Employment Effects of Demolishing Distressed Public Housing

Children from large housing projects demolished in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HOPE VI program were earning 14% more at age 26 than those in the control group.

Between 1996 and 2003, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded nearly $400 million in grants to localities for the demolition of more than 57,000 public housing units. Through this HOPE VI program, HUD sought to improve families’ living conditions by demolishing severely distressed subsidized public housing and relocating those who lived in it.

In The Children of HOPE VI Demolitions: National Evidence on Labor Market Outcomes (NBER Working Paper 28157), John C. Haltiwanger, Mark J. Kutzbach, Giordano E. Palloni, Henry O. Pollakowski, Matthew Staiger, and Daniel H. Weinberg consider the HOPE VI program’s effects on young adults who were exposed to the program as children.

Using records from HUD and the Census Bureau, the researchers generated a dataset of 18,500 children from 160 demolished housing projects and examined their labor market status at age 26. From the same records, the researchers generated a control group of children from 570 public housing projects that were not demolished.

Children exposed to a HOPE VI demolition earned substantially more — about 14 percent, or $622 — at age 26 than non-exposed children. The probability of working all four quarters of the year was 1.6 percent greater for those affected.

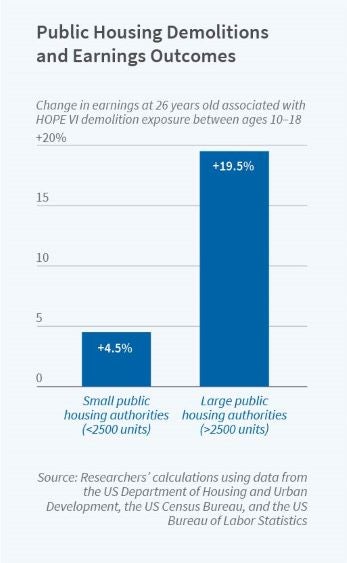

On average, children from large housing projects — those of more than 2,500 units — experienced more benefits. Earnings at age 26 for those from large projects were 19.5 percent greater than for those in the control group, compared with just 4.5 percent for those in smaller projects. The age at which a child moved was not a factor. Also, moving had no effect on job market outcomes for the parents; earnings for heads of household remained unchanged after relocation.

Children who lived in neighborhoods that were denser, poorer, and farther from jobs prior to the demolition benefited most from the program. But the gains are difficult to attribute to improvements in either the children’s home or neighborhood environment. The families did not move to higher quality neighborhoods, as measured by school quality or the poverty rate. The new neighborhoods were significantly better, though, in terms of the ratio of jobs to people, average commute time, and a “job proximity index” constructed by HUD.

The demolitions transformed the neighborhoods in which the HOPE VI projects were originally located. Public housing projects, particularly large projects, often provide housing to large numbers of people in geographically concentrated areas. This results in many job-seekers competing for nearby work. Demolitions reduced population density and raised the job-to-people ratio by 22 percent. Even HOPE VI children who remained near their original housing project experienced an improvement in job proximity. Once again, the findings are driven by large projects. The researchers found no evidence that HOPE VI demolitions improved geographic proximity to jobs for former residents of small housing projects, and some evidence that they reduced it.

– Brett M. Rhyne