Fiscal Policy in Emerging Markets: Procyclicality and Graduation

Five key questions have guided my research on fiscal policy in emerging markets:1

- How is fiscal policy conducted in emerging markets compared to industrial countries?

- Why has fiscal policy often been procyclical in emerging markets?

- Are there developing countries that have "graduated" — that is, switched from being procyclical to countercyclical?

- Has fiscal policy been an effective countercyclical tool?

- Is the recent experience of some eurozone countries reminiscent of past fiscal behavior in emerging markets?

This summary describes the main findings that have resulted from this research agenda. In pursuing these issues, I have been very fortunate to work with many talented co-authors, whose many contributions will hopefully become clear below.

Fiscal Policy in Emerging Countries: When It Rains, It Pours

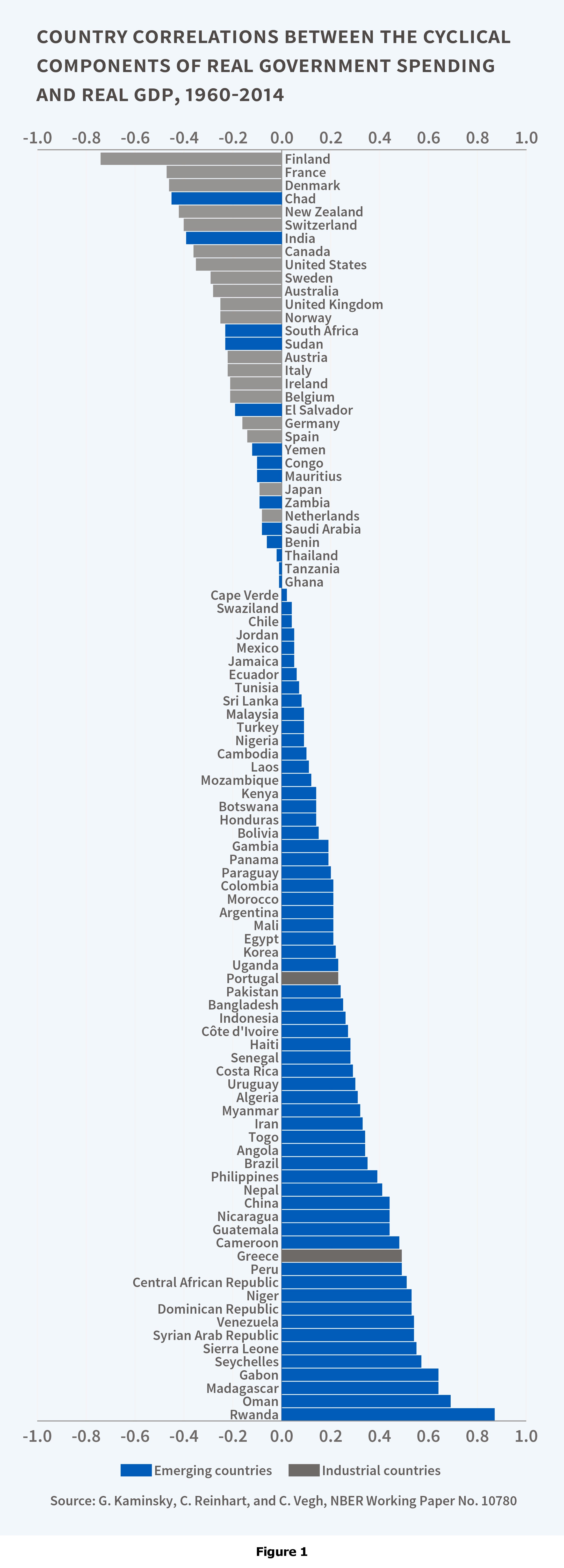

Figure 1, on the next page, shows the correlation between the cyclical components of real GDP and government spending for 96 countries (21 industrial and 75 developing) for the period 1960–2014.2 Industrial countries are denoted by gray bars while blue bars represent emerging countries.

The visual impression is striking: With only two exceptions, Greece and Portugal, all grey bars lie to the left of the graph, indicating a negative correlation and hence countercyclical government spending in industrial countries, while 81 percent of blue bars lie to the right of the graph, indicating a positive correlation and hence procyclical government spending in developing countries. In fact, the average correlation for industrial countries is -0.23, compared to 0.21 for developing countries. Both estimates are significantly different from zero at the one percent level.

Although much less documented — mainly because data on tax rates are much harder to come by — the same is true of tax policy. Based on a novel annual dataset that comprises value-added, corporate, and personal income taxes for 62 countries (20 industrial and 42 developing) for the period 1960–2013, Guillermo Vuletin and I have concluded that tax policy has been acyclical in industrial countries and mostly procyclical in developing economies.3 By procyclical tax policy, we mean that the correlation between the cyclical components of tax rates and GDP is negative; that is, it reinforces the business cycle.

The evidence thus strongly suggests that, unlike industrial countries, developing countries have historically pursued procyclical fiscal policy both on the spending and the revenue side. During bad times, with capital flowing out and the economy mired in recession, policymakers have often compounded the problem by contracting fiscal policy.

Why has Fiscal Policy been Procyclical in Emerging Markets?

A natural question is why policymakers in developing countries exacerbate already pronounced boom-bust cycles by pursuing procyclical fiscal policy. This has been a puzzle in search of an explanation. The two most convincing explanations are arguably that they have limited access to international credit markets in bad times, and that political incentives and institutional weaknesses tend to encourage "excessive" public spending in good times.4

These two channels have in fact reinforced one another in bringing about procyclical fiscal policy. Emerging countries' inability to borrow in bad times — often in conjunction with calls for "fiscal consolidation" from international creditors and organizations — has typically left them with little choice but to cut spending and raise taxes in the midst of severe recessions.

This situation has only been made worse by the tendency to save little, if any, during temporary booms fueled by surges in commodity prices and capital inflows. Time and again, policymakers have insisted that good times were here to stay and spent accordingly. Spending proceeds that are temporary in nature as though they were permanent naturally forces governments to contract spending and raise taxes in bad times to satisfy the intertemporal budget constraint (or, alternatively, default). Put differently, the textbook recommendation of saving on sunny days for rainy days has been seldom, if ever, followed in emerging markets.

Graduation

Fortunately, fiscal policy is not an immutable phenomenon and changes in market access and domestic financial institutions have enabled many developing countries over the last 15 years to switch from being procyclical to acyclical or even countercyclical, a phenomenon dubbed "graduation" in my work with Jeffrey Frankel and Vuletin.5

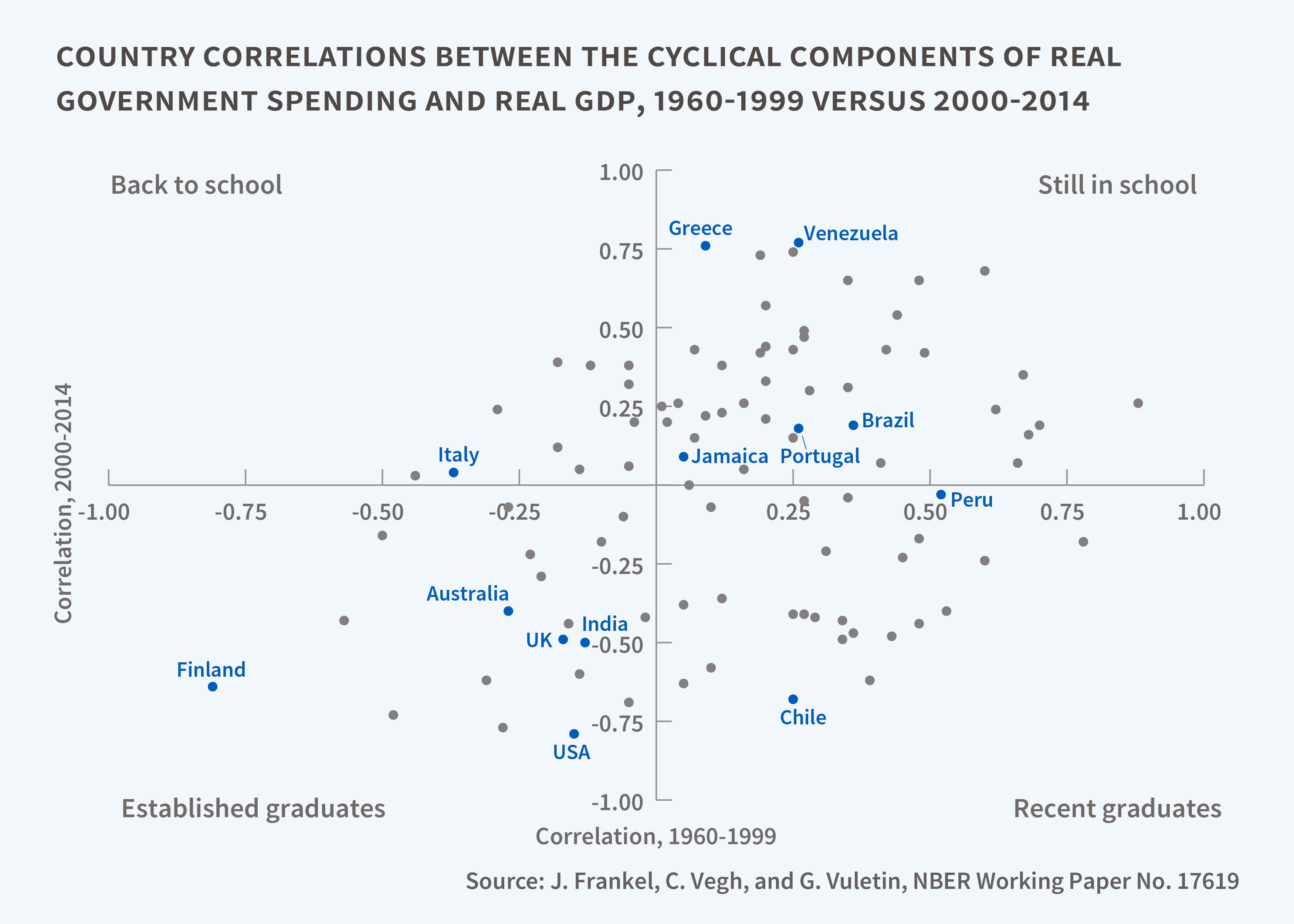

To see how fiscal policy cyclicality has evolved over time, Figure 2 shows, for each of the 96 countries in Figure 1, the correlation between real government spending and real GDP for the periods 1960–1999 and 2000–2014.6 By so doing, the plot is divided into four quadrants:

Established graduates (bottom-left): countries that have always been countercyclical. Not surprisingly, 74 percent of these countries are industrial, including the United States and the United Kingdom.

Still in school (top-right): countries that were originally procyclical and continue to be so. Not surprisingly, 95 percent of these countries are developing. A notable country in this group is Greece, which in fact has become much more procyclical since the year 2000, with the correlation increasing from 0.09 to 0.76.

Back to school (top-left): countries that were countercyclical but then turned procyclical.

Recent graduates (bottom-right): countries that used to be procyclical but have become countercyclical over the last 15 years. Twenty one out of the 24 graduating countries (88 percent) are developing countries. The overall graduation rate for developing countries is 34 percent. As a result, the proportion of developing countries that are procyclical has fallen from 81 percent to 65 percent.

The poster-boy of the graduation movement has clearly been Chile. Between the two periods, Chile's correlation switched from 0.25 to -0.68. In fact, Chile's fiscal stimulus package of close to three percent of GDP in response to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 was among the largest in the developing world.

The key to Chile's graduation was the adoption in the year 2001 of a fiscal rule that requires the government to run a structural balanced budget.7 The structural balance is computed by adjusting the actual balance for the effects on tax revenues of deviations of actual output from trend output and of deviations of copper prices from their long-run value. These trends are based on forecasts produced by an independent group of experts. By construction, a zero structural balance forces the fiscal authority to save in good times and allows it to spend in bad times.

Needless to say, fiscal rules are not a panacea and even Chile broke its own rule in 2009 when, as a result of the stimulus package in response to the global financial crisis, it ran a structural deficit of 1.2 percent. But clearly fiscal rules can be helpful as a guide to sound fiscal policy and, when based on the structural fiscal balance, in drawing the market's attention to the need to adjust for the business cycle when evaluating current fiscal policy.

Even more important perhaps is the overall improvement in the quality of fiscal institutions, including transparent budgetary procedures, fiscal accountability, and broad agreement on fiscal priorities. A structural fiscal rule à la Chile should be viewed as an improvement in fiscal institutions. In fact, the empirical evidence clearly suggests that improvements in the quality of institutions lead to more countercyclical fiscal policy.8

How Effective is Counter- Cyclical Fiscal Policy?

We have established that about a third of developing countries have graduated. This has brought the number of developing countries that have pursued countercyclical fiscal policies over the last 15 years to 35 percent from just 19 percent in the period 1960–1999. The next question, then, is: How effective has countercyclical fiscal policy been?

The size of the fiscal multipliers has, of course, been a perennial question for the United States and, to a lesser extent, other industrial countries. Until quite recently, however, the evidence for emerging countries had, at best, been scant, due to lack of reliable quarterly data. Estimates based on annual data are dubious simply because the main identification mechanism — the Blanchard-Perotti assumption that government spending can react to GDP with only one period lag — strains credibility when applied to annual data.

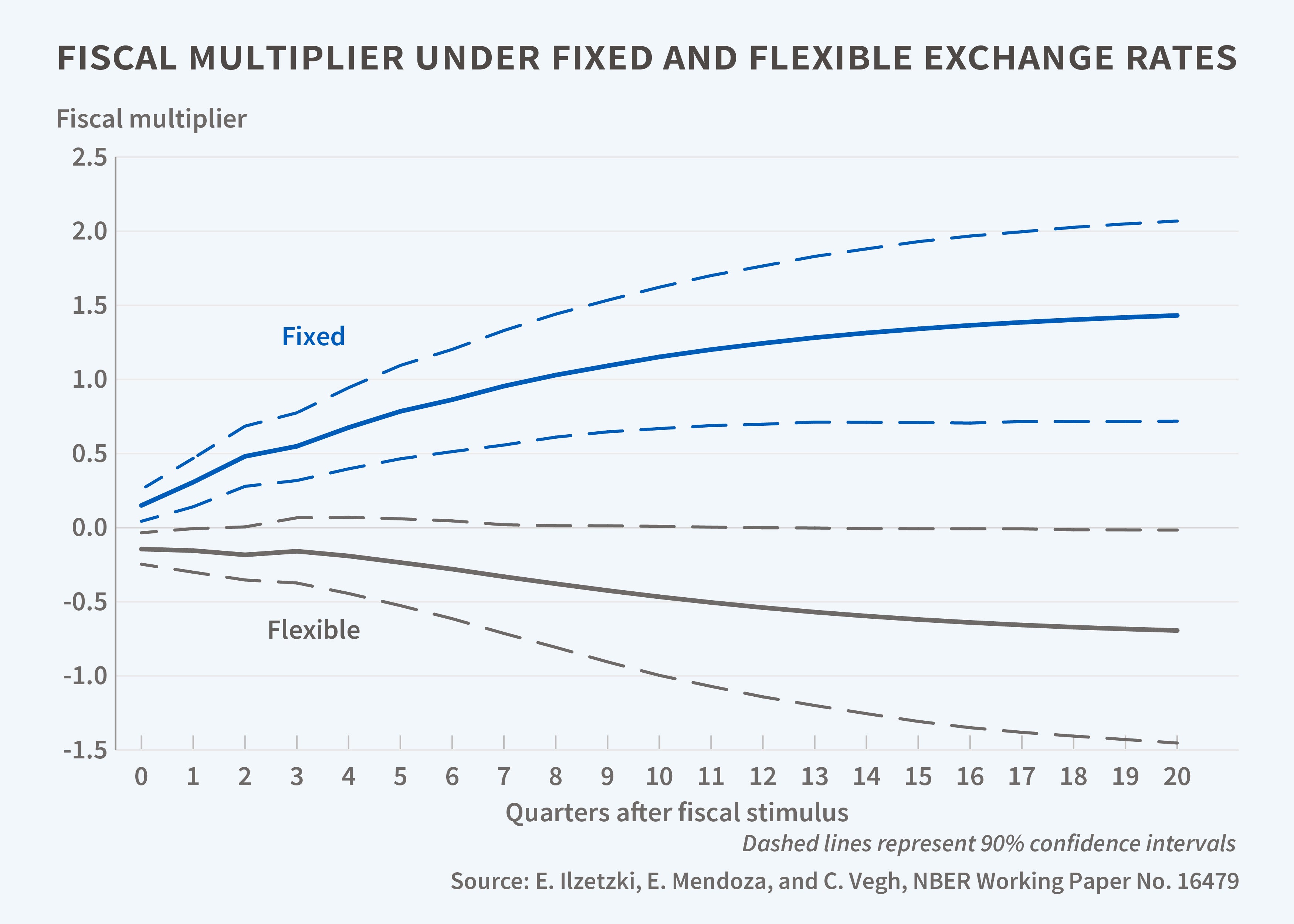

Ethan Ilzetzki, Enrique Mendoza, and I put together a novel quarterly dataset for government spending for 44 countries (20 industrial and 24 developing) from the first quarter of 1960 to the fourth quarter of 2007. Often "quarterly data" is simply interpolated from annual data, so we went to great lengths to ensure that only data originally collected on a quarterly basis was included.9 Perhaps our most important finding is that the size of fiscal multipliers seems to depend critically on country char-acteristics such as exchange rate regime and level of debt. In particular — as illustrated in Figure 3 — we find that the fiscal multiplier is relatively large in economies operating under fixed (or, more generally, predetermined) exchange rates, but is indis-tinguishable from zero under flexible exchange rates. We also show that, on impact, the fiscal multiplier is zero in economies with debt exceeding 60 percent of GDP, presumably reflecting the belief in global capital markets that any fiscal expansion is simply unsustainable.

As Alan Auerbach and Yuriy Gorodnichenko have shown for OECD countries, another critical determinant of the size of the fiscal multiplier is the stage of the business cycle, with the fiscal multiplier being larger in recessions than in booms.10 Moreover, in a study on OECD countries, Daniel Riera-Crichton, Vuletin, and I have shown that whether government spend-ing is increasing or decreasing matters as well. We find that the linear (or single) multiplier after four six-month semesters is 0.40, rises to 1.25 if computed for recessions (in line with Auerbach and Gorodnichenko), and to 2.3 when computed for reces-sions and government spending going up. Intuitively, the bias arises because government spending has a larger effect on output when it increases than when it decreases and, even in OECD countries, there are many instances in which government spend-ing falls in recessions, which biases downward the "true" multiplier.11

Since emerging markets in particular face repeated crises, it is also important to look at fiscal policy responses during crises — as opposed to cyclical characteristics over the regular business cycle — and see how they have evolved. Vuletin and I have looked at fiscal policy in the midst of crises for seven Latin American countries accounting for more than 90 percent of the region's GDP over the last 40 years and concluded that countries such as Chile and Mexico have been able to switch from procyclical to countercyclical fiscal policy responses.12 But the picture is uneven, as countries like Argentina, Uruguay, and Venezuela continue to show a pronounced tendency to contract government spending sharply in recessions.

Eurozone: The New Latin America?

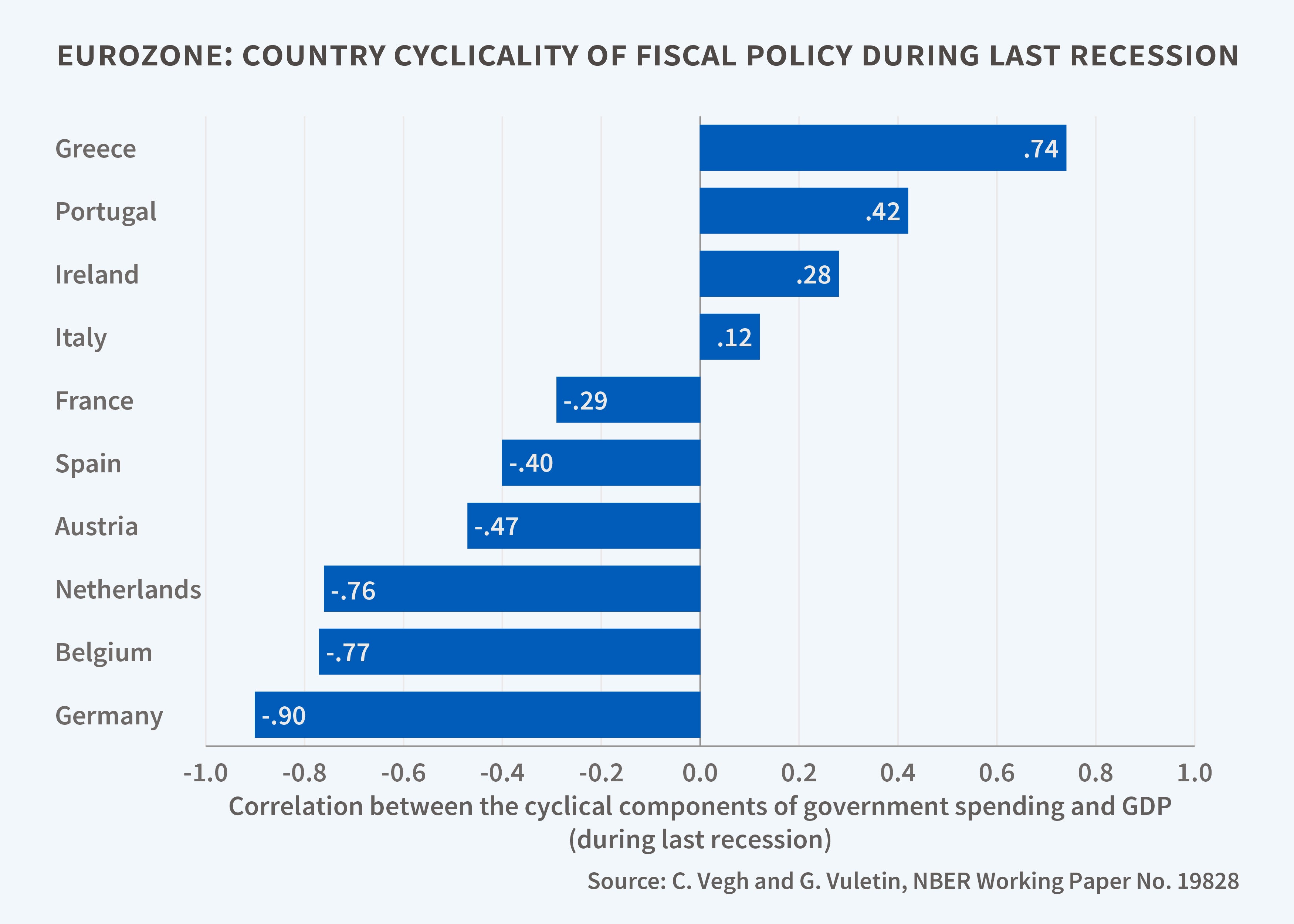

Vuletin and I further show that the fiscal policy response in recent recessions in the eurozone (still ongoing, of course, for countries such as Greece) has been eerily reminiscent of the pervasive response in Latin America several decades ago. Figure 4 shows the correlation between the cyclical components of government spending and GDP from the beginning of the recession to the first quarter of 2013 for 10 eurozone countries. We see that four countries (Greece, Ireland, Italy, and Portugal) have been procyclical, with Greece, not surprisingly, the most procyclical of all.13 We further show that contractionary fiscal policy during bad times extended the duration of the recession, intensified the fall in GDP, and worsened social indicators.

Final Remarks

We should note, in closing, that monetary policy has not escaped the procyclical trap. In fact, over the period 1960–2009, about 40 percent of developing countries pursued procyclical monetary policy.14 When the sample is divided before and after the year 2000, about 35 percent of developing countries are found to have graduated to countercyclical monetary policy.

The source of procyclicality in monetary policy is the need, in the minds of many policymakers in emerging markets, to defend the domestic currency in bad times by raising interest rates. Policymakers often fear, with some justification, that sudden currency depreciation will increase inflation, exacerbate capital flight, and render dollar-denominated debt of both public and private agents more onerous. But whatever the merits, defending the currency in bad times imparts an unavoidable procyclicality to monetary policy.

In sum, while progress has been made in the conduct of macroeconomic policies in emerging markets, many continue to pursue procyclical monetary and fiscal policies. By aggravating already volatile boom-bust cycles, such policies have negative effects on output and social indicators. From a macroeconomic point of view, this is arguably the main challenge faced by developing countries as another cycle of capital outflows and low commodity prices works its way through. Further research in this area may help in identifying factors that may enable more developing countries to adopt countercyclical macroeconomic policies.

Endnotes

I use the terms "emerging markets" and "developing countries" interchangeably, since the prototypical developing country that I have in mind has fairly standard fiscal institutions and is reasonably integrated into world capital markets.

Updated from C. Reinhart, G. Kaminsky, and C. Vegh, "When It Rains, It Pours: Procyclical Capital Flows and Macroeconomic Policies," NBER Working Paper 10780, September 2004, and in M. Gertler and K. Rogoff, eds., NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2004, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 11–53.

C. Vegh and G. Vuletin, "How Is Tax Policy Conducted over the Business Cycle?" NBER Working Paper 17753, January 2012, and American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 7(3), pp. 327–70.

On the former explanation, see A. Riascos and C. Vegh, "Procyclical Government Spending in Developing Countries: The Role of Capital Market Imperfections" mimeo, University of California, Los Angeles, 2003; G. Cuadra, J. Sanchez, and H. Sapriza, "Fiscal Policy and Default Risk in Emerging Markets," Review of Economic Dynamics, 13(2), 2010, pp. 452–69, and S. Bauducco and F. Caprioli, "Optimal Fiscal Policy in a Small Open Economy with Limited Commitment," Journal of International Economics, 93(2), 2014, pp. 302–15. On the latter explanation, see A. Tornell and P. Lane, "The Voracity Effect," American Economic Review, 89(1), 1999, pp. 22–46, E. Talvi and C. Vegh, "Tax Base Variability and Procyclicality of Fiscal Policy," NBER Working Paper 7499, January 2000, and Journal of Development Economics, 78(1), 2005, pp. 156–90, and A. Alesina and G. Tabellini, "Why is Fiscal Policy Often Procyclical?" NBER Working Paper 11600, September 2005, and Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(5), 2008, pp. 1006–36. ↩

J. Frankel, C. Vegh, and G. Vuletin, "On Graduation from Fiscal Procyclicality," NBER Working Paper 17619, November 2011, and Journal of Development Economics, 100(1), 2013, pp. 32–47.

While 2000 is certainly an arbitrary point to break the sample, minor variations do not make a difference.

For a detailed discussion of the Chilean case, see J. Frankel, "A Solution to Fiscal Procyclicality: The Structural Budget Institutions Pioneered by Chile," NBER Working Paper 16945, April 2011, and Journal Economia Chilena, Central Bank of Chile, 14(2), 2011, pp. 39–78.

J. Frankel, C. Vegh, and G. Vuletin, "On Graduation from Fiscal Procyclicality," NBER Working Paper 17619, November 2011, and Journal of Development Economics, 100(1), 2013, pp. 32–47.

E. Ilzetzki, E. Mendoza, and C. Vegh, "How Big (Small?) Are Fiscal Multipliers?" NBER Working Paper 16479, October 2010, and Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(2), 2013, pp. 239–54.

A. Auerbach and Y. Gorodnichenko, "Fiscal Multipliers in Recession and Expansion," NBER Working Paper 17447, September 2011, and in A. Alesina and F. Giavazzi, eds., Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. 63–98.

D. Riera-Crichton, C. Vegh, and G. Vuletin, "Procyclical and Countercyclical Fiscal Multipliers: Evidence from OECD Countries," NBER Working Paper 20533, September 2014, and Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 52(C), 2015, pp. 15–31.

C. Vegh and G. Vuletin, "The Road to Redemption: Policy Response to Crises in Latin America," NBER Working Paper 20675, November 2014, and IMF Economic Review, Vol. 62(4), 2014, pp. 526–68.

Recall from Figure 1 that, historically, Greece and Portugal have been the only two industrial countries with procyclical government spending. Further, Figure 2 shows these two countries as "still in school."

C. Vegh and G. Vuletin, "Overcoming the Fear of Free Falling: Monetary Policy Graduation in Emerging Markets," NBER Working Paper 18175, June 2012, and in D. Evanoff, C. Holthausen, G. C. Kaufman, and M. Kremer, eds., The Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability: How Has It Changed? World Scientific Studies in International Economics, Book 30, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2013).