Child Wellbeing: Understanding the Role of Social Investments

Introduction

Childhood, which we define as the period from birth to age 18, is widely recognized as a pivotal period for human development over the life course. During this stage of development, children’s bodies and brains grow and evolve, responding to their environment and experiences. Investments during childhood can persistently shape life course outcomes as this stage is characterized by “critical” developmental periods. If a developmental milestone is not met by a specific age, then the child may “miss out” as investments experienced in later stages are less effective and cannot “make up” for lost ground earlier in life. Moreover, many chronic health conditions emerge during childhood and early treatment can improve wellbeing in both the short and long run. For example, the onset of many major mental health and substance use disorders (MHSUD) occur during childhood. Given the high rates of MHSUD among children and costs associated with these conditions within the US, understanding how to address MHSUDs early in life could have sustained and meaningful long-term benefits for both the people experiencing these conditions and society. Moreover, educational accumulation begins during childhood: children who perform well in school and develop solid learning and social skills are well positioned to obtain additional education and secure good jobs in the future, while children who do not gain these capacities face disadvantage as they enter adulthood and beyond.

Given the importance of childhood, substantial attention within the policy and academic spheres, and the general public, is placed on improving outcomes for children. Policymakers have adopted legislation to support children through health and education programs, and researchers—both within economics and across a broad range of disciplines—study how these programs, and other forces, shape child development. Our research examines how insurance, healthcare, and education interact with child wellbeing. More specifically, in a series of studies we have explored the impact of 1) state-level social insurance programs, 2) healthcare supply—with particular focus on MHSUD treatment, and 3) educational inputs on measures of child wellbeing. This review summarizes key findings from our work.

Social Insurance

Social insurance programs are designed to protect individuals against risks. These programs are key components of the social safety net and can support child development through in-kind income transfers to families, health insurance access, and so forth. In this line of research, we have examined how two forms of social insurance—paid sick leave (PSL) and public and commercial health insurance—shape child outcomes.

The US, unlike most developed nations, lacks a federal PSL policy. States have adopted PSL mandates which require employers to provide employees with, on average, seven days of PSL per year. Leave can be used for health and healthcare for the employee and their dependents—including children. All state PSL mandates include “safe time” provisions which allow employees to use leave to reduce exposure to violence (e.g., filing police reports and attending court proceedings). A lack of PSL can create tension between the dual responsibilities of work and childcare for parents and mandated PSL can relax some of these conflicts. In several studies, we have examined the impact of state PSL mandates on children’s outcomes and our findings suggest that these programs are supporting parental investments in children, reducing children’s exposure to domestic violence and maltreatment, allowing families to better time childbirth, and improving access to mental healthcare among children.

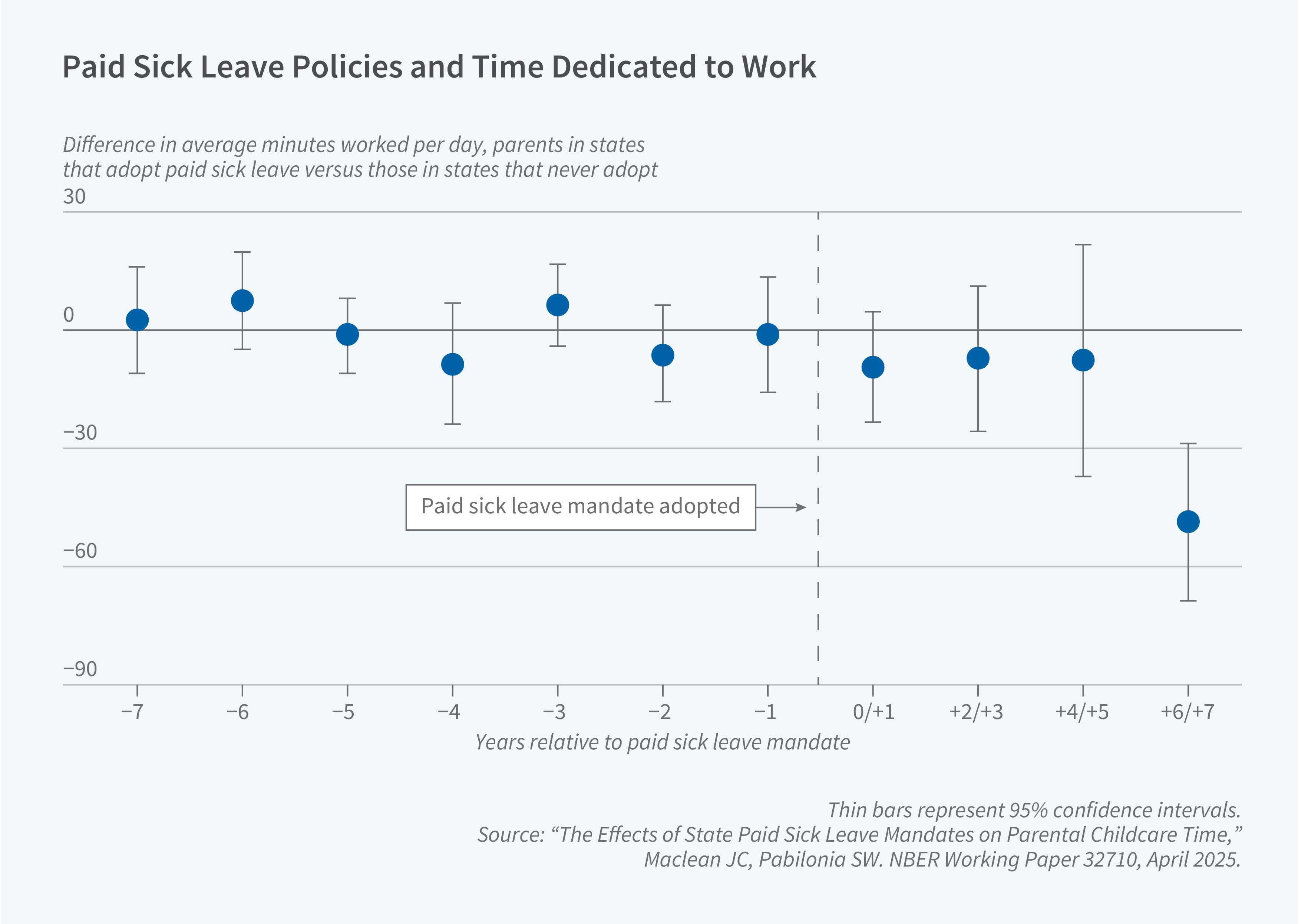

Using data from the American Time Use Survey, we show that parents with minor children in the household spend more time on childcare following a state PSL mandate.1 In particular, parents’ provision of primary care (e.g., bathing and feeding children) increases by 6 percent post-mandate, with effects being driven by women with younger children. Parents also increase their total time with children by 3 percent post-mandate. Analyzing administrative data on reports of maltreatment to Child Protective Services (CPS), we find that maltreatment reports decline by 8 percent following a state PSL mandate adoption.2 Mandated PSL leads to an increase in the probability of reporting one’s health as good, very good, or excellent by 1 percent, and a 7 percent decrease in the number of days with bad mental health among parents. Further, we show that intimate partner violence declines by 10 percent post-mandate. Thus, PSL mandates, potentially by improving parents’ health and their ability to execute their roles as caregivers, protect children from experiencing maltreatment, and these mandates may allow parents to leave unsafe domestic relationships that could expose children to maltreatment. While not a direct analysis of children, our study of the effects of PSL mandates on birth outcomes among women of childbearing age shows that, following mandate adoption, there is a 3 percent reduction in the birth rate.3 Our analysis of mechanisms suggests that PSL mandates allow women to use contraception and support employment among women. The ability to better time pregnancies, for example, delaying childbirth until the family has accumulated financial resources, and increase labor market earnings may allow parents to more optimally invest in their children.

Finally, we test the extent to which PSL mandates may alter patterns of mental healthcare utilization among children.4 We use all-payer health insurance claims data and our findings suggest that PSL mandates impact whether children use any mental healthcare and the type of care they receive. Following a PSL mandate, the probability that children use any mental healthcare increases by 8 percent. Interestingly, we find no evidence that the likelihood that an adult uses any mental healthcare varies with PSL mandates, which suggests that parents may prioritize their children’s use of healthcare when time costs are relaxed. Moreover, we document that increased time flexibility allows children to receive care that is more time-intensive: following mandate adoption, we find a decrease in prescription-medication-only treatment, the least time-intensive treatment option, and increases in both outpatient/inpatient care with and without medication, two more time-intensive treatment modalities. One interpretation of these findings is that, as time constraints are relaxed, parents are able to better match mental healthcare to their children’s specific treatment needs.

Medicaid—a public health insurance program for people with lower incomes and disabilities—is a vital source of health insurance for children in the US. We examine the extent to which Medicaid coverage influences children’s outcomes. We test the importance of Medicaid postpartum coverage for continuation of medications used to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD).5 Postpartum opioid use can be harmful to both the mother and the child. MOUDs—which are covered by most state Medicaid programs—are effective in reducing opioid use. However, until recently, Medicaid postpartum coverage ended after two months, creating a cliff in access to Medicaid generally and MOUD specifically for postpartum women. Beginning in 2021, Medicaid postpartum coverage was extended to 12 months. Using all-payer IQVIA claims data, we show that extending Medicaid coverage from two to ten months increases MOUD continuity among postpartum women by 5 to 9 percent. In a related paper using administrative data on substance use disorder (SUD) treatment episodes, we document limited impacts of expansions of income eligibility for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) on children’s use of SUD treatment.6 CHIP is a complementary public insurance program to Medicaid for children in families with lower income levels. Difficulty in accessing specialist SUD care among those covered by public insurance may limit the impact of these expansions. We find that state laws requiring coverage for SUD services in commercial insurance plans increase children’s use of SUD care by 26 percent, perhaps through spillovers on public insurance programs.

Healthcare Supply and Education

In a series of related studies, we examine how increasing the supply of MHSUD treatment providers influences children’s MHSUD outcomes and involvement with violence — both as offenders as well as victims. Features of MHSUDs such as impaired decision-making or attention can increase the risk of both crime commission and victimization. Treatment for MHSUDs is, on average, effective, but there are long-standing and well-established shortages of MHSUD providers within the US healthcare system. For example, according to government data, nearly 50 percent of people reside in mental healthcare shortage areas and just 20 percent of individuals with a SUD receive any related care each year. We examine how changes in the supply of MHSUD treatment influence child 1) deaths by suicide and by fatal drug overdose or alcohol poisoning, 2) arrest rates and associated social costs, and 3) maltreatment reports. We proxy changes in access to MHSUD treatment with fluctuations in the number of 1) office-based physicians (e.g., psychiatrists) and non-physicians (e.g., psychologists and social workers), and 2) residential and outpatient treatment centers specializing in MHSUD treatment within a county. These providers can treat most major MHSUDs with pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, inpatient care, "wraparound" services (e.g., educational programming), and other treatments.

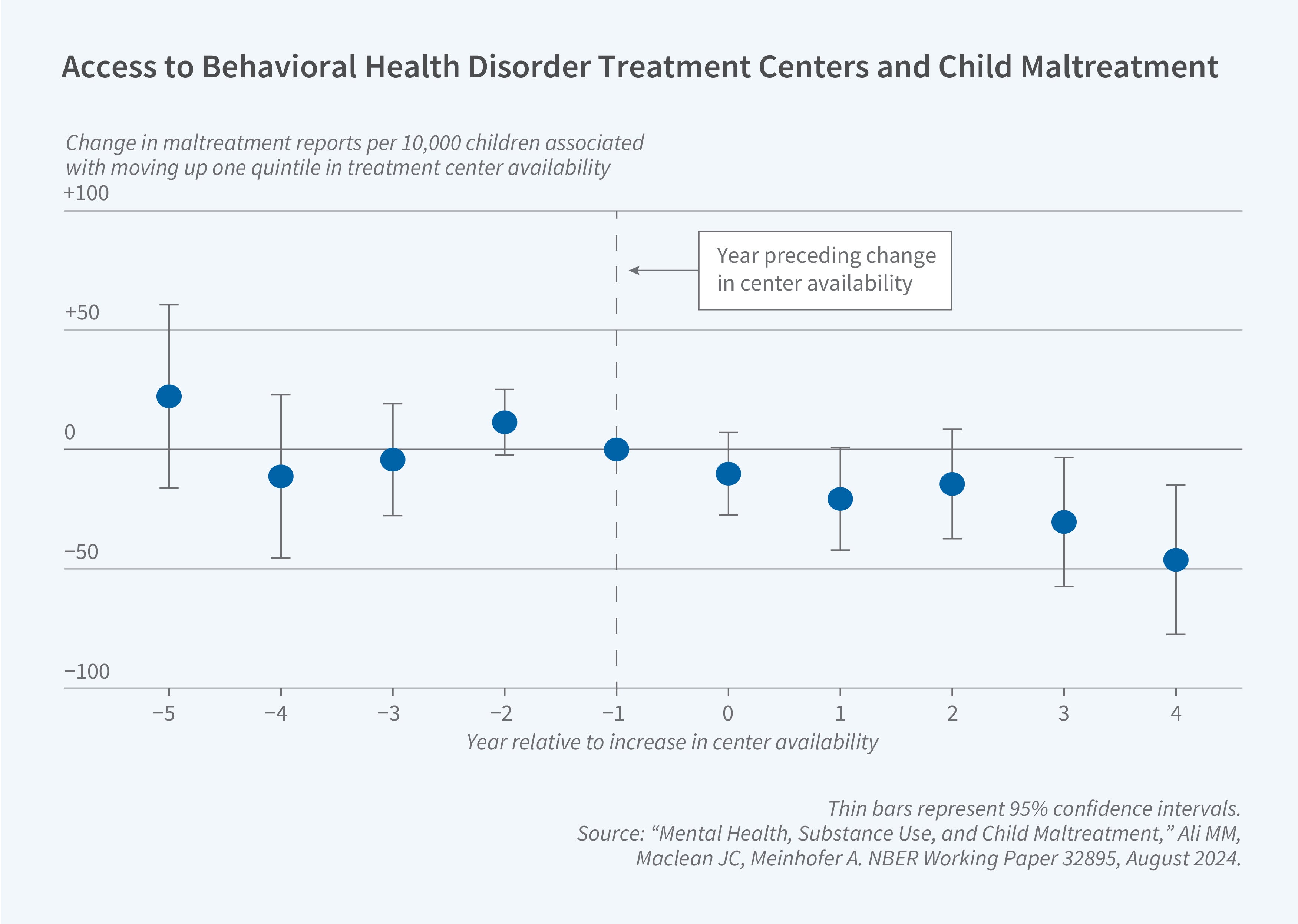

First, we show that increases in the number of MHSUD providers within a local market reduce deaths associated with MHSUDs among children. More specifically, a 10 percent increase in the number of office-based physicians and non-physicians reduces the suicide rate by 2 percent and a similarly sized increase in the number of residential and outpatient centers reduces the rate of deaths by suicide, fatal drug overdoses, and alcohol poisonings by less than 1 percent.7,8 Second, using FBI data, we find that a 10 percent increase in the number of offices of physicians and non-physicians specializing in MHSUD care in a county reduces child arrests by 1 percent, which results in a 5 percent reduction in the social cost of these arrests.9 A back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates that this change reflects an annual saving of $3,683 in crime costs per capita for the US. Third, using administrative data, we estimate that a 10 percent increase in the number of outpatient and residential centers reduces reports of child maltreatment to CPS by 1 percent.10 We show that improvements in management of both child and parent MHSUDs appear to be important mechanisms for this finding. In a follow-up paper, we further explore public safety and find that a 10 percent increase in the number of MHSUD providers leads to a 1 percent reduction in assaults on police officers.11 A strong public safety system could have beneficial effects for children.

We also examine how features of the school environment influence children’s wellbeing. Given that school-aged children spend a substantial amount of time in educational settings, understanding whether school characteristics impact children is important.12 We find that increasing the share of female peers in the school improves mental health among both boys and girls. We estimate that a 5 percentage point increase in the share of female peers at school decreases the propensity to meet the clinical threshold for depression among boys by 10 percent and among girls by 2 percent. Improvements in mental health are accompanied by stronger school friendships for boys and improved self-image for girls—these findings hint at the mechanisms between the observed peer relationships at school and mental health among children.

Summary

Taken together, our studies indicate that investments across a range of social programs including insurance, healthcare, and education can meaningfully improve child wellbeing. Our studies have primarily focused on the short-run effects of these programs. Given that childhood includes key developmental periods, the life course impacts could be even larger. Our research contributes to the literature that documents positive spillovers of public policies on child wellbeing.

Endnotes

“The Effects of State Paid Sick Leave Mandates on Parental Childcare Time” Maclean JC, Pabilonia SW. NBER Working Paper 32710, April 2025.

“Paid Sick Leave and Child Maltreatment” Deza M, Maclean JC, Ortega A. NBER Working Paper 33758, October 2025.

“Does Paid Sick Leave Facilitate Reproductive Choice?” Maclean JC, Ortega A, Popovici I, Ruhm CJ. NBER Working Paper 31801, September 2025.

“Time for Mental Healthcare: Evidence from Paid Sick Leave Mandates” Eisenberg M, Ge Y, Golberstein E, Maclean JC. NBER Working Paper 34254, September 2025.

“Medicaid Coverage and Postpartum Opioid Use Disorder Treatment” Gupta S, Ge Y, Maclean JC, Eisenberg MD. NBER Working Paper 34541, December 2025.

“Insurance Expansions and Children’s Use of Substance Use Disorder Treatment,” Hamersma S, Maclean JC. NBER Working Paper 24499, February 2020.

“Office-Based Mental Healthcare and Juvenile Arrests” Deza M, Lu T, Maclean JC. NBER Working Paper 29465, November 2021, and Health Economics 31(S2), August 2022, pp. 69–91.

“Mental Health, Substance Use, and Child Maltreatment” Ali MM, Lu T, Maclean JC, Meinhofer A. NBER Working Paper 32895, August 2024.

“Office-Based Mental Healthcare and Juvenile Arrests” Deza M, Lu T, Maclean JC. NBER Working Paper 29465, November 2021, and Health Economics 31(S2), August 2022, pp. 69–91.

“Mental Health, Substance Use, and Child Maltreatment” Ali MM, Lu T, Maclean JC, Meinhofer A. NBER Working Paper 32895, August 2024.

“Mental Health, Substance Use, and Child Maltreatment” Ali MM, Lu T, Maclean JC, Meinhofer A. NBER Working Paper 32895, August 2024.

“More Girls, Fewer Blues: Peer Gender Ratios and Adolescent Mental Health” Deza M, Zhu M. NBER Working Paper 34269, September 2025.