure. Several studies have documented how concerns over adverse selection drive insurer behavior, leading, for example, to higher premiums for small firms with sicker employees,45 or to lower plan generosity when Medicare enrollees could more easily move from plan to plan.46 A series of studies by Thomas McGuire and his co-authors explored the theoretical and empirical determinants of optimal risk adjustment, raising issues such as the combination of different forms of reinsurance and risk adjustment.47 A key issue that must be evaluated with these systems is insurer responses. For example, Michael Geruso and Timothy Layton show how insurers "upcode" their enrollees to qualify for higher-risk adjustment payments.48 Finally, Benjamin Handel, Kolstad, and Johannes Spinnewijn highlight the trade-off between choice inconsistencies and adverse selection, and the implications for insurance design.49

International Comparisons

There is a long-standing recognition that the United States is an outlier in terms of health-care spending relative to GDP. This suggests that our nation has much to learn from other countries, and an array of studies has brought key lessons to the fore.

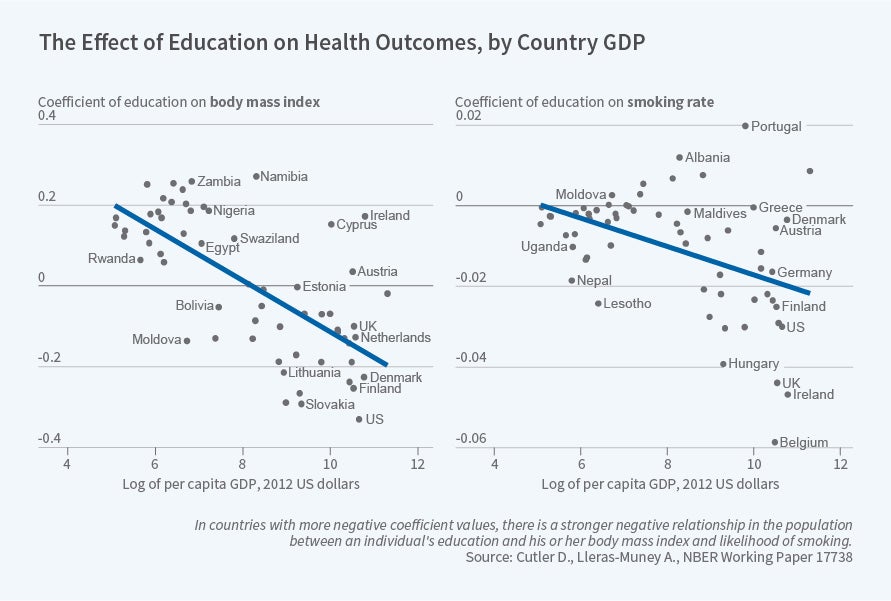

A number have focused explicitly on comparing the US to other nations. Cutler and Adriana Lleras-Muney review the evidence from around the world on how education improves health outcomes.50 Alice Chen, Emily Oster, and Williams provide evidence that the steep gradient in infant outcomes with respect to US income is largely driven by post-delivery differences in care, particularly care delivered in the home.51 Michael Baker, Currie, and Hannes Schwandt,52 and, in another study, Currie, Schwandt and Josellin Thuilliez compare mortality inequality in the US with that in Canada, where the inequality of health outcomes has declined, and France, where inequality remains pervasive.53 Jillian Chown, Dranove, Garthwaite, and Jordan Keener compare health care prices between the US and Canada, finding that while the US pays much more for drugs, our physicians do not appear to earn more relative to the general skill differential in pay in the US versus Canada.54

Other papers investigate policy interventions in other developed nations that may contain lessons for the US. Thomas Hoe, George Stoye, and I investigate a UK policy that imposes strict penalties on emergency rooms for long waiting times.55 We find that these incentives lead not only to shorter waiting times, with more use of the hospital and higher medical spending, but also to better health outcomes. [Figure 6] Hitoshi Shigeoka finds that reduced cost-sharing for elderly people in Japan leads to more use of both inpatient and outpatient care, with little impact on health but large reductions in out-of-pocket expenditures.56 Stephen Pichler and Nicholas Ziebarth use data from Germany and the US to document the importance of "presenteeism," whereby sick employees coming to work leads to more lost time for others, suggesting the value of providing sick leave to workers.57

A notable recent development is the rapid growth of work by Health Care Program affiliates on developing countries, likely motivated by synergies with NBER's Development Economics Program. Topics vary from the benefits of universal health care provision in Turkey,58 to investigations of adult mortality after a tsunami in the Indian Ocean,59 to experimental evidence on the promotion of iron-fortified salt in rural India,60 to audit studies illustrating the poor quality of primary health care in India,61 to the impact of a tobacco control campaign in Uruguay.

Where to Next?

The studies summarized here only begin to describe the enormous scope of work that has been undertaken by affiliates of the NBER's Health Care Program over the past seven years. These researchers are pushing the boundaries of knowledge in a wide variety of directions, and their efforts are likely to continue in the coming years. The ongoing implementation of the ACA provides a fruitful laboratory for studies of the role of insurance, while the continual threat of unaffordable increases in health-care costs will inspire new work on drivers of spending. The introduction of innovative new genetic therapies will motivate ongoing work on R&D and the financing of novel treatments. The increasing depth and diversity of new data sources, in the US and around the world, makes ever more exciting research feasible.

Endnotes

"The Affordable Care Act's Effects on Patients, Providers and the Economy: What We've Learned So Far," Gruber J, Sommers B. NBER Working Paper 25932, June 2019.

Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate," Antwi Y, Moriya A, Simon K. NBER Working Paper 18200, June 2012.

"The Role of Federal and State Dependent Coverage Eligibility Policies on the Health Insurance Status of Young Adults," Cantor J, Monheit A, DeLia D, Lloyd K. NBER Working Paper 18254, July 2012.

"Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage in Medicaid Expansion and Non-Expansion States," Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. NBER Working Paper 22182, April 2016.

"Premium Subsidies, the Mandate, and Medicaid Expansion: Coverage Effects of the Affordable Care Act," Frean M, Gruber J, Sommers B. NBER Working Paper 22213, December 2016.

"Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Mandate," Antwi Y, Moriya A, Simon K. NBER Working Paper 18200, June 2012; "The Effect of Insurance Expansions on Smoking Cessation Medication Prescriptions: Evidence from ACA Medicaid Expansion," Maclean J, Pesko M, Hill S. NBER Working Paper 23450, May 2017; "The Effect of Public Insurance Expansions on Substance Use Disorder Treatment: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act," Maclean J, Saloner B. NBER Working Paper 23342, April 2017; "Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Health Behaviors after Three Years," Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. NBER Working Paper 24511, April 2018.

"Early Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Health Care Access, Risky Health Behaviors, and Self-Assessed Health," Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. NBER Working Paper 23269, March 2017; "Impacts of the Affordable Care Act Dependent Coverage Provision on Health-Related Outcomes of Young Adults," Barbaresco S, Courtemanche C, Qi Y. NBER Working Paper 20148, May 2014.

"Public Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Employment Lock," Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo M. NBER Working Paper 19220, July 2013.

"The Impact of the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Provision on Childbearing, Marriage, and Tax Filing Behavior: Evidence from Tax Data," Heim B, Luri I, Simon K. NBER Working Paper 23092, January 2017.

"The Effects of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage and Labor Market Outcomes," Duggan M, Goda G, Jackson E. NBER Working Paper 23607, July 2017.

"Informational Frictions and Practice Variation: Evidence from Physicians in Training," Chan D. NBER Working Paper 21855, January 2016.

"Physician Beliefs and Patient Preferences: A New Look at Regional Variation in Health Care Spending," Cutler D, Skinner J, Stern A, Wennberg D. NBER Working Paper 19320, August 2013.

"Physician Practice Style and Healthcare Costs: Evidence from Emergency Departments," Gowrisankaran G, Joiner K, Léger P. NBER Working Paper 24155, December 2017.

"Physician Practice Style and Patient Health Outcomes: The Case of Heart Attacks," Currie J, MacLeod W, Van Parys J. NBER Working Paper 21218, May 2015.

"Information and Quality when Motivation is Intrinsic: Evidence from Surgeon Report Cards," Kolstad J. NBER Working Paper 18804, February 2013.

"Physicians Treating Physicians: Information and Incentives in Childbirth," Johnson E, Rehavi M. NBER Working Paper 19242, July 2013.

"Is Great Information Good Enough? Evidence from Physicians as Patients," Frakes M, Gruber J, Jena A. NBER Working Paper 26038, July 2019.

"Hospital Choices, Hospital Prices and Financial Incentives to Physicians," Ho K, Pakes A. NBER Working Paper 19333, March 2014.

"Does Multispecialty Practice Enhance Physician Market Power?" Baker L, Bundorf M, Kessler D. NBER Working Paper 23871, September 2017.

"In the Shadow of a Giant: Medicare's Influence on Private Physician Payments," Clemens J, Gottlieb J. NBER Working Paper 19503, October 2013.

"The Anatomy of Physician Payments: Contracting Subject to Complexity," Clemens J, Gottlieb J, Molnár T. NBER Working Paper 21642, October 2015.

"Do High-Cost Hospitals Deliver Better Care? Evidence from Ambulance Referral Patterns," Doyle J, Graves J, Gruber J, Kleiner S. NBER Working Paper 17936, March 2012.

"Evaluating Measures of Hospital Quality," Doyle J, Graves J, Gruber J. NBER Working Paper 23166, February 2017.

"Uncovering Waste in US Healthcare," Doyle J, Graves J, Gruber J. NBER Working Paper 21050, March 2015.

"Strategic Patient Discharge: The Case of Long-Term Care Hospitals," Eliason P, Grieco P, McDevitt R, Roberts J. NBER Working Paper 22598, September 2016.

"Long-Term Care Hospitals: A Case Study in Waste," Einav L, Finkelstein A, Mahoney N. NBER Working Paper 24946, August 2018.

"The Price Ain't Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured," Cooper Z, Craig S, Gaynor M, Van Reenen J. NBER Working Paper 21815, December 2015.

"The Role of Hospital and Market Characteristics in Invasive Cardiac Service Diffusion," Horwitz J, Hsuan C, Nichols A. NBER Working Paper 23530, June 2017.

"Mergers When Prices are Negotiated: Evidence from the Hospital Industry," Gowrisankaran G, Nevo A, Town R. NBER Working Paper 18875, March 2013.

"Mergers and Marginal Costs: New Evidence on Hospital Buyer Power," Craig S, Grennan M, Swanson A. NBER Working Paper 24926, August 2018.

"Antitrust Treatment of Nonprofits: Should Hospitals Receive Special Care?" Capps C, Carlton D, David G. NBER Working Paper 23131, February 2017.

"Pharmaceutical Profits and the Social Value of Innovation," Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Hermosilla M. NBER Working Paper 20212, June 2014.

"Missing Novelty in Drug Development," Krieger J, Li D, Papanikolaou D. NBER Working Paper 24595 May 2018.

"Public R&D Investments and Private-Sector Patenting: Evidence from NIH Funding Rules," Azoulay P, Graff Zivin J, Li D, Sampat B. NBER Working Paper 20889, January 2015.

"How Do Patents Affect Follow-On Innovation? Evidence from the Human Genome," Sampat B, Williams H. NBER Working Paper 21666, October 2015.

"Do Firms Underinvest in Long-Term Research? Evidence from Cancer Clinical Trials," Budish E, Roin B, Williams H. NBER Working Paper 19430, September 2013.

"The Landscape of US Generic Prescription Drug Markets, 2004–2016," Berndt E, Conti R, Murphy S. NBER Working Paper 23640, July 2017.

"The Price to Consumers of Generic Pharmaceuticals: Beyond the Headlines," Frank R, Hicks A, Berndt E. NBER Working Paper 26120, July 2019.

"Specialty Drug Prices and Utilization after Loss of US Patent Exclusivity, 2001–07," Conti R, Berndt E. NBER Working Paper 20016, March 2014.

"Evolving Choice Inconsistencies in Choice of Prescription Drug Insurance," Abaluck J, Gruber J. NBER Working Paper 19163, June 2013.

"Improving the Quality of Choices in Health Insurance Markets," Abaluck J, Gruber J. NBER Working Paper 22917, December 2016.

"Do Individuals Make Sensible Health Insurance Decisions? Evidence from a Menu with Dominated Options," Bhargava S, Loewenstein G, Sydnor J. NBER Working Paper 21160, May 2015.

"Dominated Options in Health Insurance Plans," Liu C, Sydnor J. NBER Working Paper 24392, March 2018.

"The Role of Behavioral Frictions in Health Insurance Marketplace Enrollment and Risk: Evidence from a Field Experiment," Domurat R, Menashe I, Yin W. NBER Working Paper 26153, August 2019.

"Reclassification Risk in the Small Group Health Insurance Market," Fleitas S, Gowrisankaran G, Lo Sasso A. NBER Working Paper 24663, May 2018.

"Insurers' Response to Selection Risk: Evidence from Medicare Enrollment Reforms" Decarolis F, Guglielmo A. NBER Working Paper 22876, December 2016.

"Reinsurance, Repayments, and Risk Adjustment in Individual Health Insurance: Germany, The Netherlands, and the US Marketplaces," McGuire T, Schillo S, van Kleef R. NBER Working Paper 25374, December 2018; "Assessing Incentives for Adverse Selection in Health Plan Payment Systems," Layton T, Ellis R, McGuire T. NBER Working Paper 21531, September 2015; "Risk Corridors and Reinsurance in Health Insurance Marketplaces: Insurance for Insurers," Layton T, McGuire T, Sinaiko A. NBER Working Paper 20515, September 2014; "Tradeoffs in the Design of Health Plan Payment Systems: Fit, Power and Balance," Geruso M, McGuire T. NBER Working Paper 20359, July 2014.

"Upcoding: Evidence from Medicare on Squishy Risk Adjustment," Geruso M, Layton T. NBER Working Paper 21222, May 2015.

"Information Frictions and Adverse Selection: Policy Interventions in Health Insurance Markets," Handel B, Kolstad J, Spinnewijn J. NBER Working Paper 21759, November 2015.

"Education and Health: Insights from International Comparisons," Cutler D, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 17738, January 2012.

"Why is Infant Mortality Higher in the US than in Europe?" Chen A, Oster E, Williams H. NBER Working Paper 20525, September 2014.

"Mortality Inequality in Canada and the US: Divergent or Convergent Trends?" Baker M, Currie J, Schwandt H. NBER Working Paper 23514, June 2017.

"Pauvreté, Egalité, Mortalité: Mortality (In)equality in France and the United States," Currie J, Schwandt H, Thuilliez J. NBER Working Paper 24623, May 2018.

"The Opportunities and Limitations of Monopsony Power in Healthcare: Evidence from the United States and Canada," Chown J, Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Keener J. NBER Working Paper 26122, July 2019.

"Saving Lives by Tying Hands: The Unexpected Effects of Constraining Health Care Providers," Gruber J, Hoe T, Stoye G. NBER Working Paper 24445, March 2018.

"The Effect of Patient Cost Sharing on Utilization, Health, and Risk Protection," Shigeoka, H. NBER Working Paper 19726, December 2013.

"The Pros and Cons of Sick Pay Schemes: Testing for Contagious Presenteeism and Noncontagious Absenteeism Behavior," Pichler S, Ziebarth N. NBER Working Paper 22530, August 2016.

"The Value of Socialized Medicine: The Impact of Universal Primary Healthcare Provision on Mortality Rates in Turkey," Cesur R, Gunes P, Tekin E, Ulker A. NBER Working Paper 21510, August 2015.

"Adult Mortality Five Years after a Natural Disaster: Evidence from the Indian Ocean Tsunami," Ho J, Frankenberg E, Sumantri C, Thomas D. NBER Working Paper 22317, June 2016.

"Can Iron-Fortified Salt Control Anemia? Evidence from Two Experiments in Rural Bihar," Banerjee A, Barnhardt S, Duflo E. NBER Working Paper 22121, March 2016.

"Quality and Accountability in Health-Care Delivery: Audit-Study Evidence from Primary Care in India," Das J, Holla A, Mohpal A, Muralidharan K. NBER Working Paper 21405, July 2015.