Explaining Low Investment Spending

Declining product market competition and rising stock ownership by institutions can help explain falling corporate investment rates.

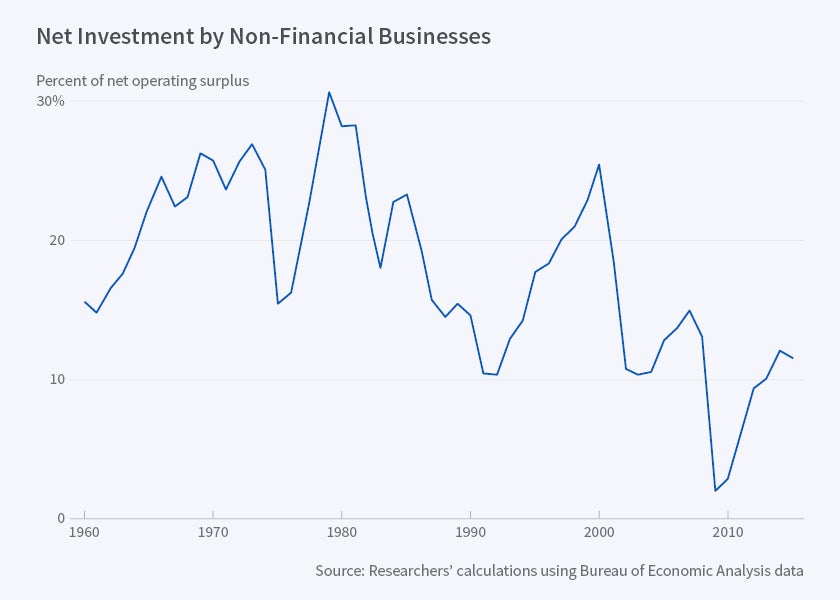

Private investment has been weak in recent decades, in contrast with past relationships between measures of profitability, company valuation, and investment spending.

In Investment-Less Growth: An Empirical Investigation (NBER Working Paper 22897), Germán Gutiérrez and Thomas Philippon examine the determinants of investment at both the industry and firm levels, with the goal of explaining the recent experience.

The researchers note that while investment averaged about 20 percent of corporate operating revenues between 1959 and 2001, it has averaged only 10 percent in the period 2002 to 2015. The low level of investment spending is inconsistent with explanations of investment that focus on the ratio of a company's market value, as measured by the value of its outstanding equity and debt, and the replacement cost of its assets. The late James Tobin first suggested the relationship between investment and this ratio, which is sometimes called "Tobin's Q." In recent years, Q has been high but investment has been low.

The researchers argue that this simple observation rules out a whole class of theories, including theories of increased risk aversion or decreases in expected growth. They then test eight alternative theories that they believe could explain the investment gap, including measures of financial frictions, measurement error (due to the rise of intangibles such as globalization), decreased competition, and tightened governance and/or increased short-termism. They conclude that 80 percent of the recent decline in investment can be explained by two factors: less competitive markets and increased ownership of stock by institutional investors. Imprecise measurement of intangible assets, such as goodwill, may account for some of the remainder.

The study measures competition by the number of firms in an industry and by sales and market value concentration. The researchers review data from the Census Bureau and corporate reports, and highlight several trends that suggest that competition may be decreasing in many economic sectors. These include a decades-long decline in new business formation and increases in industry-specific measures of concentration.

The researchers acknowledge that the relationship between competition and investment is complicated, but they argue that under a range of plausible assumptions, competition is likely to be positively associated with innovation and investment. Firms in concentrated industries, aging industries, and/or incumbents that do not face the threat of entry might have weak incentives to invest.

With regard to changes in the composition of share ownership, the researchers focus on quasi-indexers, which include institutions that have diversified holdings and low portfolio turnover. These investors currently account for 60 percent of institutional ownership, and their ownership share has grown significantly since 2000.

Why would ownership by quasi-indexers reduce investment? The researchers suggest that because quasi-indexers tend to be comparatively passive investors, the firms that they hold may be more vulnerable to the concerted efforts of activist investors. Executives may react to activists by focusing on short-term goals at the expense of a firm's long-term health, cutting back on investment to improve the bottom line or plowing profits into stock buybacks in the hope of boosting share price.

The study shows that firms with more quasi-indexer ownership do more buybacks. On the other hand, it finds no evidence that difficulty in obtaining financing accounts for lower investment rates. Firms with strong credit ratings—which would be expected to have continuing access to credit from both banks and the stock market—halved their investment from around 12 percent in the 1970s and 1980s to 6 percent after 2000.

The researchers caution that it is very difficult to establish causality between competition, stock ownership and governance, and investment, but they regard their findings as suggesting potential explanations for the recent experience.

—Steve Maas