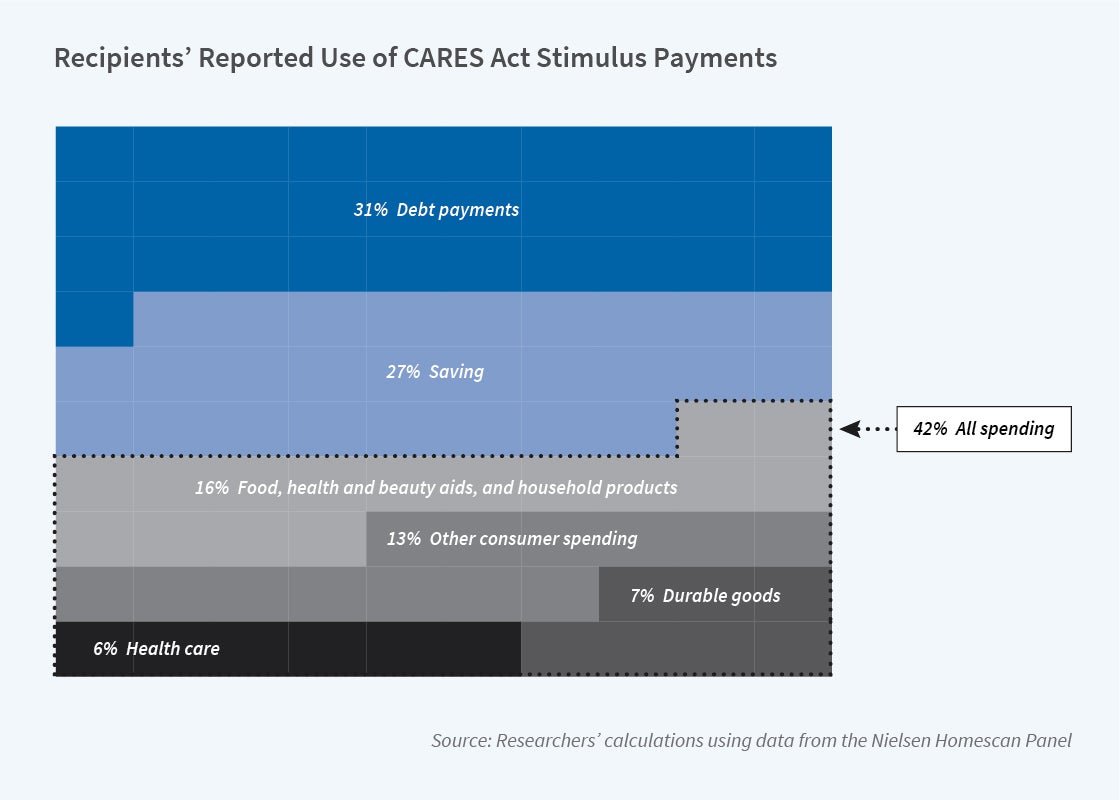

Most Stimulus Payments Were Saved or Applied to Debt

US households report spending approximately 40 percent of their

stimulus checks, on average, with about 30 percent saved and another

30 percent used to pay down debt.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, enacted on March 27, 2020, was designed to bolster household incomes and support consumer spending. It achieved the first goal, but had only a modest impact on consumer spending. Survey data on household behavior suggest that nearly 60 percent of the stimulus spending went to pay off debt or was saved. Of the roughly 40 percent that was spent on goods and services, consumers favored food and beauty products rather than large durables like cars or appliances. The averages mask considerable variation among households. Some 20 percent saved virtually all of their stimulus check; another 40 percent spent nearly all of it. Roughly 20 percent used most of their federal payment to reduce their debts.

These findings in How Did US Consumers Use Their Stimulus Payments? (NBER Working Paper 27693) reflect general patterns seen in 2001 and 2008, when the federal government also countered economic downturns with direct transfer payments. The 2020 payments, however, were much larger and the recipients were somewhat less likely to spend than in the past.

Why didn’t Americans spend more? Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber put forward two possible explanations. One is that the pandemic-induced lockdown closed down so many businesses and recreational and travel options that recipients could not spend the whole transfer. The other is that the law of diminishing returns kicked in. They find that the larger the stimulus check, the less likely recipients are to spend it.

The researchers say this suggests that there is a bound on how much stimulus can be generated through direct transfers to households, and that in the face of large crises, decision-makers may want to consider a broad range of policies targeting aggregate demand, with direct transfers being only a part of the fiscal policy response.

Less than four months after the CARES Act provided one-time payments of $1,200 to each qualifying adult and another $500 for each qualifying child, with payments phased out at higher incomes, the Nielsen Homescan surveyed some 46,000 people. The researchers added questions about the use of stimulus funds to the quarterly survey’s usual battery of questions, which ask about spending, investment, labor status, and expectations about the economy. The survey was completed by about 12,000 recipients, a larger response pool than either the Survey of Consumer Expectations — about 1,500 respondents per wave — or the Michigan Surveys of Consumers Attitudes, with roughly 500 respondents per wave.

The researchers discovered a number of interesting patterns. Larger households leaned toward spending most of the money. Seniors tended to pay down debt while younger and more educated households were more likely to save the payments. Those who were out of the labor force or who lived with parents were more likely to spend. African Americans were more likely to use most of their stimulus money to pay down debts, and Hispanics were more likely to spend.

One of the most striking findings involved individuals in liquidity-constrained households, defined as those who reported that they could not cover an unexpected bill equal to their monthly income. While many economic models assume that this group has a high marginal propensity to spend out of unexpected income, the researchers found they were no more likely to spend than individuals who were not constrained. Instead, they were very likely to pay down debt.

The data suggest the stimulus payments had little impact on job-seeking: among unemployed individuals who received the payment, two-thirds said it had no effect on their job-search decisions, and more than 20 percent reported that the stimulus actually caused them to look harder for a job.

— Laurent Belsie