What Charging Habits of Owners Reveal about Electric Vehicle Use

At-home charging data from California suggest that electric vehicles have been driven many fewer miles per year than their gasoline-powered counterparts.

Estimates of the environmental benefits of electrification of the passenger vehicle fleet depend on the number of miles that each new electric car will displace from the gasoline-powered fleet. Using new data on the electricity use of electric vehicle (EV) owners in northern California from 2014 to 2017, Fiona Burlig, James B. Bushnell, David S. Rapson, and Catherine Wolfram report in Low Energy: Estimating Electric Vehicle Electricity Use (NBER Working Paper 28451) that the average EV charges less than half of the amount that has been assumed in projections by state regulators. When combined with public data on nonresidential charging, these results imply that the average battery electric vehicle (BEV) drove about 6,700 miles per year and that plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) traveled only 1,700 miles per year with electricity.

The research matches California Department of Motor Vehicles registration records with Pacific Gas and Electric electricity consumption data for 2014 through 2017. The sample comprises 57,290 of the 423,297 EVs in California, which (both then and now) is home to around half of all EVs in the US.

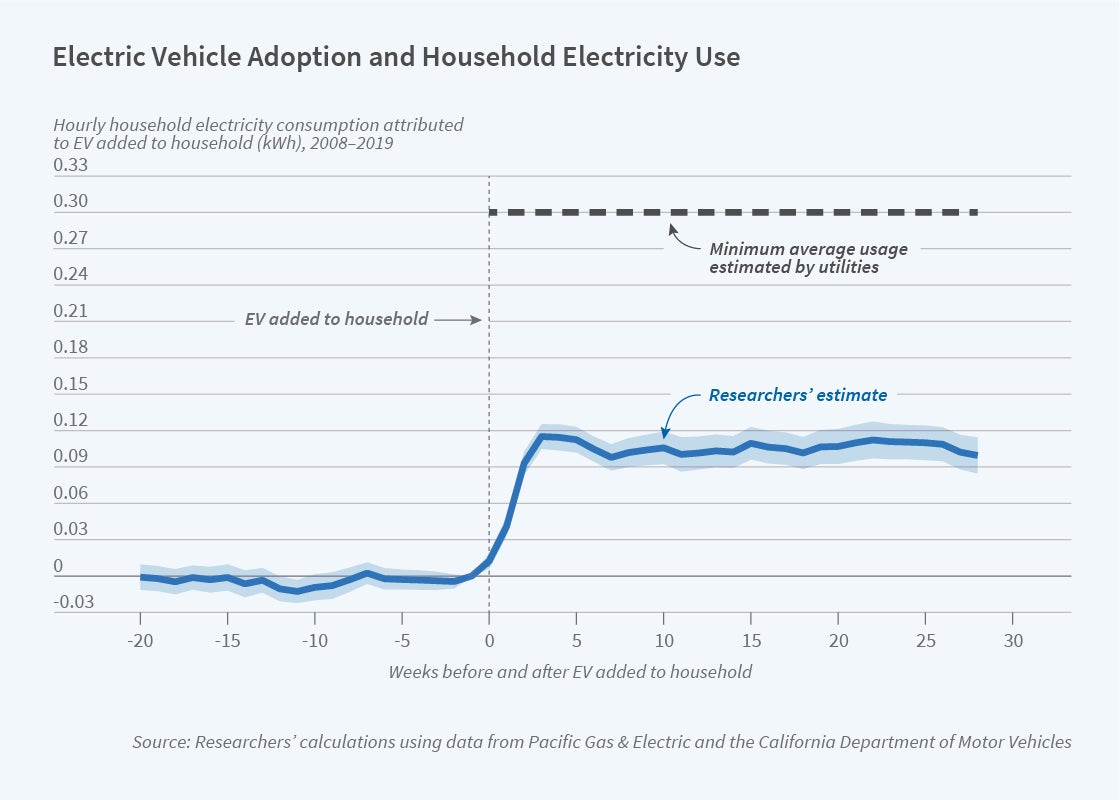

The researchers estimate that regular charging of an electric vehicle increased a household’s average electricity consumption by 2.9 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per day, or 0.121 kWh per hour. They find that electricity consumption rose within a couple of weeks of an owner registering an EV, and that it largely remained constant for the next six months. Increased electricity consumption was concentrated between the hours of 10 pm and 6 am, suggesting drivers charge their EVs when they come home and leave them plugged in overnight. This hourly pattern has implications for the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions associated with vehicle electrification. In California, CO2 emissions associated with electricity consumption are highest overnight, when the marginal electricity generator is likely to be gas-fired rather than solar or wind powered.

The researchers’ estimate of average daily per-vehicle EV charging consumption, 2.9 kWh, is far below the estimate of California’s utilities of 7.2 to 8 kWh. The utility estimate was based on the small and likely unrepresentative sample of households with dedicated EV meters; by contrast, this new study uses data on tens of thousands of cars, which are broadly representative of California’s EV fleet.

What explains low EV electricity consumption? One possibility is that EVs are being charged primarily away from home. This would run contrary to existing administrative data. By the researchers’ estimates, in order for EVs to be driven as much as their gasoline-powered counterparts, away-from-home charging kWh would have to be three times what is currently reported to state regulators. The researchers reason that this is unlikely because Low Carbon Fuel Standard credits, worth between $0.20 and $0.25 per kWh — well above the price of electricity — are paid to chargers who report.

Assuming the administrative data are correct, the researchers suggest several possible explanations for low EV electricity consumption. First, relatively early EV adopters may have different baseline driving behavior than the average car owner. The researchers observe that EV owners tended to use more electricity in their homes prior to EV purchases than households who did not buy an EV during the sample period, implying unobservable differences.

Second, drivers may perceive EVs as less convenient than gasoline-powered vehicles due to range anxiety or other attributes. Relatedly, EVs often make up just one piece of a household’s vehicle portfolio. The researchers find a relatively weak relationship between kWh consumed and vehicle battery size, with the exception of Teslas, which both have a larger battery than other sample vehicles and use substantially more electricity. Finally, it is possible that low EV usage is attributable to high electricity prices, and that households might use their EVs more if electricity cost less.

“If EVs are being driven as much as conventional cars, it speaks to their potential as a near-perfect substitute for vehicles burning fossil fuels,” the researchers write. “If, on the other hand, EVs are being driven substantially less than conventional cars, it raises important questions about the potential for the technology to replace a vast majority of trips currently using gasoline.”

— Brett M. Rhyne