Organizational Approaches to Increased Worker Wellbeing and Productivity

Negotiations between workers and firm management are a defining feature of labor markets around the world. By many measures, labor relations have deteriorated substantially in recent years, often leading to strikes. In the United States, there were nearly 350 labor actions last year, the most in two decades, followed by 124 in the early months of 2024. Most of these actions are related to differences over worker compensation, benefits, and amenities.

Organizational economics is premised on the notion that firms are not monoliths but rather groups of individuals attempting to coordinate actions towards a set of common goals. Firm performance, then, depends critically on the preferences, incentives, and constraints of individuals, and the nature of their interaction within the organization. Understanding these many factors can help managers and workers create structures and policies that improve collective bargaining outcomes and, more generally, lead to improvements in both worker wellbeing and organizational productivity. Our work takes an organizational approach to understanding the impacts of increased investment in workers and improvements in firm capacity.

In the last decade, a dramatic increase in the availability of data on productivity and on the workplace behaviors of workers and managers has enabled much more granular study of the drivers of worker productivity across varying environments, as well as the rigorous empirical testing of seminal theories of interactions and relationships — both among workers and across the organizational hierarchy — that determine team performance. Our work over the last few years with various collaborators has leveraged rich administrative data and close partnerships with private sector firms across industries and contexts to contribute to this area of inquiry. We address the importance of the work environment for productivity, the targeting of managerial attention and effort, investments in training, managing worker expectations and potential disappointment, and the value of rapport in organizations.

The Work Environment

The degree to which workers feel comfortable in their work environment can contribute to their productivity. Our work with Namrata Kala combines daily production line-level data from Indian garment factories with weather data to estimate a negative, nonlinear productivity-temperature gradient.1 The impact on productivity can be seen starkly in the gradient between factory line-level productivity and the ambient temperature, with productivity sharply dropping off at precisely the human body’s heat stress threshold.

We establish that these conditions are malleable and can be controlled by the firm to influence worker performance. For example, we find that adopting energy-efficient LED lighting, which dissipates less heat on garment factory floors, raises productivity on hot days by dropping the ambient temperature in the factory below the body’s heat stress threshold. Such manipulation of the work environment can be surprisingly valuable to a firm. Using management’s cost data, we estimate that the payback period for LED adoption when accounting for productivity co-benefits is only one-third of the payback period that omits them. The average factory in our data gains about $2,880 in power consumption savings and about $7,500 in productivity gains from adopting LED lights.

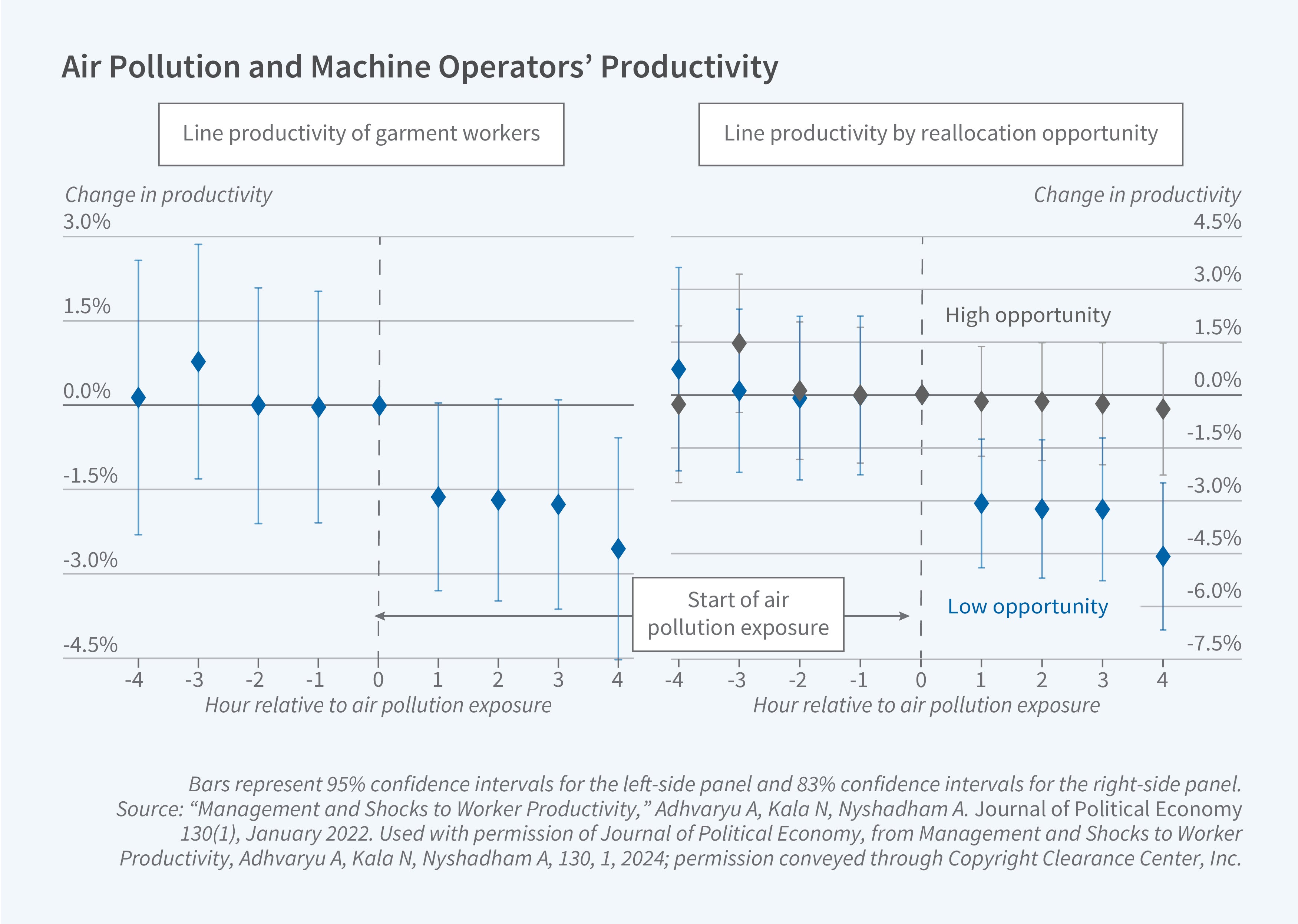

Air quality in the workplace can also impact productivity. Pairing productivity data from a garment firm with granular measures of air pollution, in another paper with Kala, we show that machine operator productivity in garment factories drops acutely when workers are exposed to above-average fine particulate matter concentrations in the air.2 We also show that if managers have enough workers who can be assigned to multiple operations, they can respond by reallocating particularly sensitive workers to improve worker-to-task matches, mitigating team productivity losses. However, whether and how well the manager can take advantage of these opportunities depends critically on how well the manager understands which workers are more resilient to this type of shock. We find that many managers do not devote the necessary level of attention to enable them to engage in high-impact worker-task reallocations.

Attention and Other Behavioral Determinants of Productivity

The importance of how managers allocate their attention can also be observed in the study of how quickly and effectively teams learn in the course of producing a given order. Combining granular garment production data with survey data on managers across 120 production lines in India, our work with Jorge Tamayo documents substantial productivity dispersion both across teams producing overlapping products and within individual teams over the course of production runs.3 We structurally link this variation to a comprehensive assessment of supervisor quality. We find that factors related to managerial attention and control — the latter being managers’ beliefs in their ability to affect outcomes rather than conceding outcomes to fate — are most important for enabling line productivity. While both dimensions affect all points along the productivity learning curve of the team, a manager’s sense of control is most important for starting orders at a higher initial productivity level, while attention most affects the rate of learning. Both managerial attention and control prove to be more impactful for determining productivity than traditionally emphasized dimensions like cognitive skills and tenure.

We find that technology can be leveraged to direct managerial attention and effort to the most impactful problems to solve. However, managers still must analyze the new information provided by the technology and choose their response strategies. In other work with Tamayo, we study the introduction of a technology that enabled managers to track the progress of drive-through orders in a large quick-service restaurant chain.4 Sales initially increased by five percent, driven by managerial training inputs, but the impact diminished by half within two months. Some managers invested in refreshing the training of workers at key workstations, while others provided new training for workers elsewhere in the store. The former “quality” strategy proved effective, yielding large and persistent sales improvements. The latter “quantity” strategy yielded modest initial sales gains that diminished over time despite continued investment. Our results highlight that even the gains from technological improvements depend fundamentally on human interaction with the technology.

Expectations and Disappointment

Workers have expectations and experience disappointment as well, and we find that even if employers understand the relationship between human comfort and productivity and decide to invest in improving working conditions, they must take care to set worker expectations appropriately or risk losing the benefits altogether.

Our work with Huayu Xu reports the impacts of a randomized housing quality improvement intervention among Indian migrant workers.5 Despite modest improvements in conditions, respondents experienced a decline in satisfaction and a large increase in psychological distress as a result of treatment. In contrast, residents who faced the same treatment-induced variation in living conditions as the original sample, but who arrived after treatment had already been initiated, had increased satisfaction. Impacts on turnover echo these patterns. We interpret this as evidence of reference dependence: Residents who were primed to expect larger-than-realized improvements in living conditions suffered utility losses, while exposed but unprimed residents experienced gains.

Similarly, when determining wage increases, employers can observe substantial disappointment depending on workers’ expectations ahead of the wage increase, but enabling worker voice in the aftermath can help to mitigate adverse consequences. In work with Teresa Molina, just after what proved to be a disappointing wage hike, we chose workers at random to participate in an anonymous survey in which they were asked for feedback on job conditions, supervisor performance, and overall job satisfaction.6 Enabling voice in this manner reduced turnover and absenteeism after the hike, particularly for the most disappointed workers. In a follow-up study with Smit Gade and Molina, we find that simply having access to a technology that enables voice can deliver effects of similar magnitudes on worker turnover and absenteeism even when actual utilization is low.7

Interactions and Relationships between Workers

In a series of studies, we document how the quality of interactions and relationships between workers can amplify or attenuate the impacts of these human conditions on performance at the team level. In work with Kala, we find that the skills required to effectively collaborate in teams are not uniformly present across workers, but that workers can be trained in these skills.8 The value of training workers in these types of soft skills can be surprisingly high, even when the tasks workers perform seem inherently independent, such as operating a machine. We estimate productivity gains of 13.5 percent from randomized on-the-job soft skills training among machine operators in Indian garment factories, but these productivity gains are most pronounced when trainees work on joint operations alongside other coworkers, particularly coworkers who also were trained. Furthermore, productivity is mirrored among nontreated coworkers on the production line, consistent with gains being driven by improved teamwork and collaboration. Heterogeneous treatment effects indicate that improvements in the teamwork and collaboration skills of workers substitute for supervisor attention, but that the training is complemented by the degree to which supervisors act autonomously to adjust production processes in response to issues raised by workers.

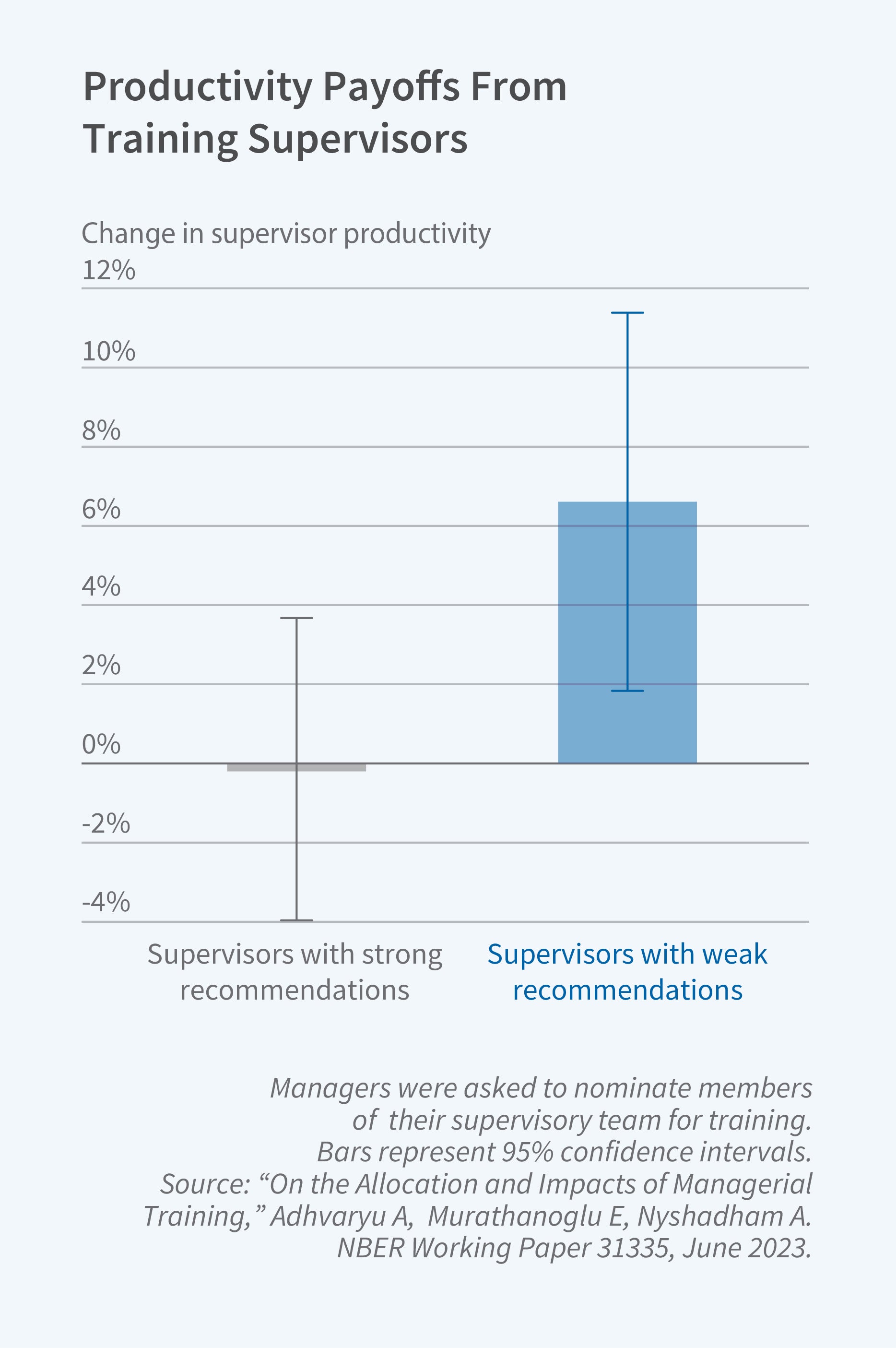

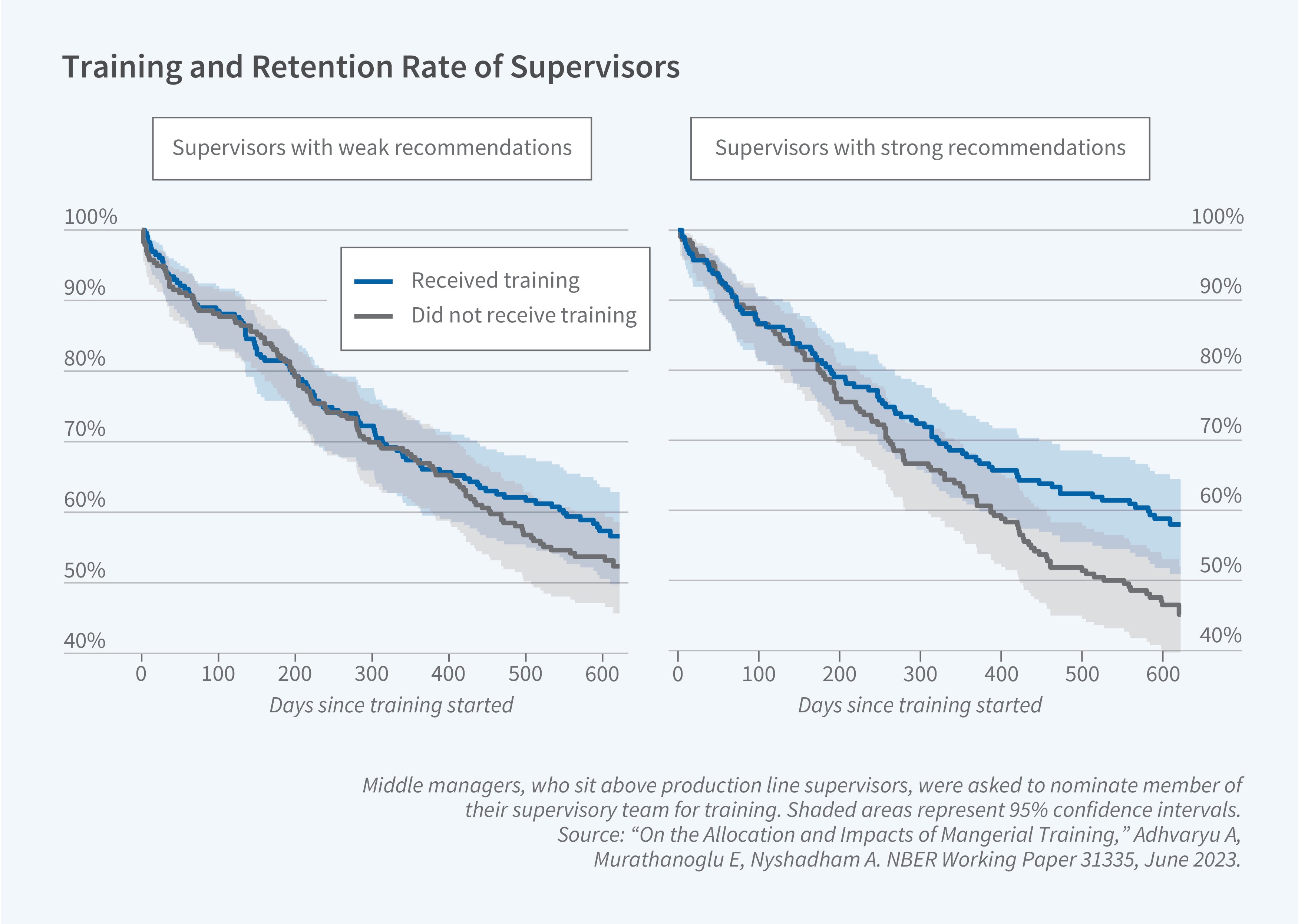

In work in a similar context with Emir Murathanoglu, we test whether investments in training supervisors in more-autonomous problem-solving and decision-making and more attentive monitoring of and communication with workers can have productivity impacts as well.9 While this training improved both manager knowledge of effective practices and the productivity of the teams they manage, the potential for human intervention — or in this case disruption — once again appears. Consistent with standard practice for training investments within firms, prior to the training assignment we asked middle managers, who sit above production line supervisors in the hierarchy, to nominate members of their supervisory team for training. Program access was randomized within these recommendation rankings. Highly recommended supervisors experienced no productivity gains while less recommended supervisors’ productivity increased by 12 percent relative to controls.

This was not due to poor information or favoritism. Instead, consistent with the fact that supervisor turnover comes at a large effort cost to middle managers due to gaps in coverage and onboarding, middle managers prioritized retention over productivity impacts. Indeed, treated supervisors were 15 percent less likely to quit than controls, a gain that was most pronounced for highly recommended supervisors. This scope for misalignment of incentives across the hierarchy in organizations and the misallocation of investments such as supervisor training can help explain the persistence of low managerial quality in firms, particularly in the developing world.

While the aforementioned study documents ways in which the hierarchy can hinder organizations’ productivity, there are many ways in which hierarchical structure can help allocate tasks within organizations efficiently. Seminal theories of how knowledge should be distributed across the hierarchy have existed for decades, but empirical evidence of how organizations might endogenously change their shape as objectives change has been hard to come by. In recent work with Vittorio Bassi, Nicolas Torres, and Tamayo, we use daily administrative data from a leading automobile manufacturer to study the organizational impacts of introducing greater task complexity in the form of new models in the auto assembly line.10 We first show that costly defects per vehicle spike when new models are introduced. As a response, the firm trains lower- and mid-level employees in problem-solving skills and encourages workers at these levels to solve the more complex problems that arise. In this sense, the organization takes on a less pyramidal shape in their knowledge hierarchy with fewer layers and a smaller span of control at each managerial level.

This rigorous empirical evidence, made possible by access to granular high-frequency personnel data on team structures, highlights the need for an extension to the classic theory of knowledge-based hierarchies. We develop such an extension that reconciles our novel empirical results by allowing the firm to invest in its training resources in a dynamic context in which product models become increasingly more complex at regular intervals, necessitating more knowledgeable, top-heavy teams, and the volume of production expands to take advantage of this greater stock of knowledge in the organization.

In a related study with Jean-François Gauthier and Tamayo, we document that peer managers of different teams in an organization can determine how well production issues can be addressed.11 For example, managers can borrow and lend resources, including workers, to cope with productivity shocks. One such shock which is ubiquitous is worker absenteeism. In the Indian garment manufacturing context, we document that worker absenteeism shocks are frequent, often large, and weakly correlated across teams, which substantially reduces team productivity. Together these facts imply gains from sharing workers. Accordingly, we study how relational contracts help managers cope with these worker absenteeism shocks.

Using unique data that tracks transfers of workers across teams, we show that managers respond to worker absenteeism shocks by lending and borrowing workers in a manner consistent with relational contracting, but many potentially beneficial transfers are unrealized because managers’ primary relationships are with a very small subset of potential partners. In this sense, we once again find that human tendencies determine how well this productive cooperation can be leveraged. Building trusting relationships is critical, as emphasized by seminal models of relational contracting. Physical distance on the factory floor and demographic differences — in age, gender, and education — can increase the costs of building this trust.

Trust is perhaps even more important in the worker-manager relationship. Workers and their managers interact each day and must cooperate in a myriad of ways to ensure smooth and productive operations. The rapport between the manager and worker can be a strong determinant of how well this cooperation can be achieved and team performance enhanced. In a study with Tamayo of the importance of rapport in organizations, we use personnel and productivity data from the universe of a large fast food chain in Colombia to study whether mismatched gender identity between managers and workers affects teams’ ability to deal with demand shocks.12 We leverage the staggered expansion across the country of a leading food delivery platform to study how well managers are able to adjust worker staffing to resulting increases in demand. In this setting, managers spend considerable time and attention on training workers and allocating them to shifts to meet variable demand. Worker cooperation is critical for the manager to successfully accomplish both of these tasks.

We show that stores in which managers and workers share predominantly the same gender have better communication and rapport between their managers and workers and more broadly skilled workers who are more easily reallocated across shifts. These stores exhibit the largest impacts on observed worker reallocation following the delivery platform implementation, and consequently, realize nearly three times the sales gains of stores in which predominantly male managers supervise predominantly female workers.

The scope for trust to drive productivity is apparent between organizations as well, and organizations may even tax productivity to invest in building and maintaining this trust. For example, in a recent study with Bassi and Tamayo, we leverage the high degree of worker mobility across production lines in a large Indian manufacturer and data on daily worker productivity to document that more-productive workers tend to be matched with less-productive managers.13 Estimates of the production technology, however, reveal that productivity would increase by up to 4 percent if the opposite pattern of worker-manager matching were implemented. Coupling these findings with a survey of managers and data on orders from multinational brands, we document that this forfeiting of productivity arises, at least in part, because maintaining valuable relationships with buyers provides strong incentives to avoid delays on orders by letting any given production line fall too far behind its targets. These results highlight how supply chain relationships shape production decisions at the firm level by affecting the internal organization of labor.

Low-Income Country Contexts

Much of our work on these topics has focused on firms operating in low-income country contexts. This perhaps reflects the greater potential in these contexts for improvements in physical environments, workers’ skills, managerial practices, and workplace relationships to increase productivity. Temperatures are hotter and air quality is poorer in these settings. Schools at all levels are less likely to prioritize professional and soft skills, and opportunities for internships and other experiences to develop these skills are fewer and more competitive. Managerial quality is lower even in the largest firms operating in global supply chains, and contracting is weaker with much more limited enforcement. In this sense, the opportunity to study these phenomena is greatest in low-income country contexts. But perhaps most importantly, the potential for impactful intervention to enhance the productive capacity and earning potential of workers is also greatest in these contexts. The studies highlighted here can hopefully serve as a springboard for future work in this area.

Endnotes

“The Light and the Heat: Productivity Co-benefits of Energy-Saving Technology,” Adhvaryu A, Kala N, Nyshadham A. NBER Working Paper 24314, February 2018, and The Review of Economics and Statistics 102(4), October 2020, pp. 779–792.

“Management and Shocks to Worker Productivity,” Adhvaryu A, Kala N, Nyshadham A. NBER Working Paper 25865, May 2019, and Journal of Political Economy 130(1), January 2022, pp. 1–47.

“Managerial Quality and Productivity Dynamics,” Adhvaryu A, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J. NBER Working Paper 25852, May 2019, and The Review of Economic Studies 90(4), July 2023, pp. 1569–1607.

“An Anatomy of Performance Monitoring,” Adhvaryu A, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 22-066, 2022.

“Hostel Takeover: Living Conditions, Reference Dependence, and the Well-being of Migrant Workers,” Adhvaryu A, Nyshadham A, Xu H. Journal of Public Economics 226, October 2023, Article 104949.

“Expectations, Wage Hikes, and Worker Voice: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” Adhvaryu A, Molina T, Nyshadham A. NBER Working Paper 25866, May 2019. Published as “Expectations, Wage Hikes, and Worker Voice” in The Economic Journal 132(645), January 2022, pp. 1978–1993.

“The Skills to Pay the Bills: Returns to On-the-Job Soft Skills Training,” Adhvaryu A, Kala N, Nyshadham A. NBER Working Paper 24313, February 2018. Published as “Returns to On-the-Job Soft Skills Training” in Journal of Political Economy 131(8), August 2023, pp. 2165–2208.

“On the Allocation and Impacts of Managerial Training,” Adhvaryu A, Murathanoglu M, Nyshadham A. NBER Working Paper 31335, June 2023.

“Organizational Responses to Product Cycles,” Adhvaryu A, Bassi V, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J, Torres N. NBER Working Paper 31582, August 2023.

“Absenteeism, Productivity, and Relational Contracts Inside the Firm,” Adhvaryu A, Gauthier J, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J. NBER Working Paper 29581, December 2021, and forthcoming in the Journal of the European Economic Association.

“Rapport in Organizations: Evidence from Fast Food,” Adhvaryu A, Howell P, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 24-032, 2023.

“No Line Left Behind: Assortative Matching Inside the Firm,” Adhvaryu A, Bassi V, Nyshadham A, Tamayo J. NBER Working Paper 27006, April 2020.