The Economics and Politics of Market Concentration

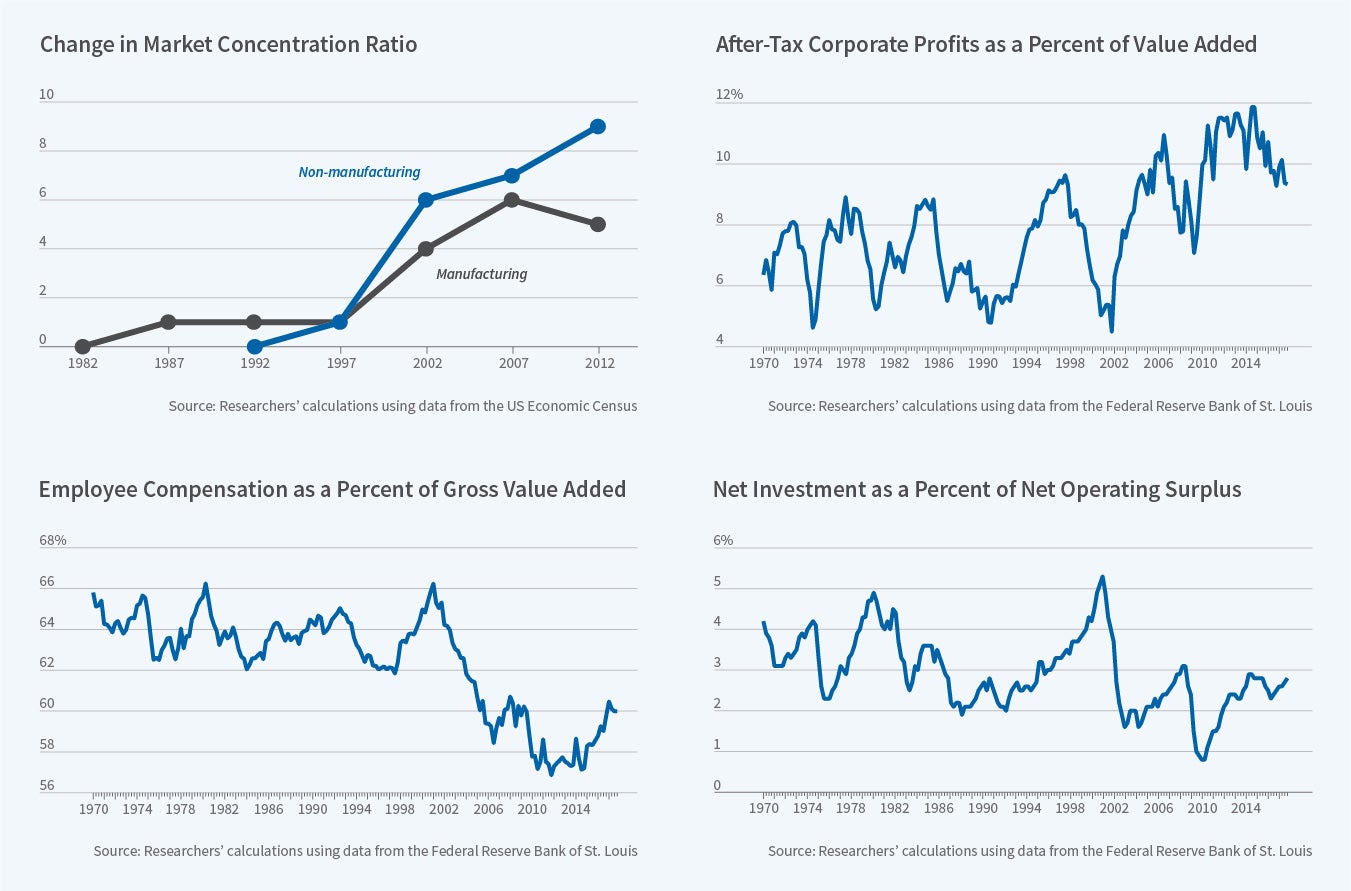

Business concentration and profit margins have increased across most industries in the United States over the past 20 years. Figure 1 illustrates these trends together with the declines of the labor share and private investment. The ratio of after-tax corporate profits to value added has risen from an average of 7 percent from 1970 through 2002 to an average of 10 percent in the period since 2002. Firms used to reinvest about 30 cents of each dollar of profit. Now they only invest 20 cents on the dollar.

Good versus Bad Concentration

A crucial research question is whether these trends reflect market power and rent seeking or more benign factors, such as a shift toward intangible assets with returns-to-scale effects. The main difficulty is that the relationship between concentration and competition is ambiguous.

Concentration and competition are positively related when shocks to ex post competition play a dominant role in the data. For example, lower search costs make it hard for inefficient producers to survive, force them to merge or exit, and lead to higher concentration. Increasing productivity differences among firms — often embedded in intangible assets — can play a similar role. If these explanations are correct, the remaining firms in the market should be the most productive and concentration should go hand in hand with strong productivity growth and intangible investment.

Concentration and competition are negatively related when shocks to entry costs play a dominant role in the data. This can result from changes in antitrust enforcement, barriers to entry, or the threat of predatory behavior by incumbents. If these explanations are correct, concentration should be negatively related to productivity and investment.

Some industries fit the efficient concentration hypothesis, while others fit the rent-seeking one. Ali Hortaçsu and Chad Syverson argue that the rise of superstores and e-commerce reflects efficiency gains in the retail industry.1 The wholesale trade sector also seems to fit this pattern. The telecom industry, on the other hand, fits the rent-seeking pattern rather well. It has become increasingly concentrated, and Germán Gutiérrez and I show that US consumers today pay twice as much for cell phone and broadband internet services as citizens in nearly all other developed countries.2 Some high-tech sectors combine features of the two types of concentration. One reason, as Nicolas Crouzet and Janice Eberly argue, is that intangible capital generates high returns and high rents at the same time.3

Over the past 20 years, however, negative concentration has become relatively more prevalent in the United States.4 Recent increases in concentration have been associated with weak productivity growth and declining investment rates. Firms in concentrating industries engage in more profitable mergers and acquisitions and spend more on lobbying.5 Excess profits are no longer competed away by free entry and the turnover of industry leaders has declined.6

The Political Economy of Concentration

If "bad" concentration has become prevalent, we need to understand why. What are the barriers to entry? What is the role of policy versus technology? It is difficult to obtain a convincing answer by looking only at the United States, but the comparison with other regions — Europe in particular — is quite illuminating. Until the 1990s, US markets were more competitive than European markets. Today, however, many European markets have lower excess profits and lower regulatory barriers to entry. Two US industries in particular exemplify the evolution of concentration and markups over time: telecoms and airlines.

Twenty years ago, access to the internet was cheaper in the US than in Europe. In 2018, however, the average monthly cost of fixed broadband in the US was twice as high as in France or Germany. Air transportation is another industry in which the US has fallen behind. The rise in concentration and profits aligns closely with a controversial merger wave that included the merging of Delta and Northwest in 2008, United and Continental in 2010, Southwest and AirTran in 2011, and American and US Airways in 2014. In Europe, over the same period, the growth of low-cost carriers has driven competition up and prices down.

European industries did not become cheaper and more competitive by chance. In all the cases that I have studied, there was a significant policy action, such as the removal of a barrier to entry or an antitrust action. The French telecom industry, for instance, was an oligopoly with three legacy carriers that lobbied hard to prevent entry. The oligopoly lost in 2011, a fourth operator obtained a license, and prices decreased by 50 percent within two years.

These results are surprising. Europe, with its tradition of protecting national champions, is not the place where we would have expected competition to thrive. The United States, with its tradition of free markets, is not the place where we would have expected competition to stall. How then can we explain these evolutions?

The theoretical explanation for Europe is actually relatively simple. When the institutions of the EU’s Single Market were designed in the early 1990s, there was significant suspicion among member states that each would try to impose its domestic agenda on the common regulators. Gutiérrez and I show that the Nash equilibrium of the regulatory-design game plays out differently at the national and EU levels.7 At the national level, politicians enjoy being able to influence regulators. At the EU level, however, they are mostly worried about influences from other countries. As a result, the member states jointly decided to make EU institutions more fiercely independent than they would have done at the national level. This is how Europe ended up with the most independent central bank as well as the most independent antitrust agency in the world. Over the following 20 years, the logic of the single market has slowly pushed Europe toward freer and more competitive markets.

Understanding how US markets became less competitive is more complicated. There are many possible explanations. Some concentration has been driven at least in part by increasing returns to intangible assets, as Crouzet and Eberly explain.8 The crucial test lies in the relationship between productivity growth and concentration. Matias Covarrubias, Gutiérrez, and I find a positive correlation between changes in concentration and productivity growth in the 1990s. This suggests that concentration was either benign or that it was the price to pay to achieve greater efficiency. The correlation became negative in the 2000s, however, suggesting a higher prevalence of rent seeking. Unfortunately, this is where the lack of data on firm-level prices and difficulties in making adjustments for labor quality create empirical challenges. There are also tricky econometric issues when we use granular data to test this relationship. A fair assessment is that we do not know for sure.

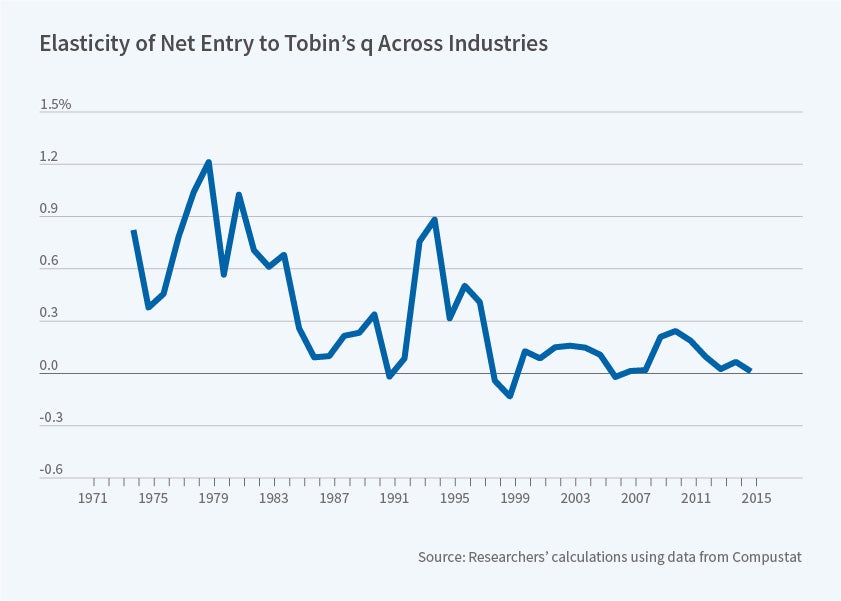

Two trends that are specific to the US in the 2000s help us to shed light on the issue. One is what Gutiérrez and I call the failure of free entry.9 When profits increase in an industry, new firms should enter. When profits shrink, existing firms should exit or consolidate. Economic theory predicts higher entry in industries with higher market-to-book values, also known as Tobin's q. Intuitively, Tobin's q measures expected profits (valued by the market) per unit of entry costs (book values). We study whether the number of firms increases in industries where Tobin's q is high and decreases in industries where it is low.

Figure 2 shows that free entry was alive and well from the 1960s to the late 1990s. The positive elasticity implies that, when the industry-median Tobin's q increased, more firms would enter the industry. Specifically, an increase in Tobin's q of one unit, as from 1 to 2, coincided with an increase in the number of firms in the industry of about 10 percent over the next two years. Consistent with free entry, firms used to enter into high q industries and exit from low q ones.

But this is no longer the case. The elasticity has been close to zero since 2000. A fundamental rebalancing mechanism that was at the heart of the Chicago School argument for not worrying about market dominance by a few large firms seems to have broken down. If free entry fails, the laissez-faire argument fails.

The other striking trend in the US during the 2000s is the rise in business lobbying and campaign finance contributions. Lobbying and regulation can explain the failure of free entry if incumbents use them to alter the playing field. Incumbents may, for example, influence antitrust and merger enforcement as well as regulations, ranging from the length and scope of patents and copyright protection to financial regulation, non-compete agreements, occupational licensing, and tax loopholes. Consistent with these ideas, we find that the elasticity of firm entry to Tobin's q has decreased more in industries that have experienced larger increases in lobbying and regulations.

The failure of free entry has negative implications for productivity, equality, and welfare in general. If capital gets stuck in declining industries and does not move to promising ones, the economy suffers: productivity growth is weak, wages stagnate, and standards of living fail to improve

Endnotes

"The Ongoing Evolution of US Retail: A Formal Tug of War," Hortaçsu A, Syverson C. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(4), 2015, pp. 89–112.

"How EU Markets Became More Competitive Than US Markets: A Study of Institutional Drift," Gutiérrez G, Philippon T. NBER Working Paper 02470, June 2019. See also: "Political Determinants of Competition in the Mobile Telecommunication Industry," Faccio M, Zingales L. CEPR. Discussion Papers, No. 11794, January 2017.

"Rents and Intangibles: A Q+ Framework," Crouzet N, Eberly J. Kellogg School of Management, Working Paper, October 2019.

The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets, Philippon T. Cambridge, MA; Harvard University Press, 2019.

"Are U.S. Industries Becoming More Concentrated?" Grullon G, Larkin Y, Michaely R. Forthcoming, Review of Finance.

"From Good to Bad Concentration? U.S. Industries Over the Past 30 Years," Covarrubias M, Gutiérrez G, Philippon T. NBER Working Paper 25983, September 2019.

"How EU Markets Became More Competitive Than US Markets: A Study of Institutional Drift," Gutiérrez G, Philippon T. NBER Working Paper 24700, June 2019.

"Rents and Intangibles: A Q+ Framework," Crouzet N, Eberly J. Kellogg School of Management, Working Paper, October 2019.

"The Failure of Free Entry," Gutiérrez G, Philippon T. NBER Working Paper 26001, June 2019.