Early Impacts of the Affordable Care Act

My recent research has focused on measuring the ways that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) affects the delivery of health services, labor market outcomes, and population health and well-being. Most of my work relies on quasi-experimental research designs that exploit differences in the ways states have implemented parts of the ACA, or ways that the law affects different sub-populations.

The ACA is a massive law that overhauls many parts of the U.S. health economy. The insurance expansions at the heart of the legislation only occurred in 2014, and studies of the early effects of these changes are only now starting to emerge. However, other aspects of the law came into play much earlier, and I have focused on those changes. In particular, my coauthors and I have examined the 2010 young-adult provision that requires private insurers to allow dependents to remain on their parents' policies until the age of 26 and have several interesting findings.

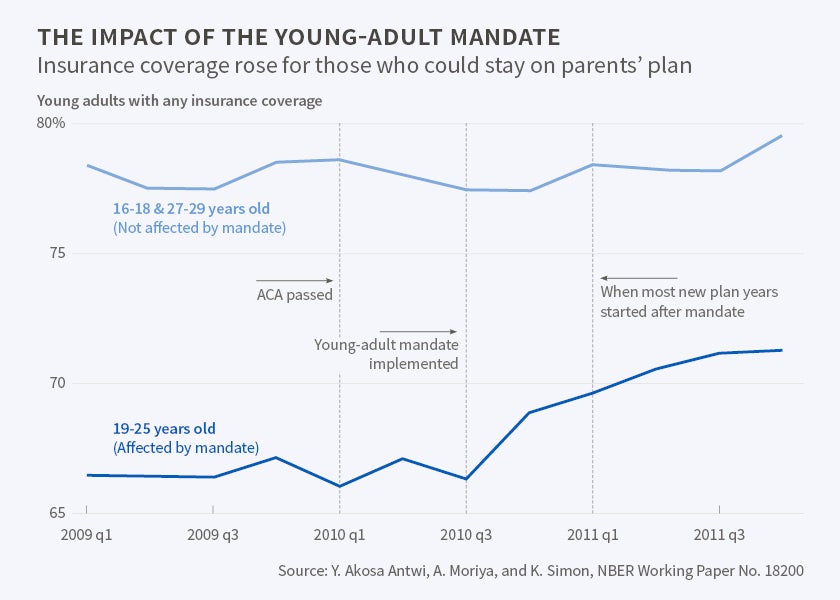

First, the effect of the law on young adults' insurance coverage was quite dramatic. Almost immediately, this provision increased parental employer coverage of young adults by more than 40 percent—slightly more than 2 million young adults. This expansion also altered health care utilization, increasing young adults' use of inpatient health care and slightly reducing emergency room use. So far, the young-adult expansion does not appear to have substantially affected labor market outcomes.1

My work on the young-adult expansion exploits a quasi-experimental research design. The key idea is that even though this provision was implemented nationally, it only affected 19- to 25-year-olds. To help control for time trends and other sources of bias, my colleagues and I compare the time series of outcomes among the 19- to 25-year-olds with the time series in a comparison group of young adults slightly outside that age range and therefore unaffected by the policy change. This approach rests on the assumption that, absent the policy change, the younger and older adults would have followed similar time trends in outcomes. For most outcomes, the assumption appears plausible based on pre-policy trends tests, and the age-based difference-in-difference comparison is now the standard approach in a sizable literature on the ACA young-adult provision.

Take Up and Crowd Out

In a series of papers with Yaa Akosa Antwi, Aaron Carroll, Bradley Heim, Ithai Lurie, Jie Ma, Asako S. Moriya, and Benjamin D. Sommers, I examine the impacts of the young-adult mandate using both survey and administrative data. In our first paper, we use household survey data to show that the provision proved popular, with parental employer-sponsored insurance among young adults rising quite dramatically from March 2010 to November 2011, leading to large reductions in the number of uninsured.2 [See Figure 1.] Our estimates suggest that the ACA reduced by about one third the number of uninsured among targeted individuals with parental offers of employer coverage. The high take-up rate of the newly available coverage may be surprising, given that young adults are a relatively healthy population with other spending priorities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the protective role of parents may have proved key to accounting for the impact of this particular provision.

Aside from take up, a pressing question in health insurance expansion has been the extent to which pre-existing forms of insurance are crowded out. We find that the increase in parental coverage drew almost equally from among the uninsured and the otherwise-insured populations. Prior research shows that substitution between different forms of coverage was present during the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) expansion. In the CHIP case, however, concern focused on whether public coverage displaced private coverage, whereas in the case of the young-adults reform associated with ACA, private parental coverage mostly displaced other sources of private coverage.3

Health Care Utilization

Even though young adults are not frequent users of health care generally, they are at greater risk than the general population of needing certain types of care, such as mental health care. We examine the effects of the young-adult expansion on use of care, using administrative hospital claims data,and find that use of inpatient hospital care increased 3.5 percent among young adults, with care for mental health-related illnesses rising 9.0 percent and emergency room (ER) use falling slightly. 4 The reduction in ER use occurred mainly for weekday admissions, suggesting that use of ambulatory care increased; unfortunately, while researchers have access to a great deal of all-payer data on hospital care, there are no rich sources of data available to directly study ambulatory or preventive care.

Maternity Care Coverage

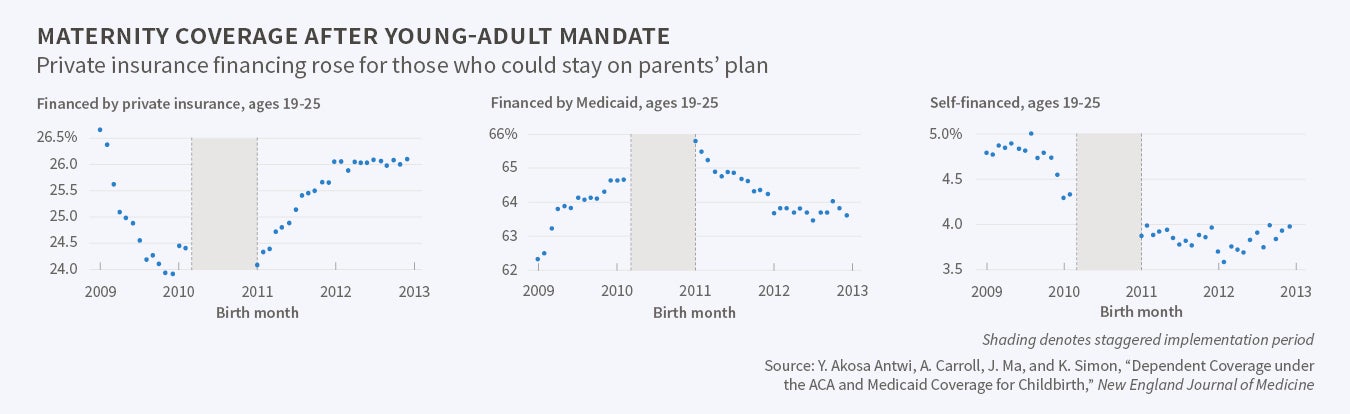

Following the insights that young adults are highly represented in certain patient populations, and that some degree of substitution among types of health insurance occurs in response to expansion, we examine impacts of the young-adult provision on use of maternity care. More than a third of all babies in the U.S. are born to women age 19 to 26. Although non-disabled young adults are generally ineligible for Medicaid coverage, pregnancy-related health insurance through Medicaid is an exception. Using birth certificate records that document source of payment for childbirth, we find evidence consistent with a reverse crowd-out effect, by which, following implementation of the young-adult provision, private insurance replaced Medicaid to a certain extent.5 Figure 2 shows that the percentage of births financed by private insurance increased following the staggered implementation of the young-adult mandate, while the percentage of births financed by Medicaid fell. These patterns are evident for the affected age group (19- to 25-year-olds), while no such clear pattern emerges for older mothers unaffected by the policy (27- to 29-year-olds).

This particular change in source of payment may be useful to exploit in the future to understand how generosity of insurance type affects access to providers, as this case represents a substitution of high-generosity insurance offered through parents' employers for low-generosity insurance (Medicaid).

Labor Market Effects

One of the unintended consequences of U.S. reliance on health insurance provided through employers is its potential to reduce workers' job mobility. The young-adult law provides an opportunity to test the job-lock hypothesis, using availability of health insurance through another family member. This method echoes an identification approach used in the previous literature that found substantial evidence of job lock in the early 1990s.6 We used rich administrative tax data to test the implications of the young-adult provision on labor market outcomes and related aspects of young-adult lives.7 These data have several advantages over survey data, as they contain information on non-resident parents' access to employer benefits which is not typically available in survey data. We detect no substantial changes in a large set of outcomes, including measures of employment status, job characteristics, and post-secondary education, even when restricting attention to young adults whose parents have access to employer benefits. These findings may be unsurprising given the relatively good health of this age group, implying a lack of salience of health insurance in their employment choices. In ongoing work with the same data, we examine the demographic consequences of the law, following prior work in which my coauthors and I investigated the relationships between health insurance and marriage and fertility.8 These administrative data present exciting opportunities for future research on the 2014 ACA expansions, particularly because the ACA mandates the collection of additional information on insurance coverage in tax data.

My most recent research explores early effects of the 2014 Medicaid expansion. Using the quasi-natural experiment created by a 2012 Supreme Court decision, following which about half the states opted out of the Medicaid expansion that would cover adults earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, my co-authors and I find no statistically detectable effects on labor market outcomes.9 While this is important early evidence, sharper study designs are needed to focus exclusively on those who are treated.

Future Directions in ACA Impact Studies

When the ACA passed in 2010, there was a great deal of ambiguity regarding how U.S. health policy would be redefined by the law. The years since have witnessed much uncertainty about the law's implementation. However, aside from the 2012 Supreme Court decision weakening the Medicaid expansion, the main ACA provisions took effect largely as planned. Taken as a package, the ACA has made vast changes to the regulation and financing of the health care sector, providing researchers with openings to explore many questions in health economics. In light of the prominent position of health reform in current public affairs, these opportunities for research will also produce evidence that informs the ongoing and deeply salient debates about the appropriate design of U.S. health care policy.

Endnotes

Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, and K. Simon, "Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Dependent-Coverage Mandate," NBER Working Paper 18200, June 2012, and American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4), 2013, pp.1–28; Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, and K. Simon, "Access to Health Insurance and the Use of Inpatient Medical Care: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Mandate," NBER Working Paper 20202, June 2014, and Journal of Health Economics, 39, 2015, pp.171–87; Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, K. Simon, and B. Sommers, "Changes in Emergency Department Use among Young Adults after the ACA's Dependent Coverage Provision," Annals of Emergency Medicine, 65(6), pp. 664–72; Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Carroll, J. Ma, and K. Simon, "Dependent Coverage under the ACA and Medicaid Coverage for Childbirth," New England Journal of Medicine, 374(2), 2016, pp. 194–6, Research Letter; and B. Heim, I. Lurie, and K. Simon, "The Impact of the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Provision on Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Tax Data," in J. Brown, ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol 29, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015, pp. 133–57.

Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, and K. Simon, "Effects of Federal Policy to Insure Young Adults: Evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Dependent-Coverage Mandate," NBER Working Paper 18200, June 2012 and American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4), 2013, pp.1–28.

J. Gruber and K. Simon. "Crowd-Out Ten Years Later: Have Recent Public Insurance Expansions Crowded Out Private Health Insurance?" NBER Working Paper 12858, January 2007, and Journal of Health Economics, 27(2), 2008, pp. 201–17.

Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, and K. Simon, "Access to Health Insurance and the Use of Inpatient Medical Care: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Mandate," NBER Working Paper 20202, June 2014, and Journal of Health Economics, 39, 2015, pp.171–87; Y. Akosa Antwi, A. Moriya, K. Simon, and B. Sommers, "Changes in Emergency Department Use among Young Adults after the ACA's Dependent Coverage Provision," Annals of Emergency Medicine, 65(6), 2015, pp. 664–72.

B. Madrian, "Employment-Based Health Insurance and Job Mobility: Is There Evidence of Job-Lock?" NBER Working Paper 4476, September 1993, and Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(1) 1994, pp. 27–54.

B. Heim, I. Lurie, and K. Simon, "The Impact of the Affordable Care Act Young Adult Provision on Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Tax Data," in J. Brown, ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol 29, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015, pp. 133–57.

E. Peters, K. Simon, and J. Taber, "Marital Disruption and Health Insurance," NBER Working Paper 20233, June 2014, and Demography, 51(4), 2014, pp. 1397–1421; and T. DeLeire, L. Lopoo, and K. Simon, "Medicaid Expansions and Fertility in the United States," NBER Working Paper 1290, February 2007, and Demography, 48(2), 2011, pp. 725–47.