The Economics of Counterfeiting

Intellectual property (IP) rights and counterfeiting have permeated everyday lives as globalization, technological advancement, and AI flourish. Interbrand estimates that the brand value of Louis Vuitton was $26.3 billion in 2023, as an example of the IP value of brands. The values brands possess generate incentives for counterfeiting and imitation. Counterfeiting cuts across countries and industries. Notably, counterfeit footwear has topped the seizure list of the US customs service for four years, accounting for nearly 40 percent of total seizures.1 The origins, impacts, and remedies of counterfeits and the protection of IP are pertinent topics to address.

My research agenda is centered on the economics of innovation, IP, and brand management against counterfeiting. At a broad level, my interests in branding and IP motivate the analysis of the strategic roles of IP development and protection, the impact of counterfeiting and imitation, and brand management in emerging markets.2 The goal of my research is to understand a) the origins, impacts, and remedies of counterfeiting and imitation, b) how IP laws and policies shape incentives for innovation and the marketing of innovation, and c) the relationship between intangible IP and economic performance. I explore these questions to better understand how marketers can more effectively respond to IP policies and devise IP strategies. In addition, my research offers insights into ways to increase consumer surplus and improve social welfare.

My primary research involves understanding the impact counterfeiters can exert on the market. For companies, brands are valuable IP and strategic assets, a source of competitive advantage. For consumers, brands ideally serve as a guarantee of authenticity and quality. For policymakers, branding investments affect social welfare and, in the long run, the rate of economic growth. My research sheds light on the ways in which brand infringement and protection interact with the broader economy and subsequently generate important implications for government and managers alike. It does so in three ways: a) by investigating the role of trademarks—the form of IP that protects brand exclusivity—and presenting evidence that informs trademark policy choices and branded firms’ self-enforcement strategies; b) by exploring how brand management activities against counterfeits affect market competition and innovation, thus relating branding to broader company strategies and industrial organization; and c) by drawing analogies between the concepts of brand and collective reputation to understand how false victim signals free ride on the authentic victim “brand,” tarnish its reputation, and harm social welfare.

I identify heterogeneous sales impacts of counterfeiting on different quality tiers and brands. I evaluate how firms can better manage their IP and branding strategies in a market with counterfeits or imitations, including adjustment of the extent, nature, and direction of innovation, pricing, investment in self-enforcement, and vertical integration of downstream retail channels. The set of strategies are complements rather than substitutes. I further explore how income inequality and status signaling can drive the demand for counterfeits and how personality affects individual attitudes toward counterfeits and counterfeiters as well as incentives to counterfeit.

The General Marketing Impact of Counterfeiting

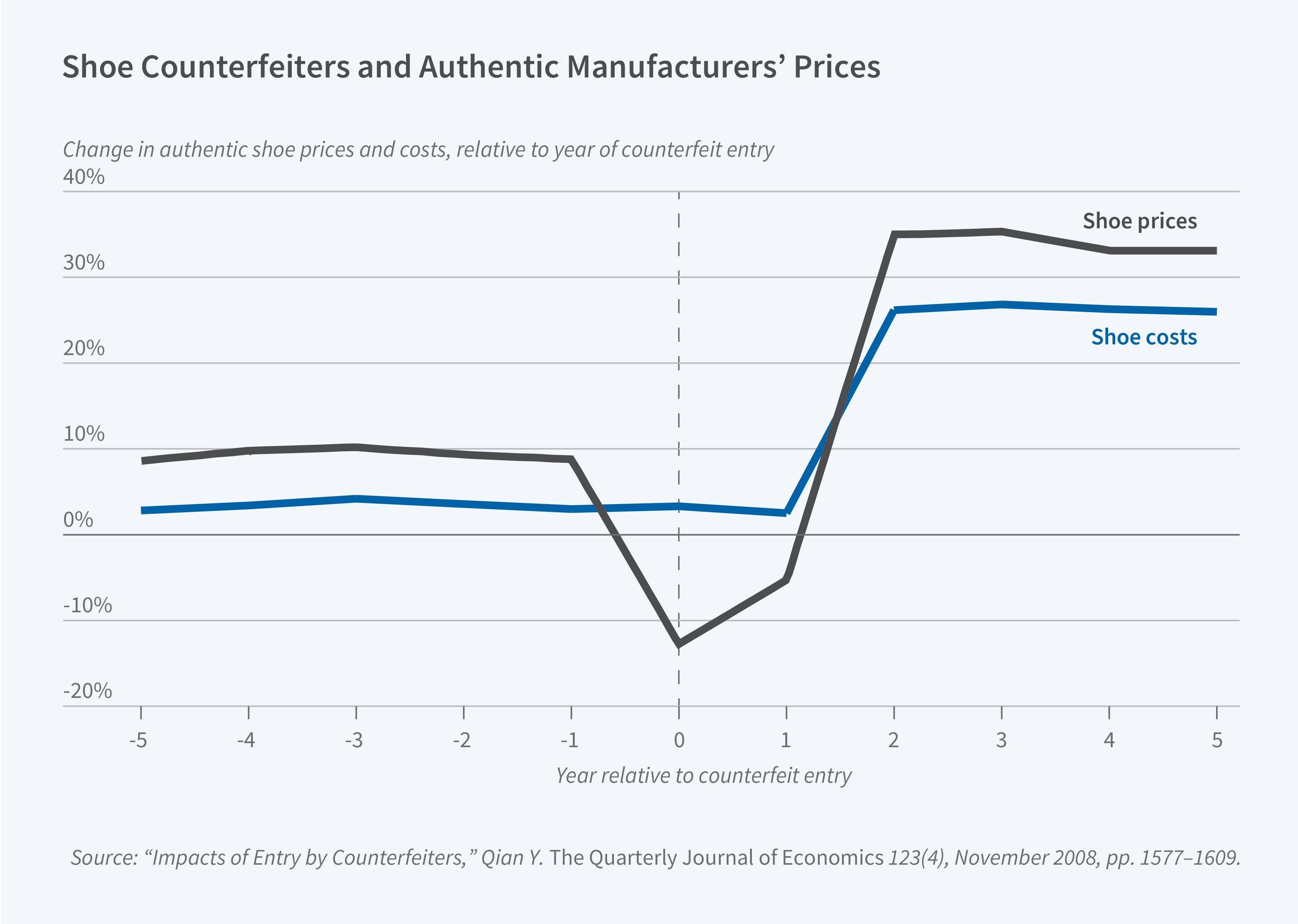

One strand of my research involves an econometric attempt to study the general marketing impact of entry by counterfeiters under weak IP protection.3 I collected new panel data from Chinese shoe companies from 1993 to 2004. By exploiting the discontinuity of government enforcement efforts in the footwear sector in 1995 and the differences in authentic companies’ relationships with the government, I identify and measure the effects of counterfeit entry on authentic prices, quality, and other market outcomes. My analysis shows that counterfeit entry stimulates the original producer to offer a higher-quality product at a higher price. In addition, company-level self-enforcement activities and downstream vertical integration of licensed company stores are effective in deterring counterfeit entry or reducing counterfeit sales. For companies conducting business in developing countries, relationships with local governments play important roles in brand management.

The aforementioned strategies that branded firms adopt to combat counterfeits can be considered manifestations of endogenous sunk costs (ESC) that can sustain market dominance.4 My work provides a theoretical framework for understanding counterfeiting.5 I build upon a vertical differentiation model with endogenous quality and other ESC. I model two layers of asymmetric information that counterfeiting frequently generates: First, there is asymmetric information between a counterfeiter and buyers. Second, some buyers may show off the counterfeits to signal their fake status. I find evidence that legitimate firms react by establishing essentially a separating equilibrium that signals their goods’ origin by investing in quality, developing retail stores, fostering self-enforcement, and raising prices. In contrast, the conventional wisdom in developing countries is that weak enforcement forces legitimate firms to accept lower prices and quality in what amounts to a pooling equilibrium. I find the former outcome in a common consumer good: footwear. Brands did not innovate prior to entry by counterfeiters, even though there was substantial competition among the horizontally differentiated brands. My model conceptualizes and resolves this puzzle: Due to the knockoff nature of counterfeits, they enter the vertical quality line of the infringed brand. Such competition exerts unique pressure on the brand to move up the quality ladder in a market where the brand otherwise enjoys monopolistic power in its own niche. This suggests that a substantial portion of the rents from innovation accrue not from technological novelty but from embedding innovation in brands and distribution systems insulated from fringe competition.

My findings suggest that public-private partnerships in enforcement could be effective, leveraging both the private firm’s insider knowledge and the government’s sanction power. Inviting collaboration with the brands that have vested interests and incentives to combat illegal activities such as counterfeiting could lead to more efficiency.

The Nature and Direction of Innovation Responses to Counterfeiting

The theoretical model described above provides the microfoundations of consumer deception by a counterfeiter and an authentic firm’s tactics (distribution choices and self-enforcement) to mitigate it. My research with Qiang Gong and Yuxin Chen provides a deeper theoretical examination of the nature and extent of innovation by disentangling the attributes of quality. We focus on the differential impact on two dimensions of quality.6 The fact that counterfeiters usually mimic an authentic product’s design but offer inferior functional quality has important implications for authentic producers’ incentives to innovate and the nature of innovation. This theoretical framework helps unravel these complexities with intuitive closed-form solutions. While prior literature primarily defines a prestige effect as a function of the total sales of the brand (and its counterfeits) and one-dimensional quality, we decompose quality to a finer level. In addition, we endogenize quality choices and analyze the model under producers’ flexible cost structures. The findings provide practical guidance on brand-protection strategies under different market conditions where counterfeits may vary by production cost and pervasiveness.

This research contributes to the literature on counterfeits and product quality differentiation. Our model extends Philip Nelson’s constructs on searchable and experiential goods to quality dimensions within a good.7 For many products, including authentic brands subjected to counterfeit imitation, some quality traits are observable (e.g., stitching, appearance) and others unobservable (e.g., durability) at the time of purchase. Counterfeits, by definition, share some searchable (observable) quality traits with the authentic brand, whereas the deception revolves around the experiential (unobserved). Our model incorporates two dimensions of endogenous vertical quality as well as endogenous price under asymmetric information and yields closed-form solutions as testable predictions of counterfeit competition. In related work, we generalize the model framework to capture continuous quality dimensions.8 Untangling these two quality dimensions yields insights into the unique impact counterfeits can have on branded products compared with a generic entry.

The topic is relevant to emerging markets and the results shed light on an interesting feature of these markets. Emerging markets are characterized by relatively low enforcement of anti-counterfeit regulation. Chinese counterfeit shoe manufacturing, which is weakly regulated, is the setting for the theory’s empirical test. Therefore, this research can provide insights into marketing in emerging markets. A key result is that at low levels of counterfeiting, the brand tolerates some counterfeiting by allowing the counterfeiter to pool on the searchable dimension. However, if counterfeiting grows too much, the brand separates by making the quality on the observable dimension sufficiently high that the counterfeiter cannot reproduce the same high level of quality on this dimension. We formalize this notion as the “self-correcting property” of emerging markets—if it anticipates too much counterfeiting, the brand preempts it. We also provide supportive anecdotal and empirical evidence. Based on detailed shoe characteristics data, we find that branded companies improved their searchable quality dimensions after infringement by counterfeiters, but not their experiential dimensions.

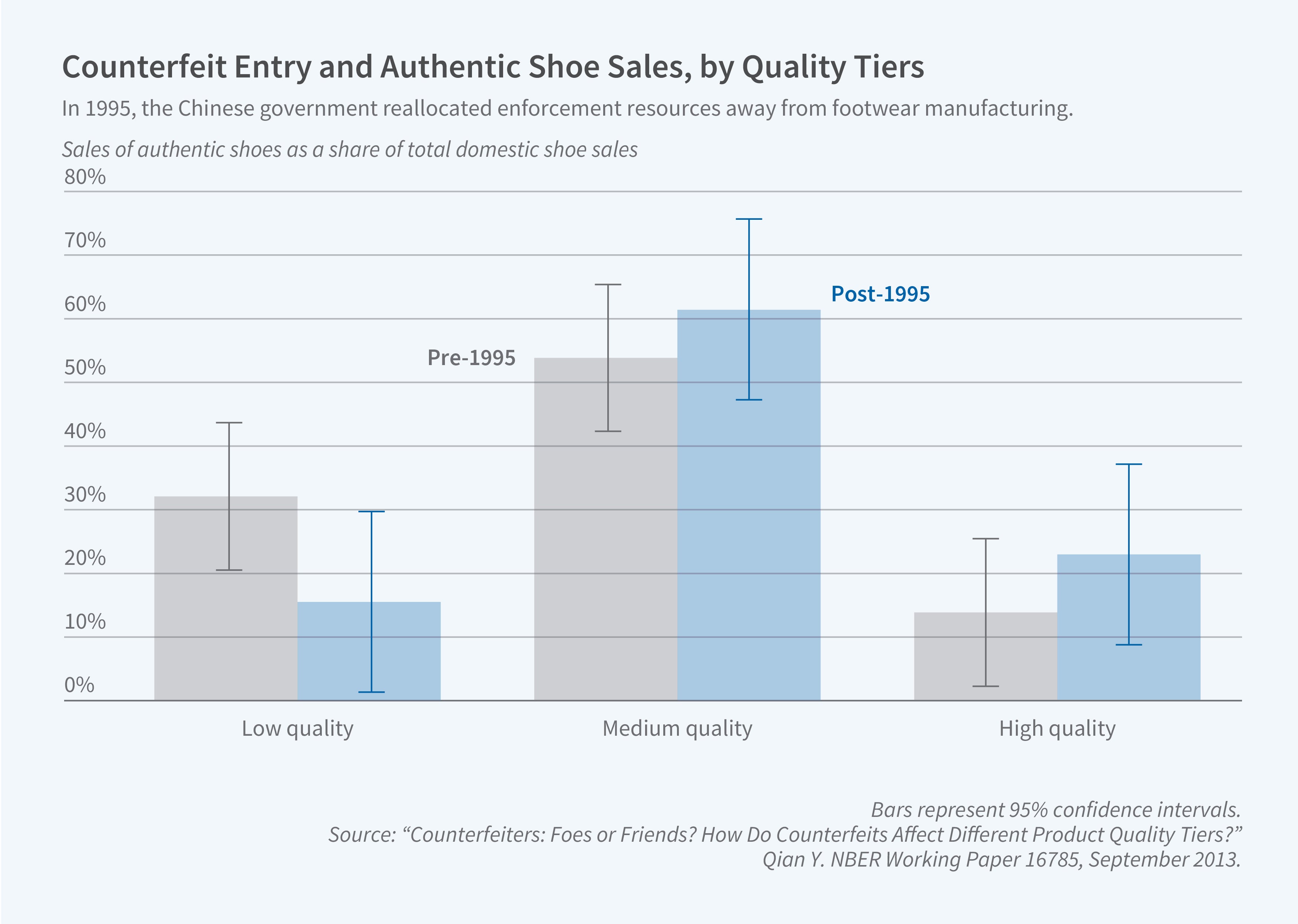

While branded firms were shown to innovate in the face of counterfeiting, are such incentives sustainable? In order to effectively guide priorities for and directions of innovation and enforcement strategies, it is crucial to understand the sales impacts of counterfeits on authentic products of different types and quality tiers and on brands of different natures and life stages. However, the extant literature has left this topic largely unexplored, due in part to insufficient data. My research fills this void by investigating the specific sales impacts of counterfeits through field and experimental methods, including examining how product quality, product type, brand age, and brand reputation mediate these effects.9 Such sales-related findings go well beyond the general marketing impacts of counterfeiting and shed much-needed light on potential incentives and directions for innovation and enforcement as well as academic, managerial, and policy-related implications.

Analyses using economic theory, empirical modeling, and randomized lab experiments arrive at convergent results. I identify some of the benefits (advertising) and costs (substitution) to legitimate brands from counterfeit imitation. The advertising effect outweighs the substitution effect for high-end products and the business-stealing effects dominate for low-end products where counterfeits are closer substitutes. I further identify moderators of the advertising effects of counterfeiting and find that the advertising effects are larger for brands that are younger and less famous at the time of infringement and for products that are more fashionable and tailored to younger customers. Such heterogeneous sales impacts could steer innovations along the respective dimensions. The consistency of results from the Chinese field panel data and US-based lab experiments demonstrates that the panel-based findings have implications beyond China, and the generalizable principles are theorized with a vertical differentiation model of multiproduct firms.10 I have identified similar positive spillover effects of an entrant (e.g., outlet store) in other contexts in marketing, such as line extensions.11

Varying Effects of Counterfeiting by Time, Sector, and Region

In addition to estimating the overall average treatment effects of entry by counterfeiters, I estimate the dynamic and heterogeneous impacts and the factors underlying any heterogeneity in brand management responses. I have tracked the long-term sales impact of counterfeiting for three quality tiers of brands. I show that the positive advertising effects on the high-end product sales and negative substitution effects on the low-end product sales lingered for years. Gilles Grolleau, Juliette Evon, and I find that the heterogeneous effects of counterfeiting are corroborated in the wine industry.12 Alex Cuntz and I find an overall negative counterfeiting effect on R&D and net sales as well as unusual positive effects for the broad sector of tools, materials, and vehicles.13 Infringements by piracy of differing quality levels cause heterogeneous effects for different brands, whether they are plaintiffs or defendants in trademark litigation.14 The same is true for movie producers and theaters with regard to box-office revenues before and after launch.15

Understanding the heterogeneous effects of counterfeits on product and brand types helps to paint a more complete picture of counterfeits’ impact as well as provide more specific guidance. In even the wealthiest nations, resources are constrained and prioritizing enforcement efforts based on the heterogeneous impacts of counterfeiting is crucial.16 This stream of research therefore contributes to the broader literature on how firm responses to their legal environment could have important moderating effects on the impact of IP protection.

Demand for Counterfeiting

In order to propose effective IP and brand-management strategies, it will also be helpful to understand what drives the demand for counterfeits and what affects purchasing behavior. Hui Xie and I employ new nonparametric data fusion methods to develop comprehensive databases that overcome data constraints when studying consumer counterfeit purchase behavior.17 We examine the branded company’s internal records and consumer survey datasets simultaneously and find that such data fusion helps us to develop databases that enable studying the relationships between counterfeit purchases and various marketing elements, such as consumer purchase motivations, behaviors and attitudes toward the authentic product, and the brand’s marketing channels, promotions, and advertisements.

The analysis reveals systematic differences in the characteristics of consumers with different counterfeit-purchase outcomes. In particular, consumers who did not purchase counterfeits in the past year have more positive attitudes toward the prices of authentic products and tend to use the products for work and in social interactions. Furthermore, they place more emphasis on the health, safety, and social interaction benefits of branded products. Therefore, one potentially useful strategy would be to use advertisements to stress these authentic-product benefits compared with those of counterfeit products. This also indicates the importance of educating consumers about the potential hazards of purchasing counterfeits, which some authentic firms have already been doing. The analyses additionally reveal the important role of the internet in counterfeit purchases.

Besides the substantive contributions, we show methodologically how combining complementary datasets through data fusion can help extract new information about counterfeit purchase behaviors and suggest potential measures for fighting counterfeits, which would not be feasible if these datasets were analyzed separately. This study also opens the door to developing data fusion methods to balance data disclosure and privacy protection, which will only gain importance in this AI age.18 We also propose new IV-free causal inference methods as summarized in a recent NBER paper, which could enable analyses beyond correlation in the era of syndicated and unstructured data.19

The Counterfeit Personality

While the previous section highlights my work on probing into the origins of counterfeiting on the demand side, my recent research turns from counterfeit products to the counterfeit personality. Building on the victimhood and moral identity literature, Ekin Ok, Brendan Strejcek, Karl Aquino, and I explore the personality traits associated with counterfeiting, both in terms of attitudes toward counterfeits and counterfeiters as well as the propensity for counterfeiting and fraudulent behavior.20 We show that the virtuous victim signal, as a manifestation of Dark Triad personality traits, predicts a person’s willingness to engage in and endorse ethically questionable behaviors, such as purchasing counterfeit products.

Mingyuan Ban, Qiang Gong, Aquino, and I further study the impact of false victim signaling in the charity market, applying and extending the collective reputation theoretical framework. We directly model three types of individuals with different personalities and incentives who signal their victim status.21 Our analyses of social welfare under the honest, dishonest, and mixed equilibria shed light on key parameters that could potentially serve as policy instruments for improving social welfare. We also reveal that the mechanisms analogous to bank runs and lemons markets could arise in the victims’ market as much as in other markets. In particular, when charity resources are scarce, more strategic signalers could rush to emit false victim signals and drive the market to the dishonest equilibrium and lower social welfare. The need for screening signalers could drive up the psychological costs to authentic victims to the extent that they voluntarily drop out of the market and suffer alone, resulting in misplaced charity funds and severe deadweight losses. When there is psychological utility associated with cheating for the hedonic signalers, the social welfare consequences are even worse.

Looking ahead, there are ever increasing opportunities in this information age to generate timely insights in a world with increasingly pervasive counterfeits and imitations, to help people discern authenticity, and to aid policymakers in executing justice gracefully and effectively.

Endnotes

“Inside the Knockoff-Tennis-Shoe Factory,” Schmidle N, New York Times, August 19, 2010.

“Do National Patent Laws Stimulate Domestic Innovation in a Global Patenting Environment? A Cross-Country Analysis of Pharmaceutical Patent Protection, 1978-2002,” Qian, Y. Review of Economics and Statistics 89(3), August 2007, pp. 436–453. “Intellectual Property Rights and Access to Innovation: Evidence from TRIPS,” Kyle M, Qian Y. NBER Working Paper 20799, December 2014. “Blockchain for Timely Transfer of Intellectual Property,” Cai D, Qian Y, Nan N. NBER Working Paper 30913, March 2025. “The Impact of University Patent Ownership on Commercialization,” Wang J, Qian Y. NBER Working Paper 31021, December 2024.

“Impacts of Entry by Counterfeiters,” Qian Y. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(4), November 2008, pp. 1577–1609.

Sunk Costs and Market Structure: Price Competition, Advertising, and the Evolution of Concentration, Sutton J. Cambridge, MA and London, England: The MIT Press, 1991.

“Brand Management and Strategies Against Counterfeits,” Qian Y. NBER Working Paper 17849, July 2013, and Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 23(2), Summer 2014, pp. 317–343.

“Untangling Searchable and Experiential Quality Responses to Counterfeits,” Qian Y, Gong Q, Chen Y. Marketing Science 34(4), July-August 2015, pp. 522–538.

“Information and Consumer Behavior,” Nelson P. Journal of Political Economy 78(2), March-April 1970, pp. 311–329.

“Untangling Searchable and Experiential Quality Responses to Counterfeits,” Qian Y, Gong Q, Chen Y. In Handbook of Innovation and Intellectual Property Rights: Evolving Scholarship and Reflections, Park WG, editor. Cheltenham, England and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024.

“Counterfeiters: Foes or Friends? How Do Counterfeits Affect Different Product Quality Tiers?” Qian Y. NBER Working Paper 16785, September 2013, and Management Science 60(10), October 2015, pp. 2381–2400.

“The Economics of Counterfeiting Consumption,” Qian Y. In The Luxury Economy and Intellectual Property: Critical Reflections, Sun H, Beebe B, Sunder M, editors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015.

“Multichannel Spillovers from a Factory Store,” Qian Y, Anderson E, Simester D. NBER Working Paper 19176, June 2013.

“How Fine Wine Producers Can Make the Best of Counterfeiting,” Grolleau G, Evon J, Qian Y. Strategic Change 31(5), August 2022, pp. 515–522.

“The Impacts of Counterfeiting on Corporate Investment,” Cuntz A, Qian Y. Journal of Economic Development 46(2), June 2021, pp. 1–40.

“Brand Value and Stock Markets: Evidence from Trademark Litigations,” Coughlan AT, Kamate V, Qian Y. S&P Global Market Intelligence, December 2014, and in Handbook of Innovation and Intellectual Property Rights: Evolving Scholarship and Reflections, Park WG, editor. Cheltenham, England, and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024.

“Assessing the Quality of Illegal Copies and Its Impact on Revenues and Distribution,” Koschmann A, Qian Y. NBER Working Paper 27649, August 2020.

“The Economic Effects of Counterfeiting and Piracy: A Review and Implications for Developing Countries,” Fink C, Maskus KE, Qian Y. The World Bank Research Observer 31(1), February 2016, pp. 1–28.

“Which Brand Purchasers Are Lost to Counterfeiters? An Application of New Data Fusion Approaches,” Qian Y, Xie H. Marketing Science 33(3), May-June 2014, pp. 437–448.

“Drive More Effective Data-Based Innovations: Enhancing the Utility of Secure Databases,” Qian Y, Xie H. NBER Working Paper 19586, October 2013, and Management Science 61(3), February 2015, pp. 520–541.

“A Practical Guide to Endogeneity Correction Using Copulas,” Qian Y, Koschmann A, Xie H. NBER Working Paper 32231, April 2025.

“Signaling Virtuous Victimhood as Indicators of Dark Triad Personalities,” Ok E, Qian Y, Strejcek B, Aquino K. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 120(6), July 2021, pp. 1634–1661.

“The Impact of Counterfeit Victims in the Victim Marketplace,” Ban M, Qian Y, Gong Q, Aquino K. NBER Working Paper 33327, January 2025.