The Changing Structure of American Innovation

The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine was a result of the joint efforts of three types of organization. University of Pennsylvania researchers, notably Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, performed some of the foundational research. Startups, including BioNTech, Moderna, and Arbutus, among others, developed key elements of the technology required to safely deliver the vaccine. Established pharmaceutical firms, notably Pfizer, were responsible for testing, production, and distribution. Pfizer and its partner BioNTech developed the vaccine internally, whereas Moderna, the other major supplier of COVID vaccines in the United States, benefited from significant government research funding. This division of labor in innovation, which allowed multiple firms to contribute, is a notable component of the US innovation ecosystem.

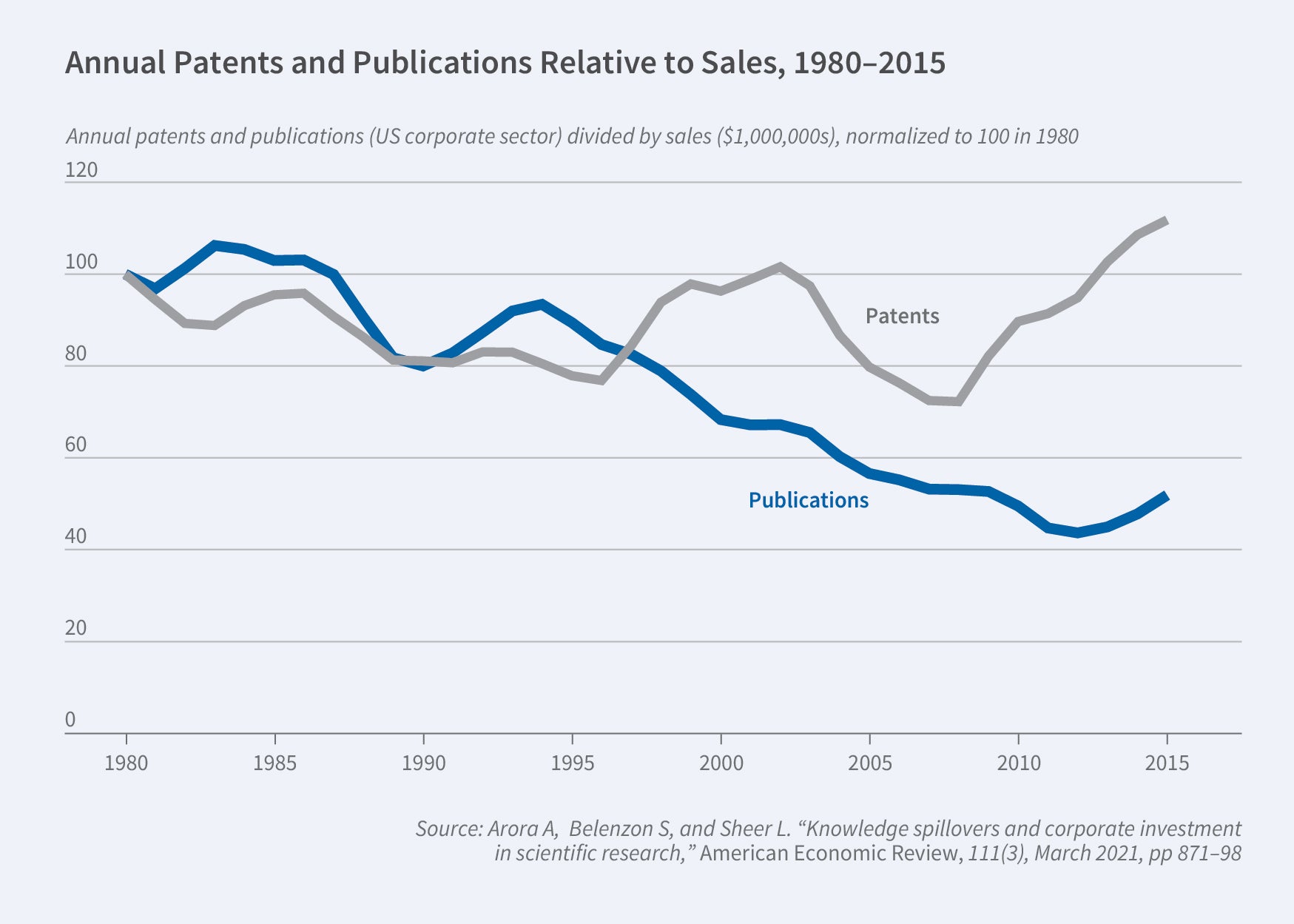

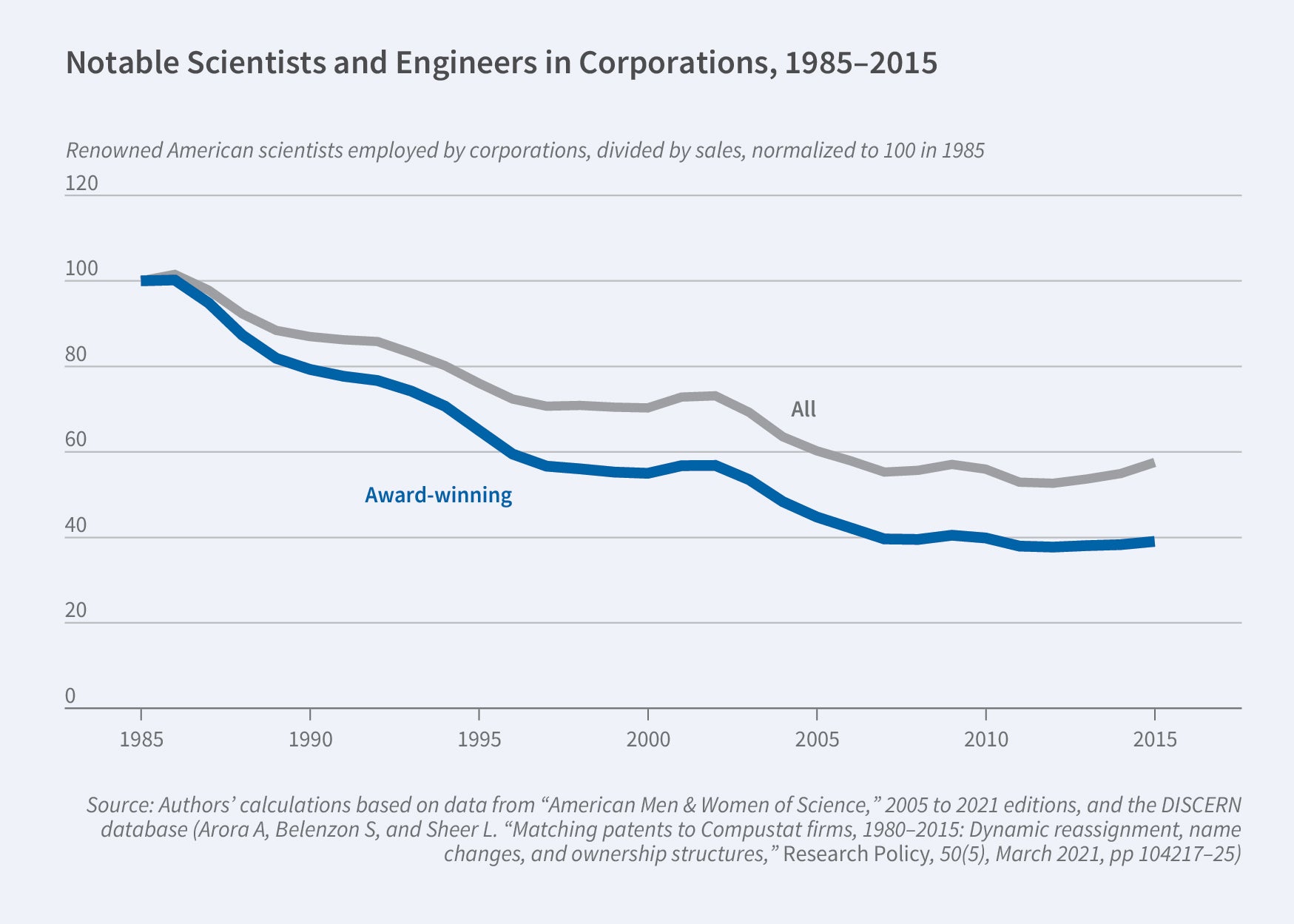

Together with our collaborators, we have studied the evolving specialization of US innovation and the rise and fall of industrial research. Though it still flourishes in fields such as artificial intelligence, the corporate lab’s heyday was from the 1930s until the 1980s. Many leading US firms have withdrawn from scientific research, closing their labs or reorienting them toward applications rather than basic science.1 [Figures 1 and 2]

In the 1960s, DuPont scientists published more articles in the Journal of the American Chemical Society than MIT and Caltech researchers combined. But by the 1990s, the company had reduced its research focus. The number of scientific articles published by DuPont scientists fell from 749 in 1994 to 245 in 2015, while its US patents more than doubled, from around 1,600 in 1994 to nearly 3,500 in 2012. In 2016, DuPont’s Central Research & Development organization was merged with the company’s engineering division. Consistent with this, National Science Foundation data show that the share of basic and applied research in total business R&D expenditures in the United States fell from about 30 percent in 1985 to less than 20 percent in 2015. Simply put, corporate R&D became less “R” and more “D.”2

The Rise of Industrial Research

The leading US companies of the 1870s and 1880s largely relied on external inventions. They acquired inventions in an active market for technology.3 Large companies established labs to evaluate the quality of external inventions and other inputs, test materials, control quality, and troubleshoot production-related issues.4 By World War I, some leading firms recognized they could no longer rely on borrowed technologies or individual inventors. Invention was reliant on scientific knowledge, but university research was limited. General Electric, AT&T, DuPont, and Eastman Kodak led the way by investing in scientific research to fill the gap, and the US corporate lab emerged.

Using newly developed firm-level data from the 1920s and 1930s, we show that the companies most inclined to invest were those using frontier technology in fields where US university research lagged, such as electronics, physics, and polymer chemistry.5 In ongoing work, we are examining the different ways the expansion of university research affects private research, including through production of new scientific knowledge, new human capital, and university inventions available through licensing and university spinoffs.6

Corporate scientific research paid off in breakthrough innovations and high market valuations. DuPont, initially a producer of explosives, lacquers, and rayon, invested in development of polymer chemistry, which became the basis for new products, most notably nylon and polyester. It helped that DuPont had ample resources to develop and commercialize these products and faced little competition. Many labs belonged to large companies operating in concentrated industries, which helped insulate them against spillovers.

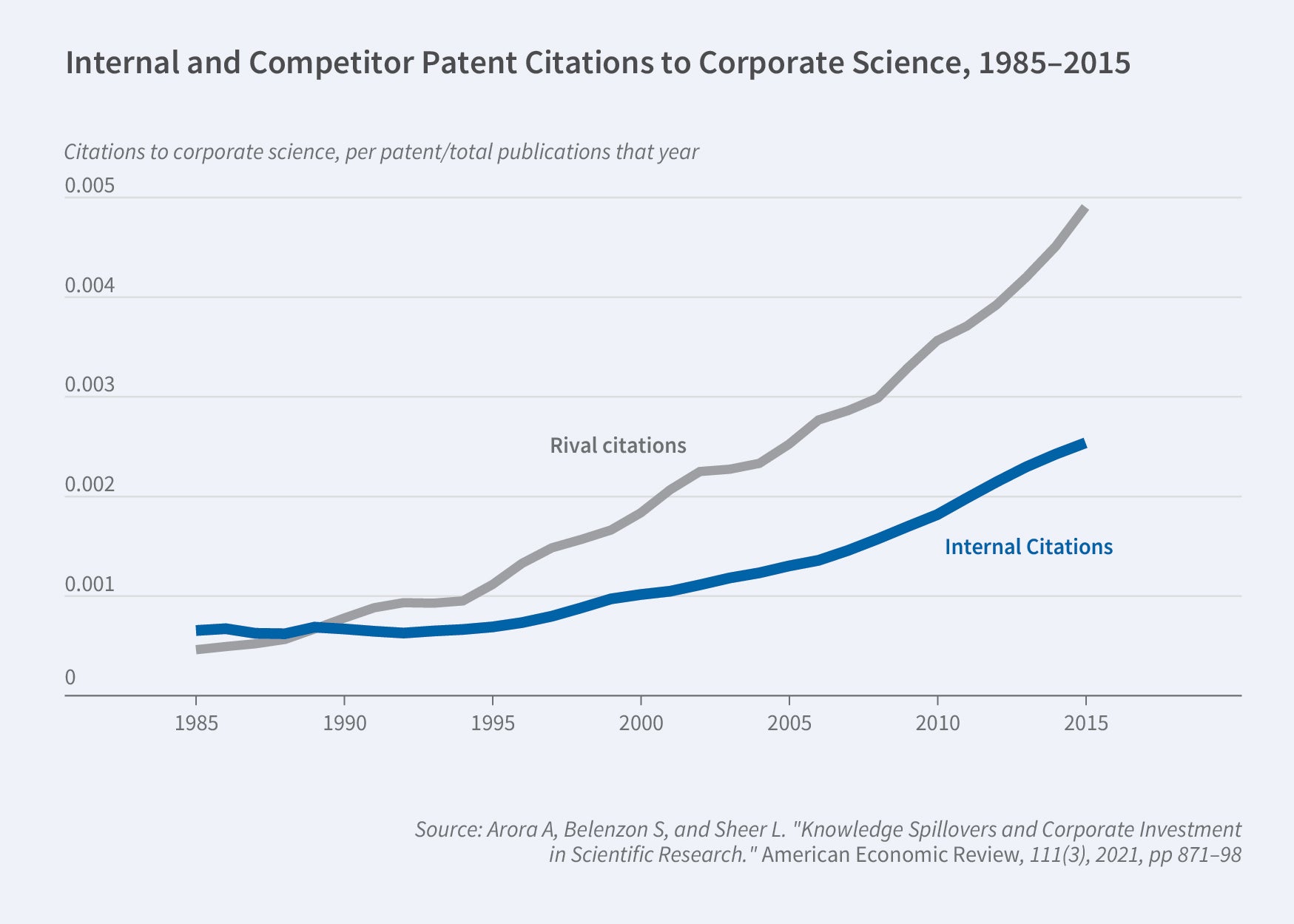

Research is typically disclosed in scientific publications, and hence upstream research is more likely than downstream development to result in knowledge spillovers. In work with Lia Sheer, we show that corporate investment in research trades off the cost of spillovers to rivals against the benefits to the discovering firm of the use of science in its own inventions.7 From 1985 through 2015, spillovers to rivals appear to have increased faster than internal benefits, pointing to one possible reason for the decline of industrial research. [Figure 3] If firms invest in scientific research not only as a perk for talented inventors with a taste for science or as a signal to investors, regulators, or customers, but also as an input to their own inventions, then protection for inventions would encourage investment in research. We find that, consistent with this, weakening patent protection for inventions tied to corporate research reduces follow-on investment in that research stream.8

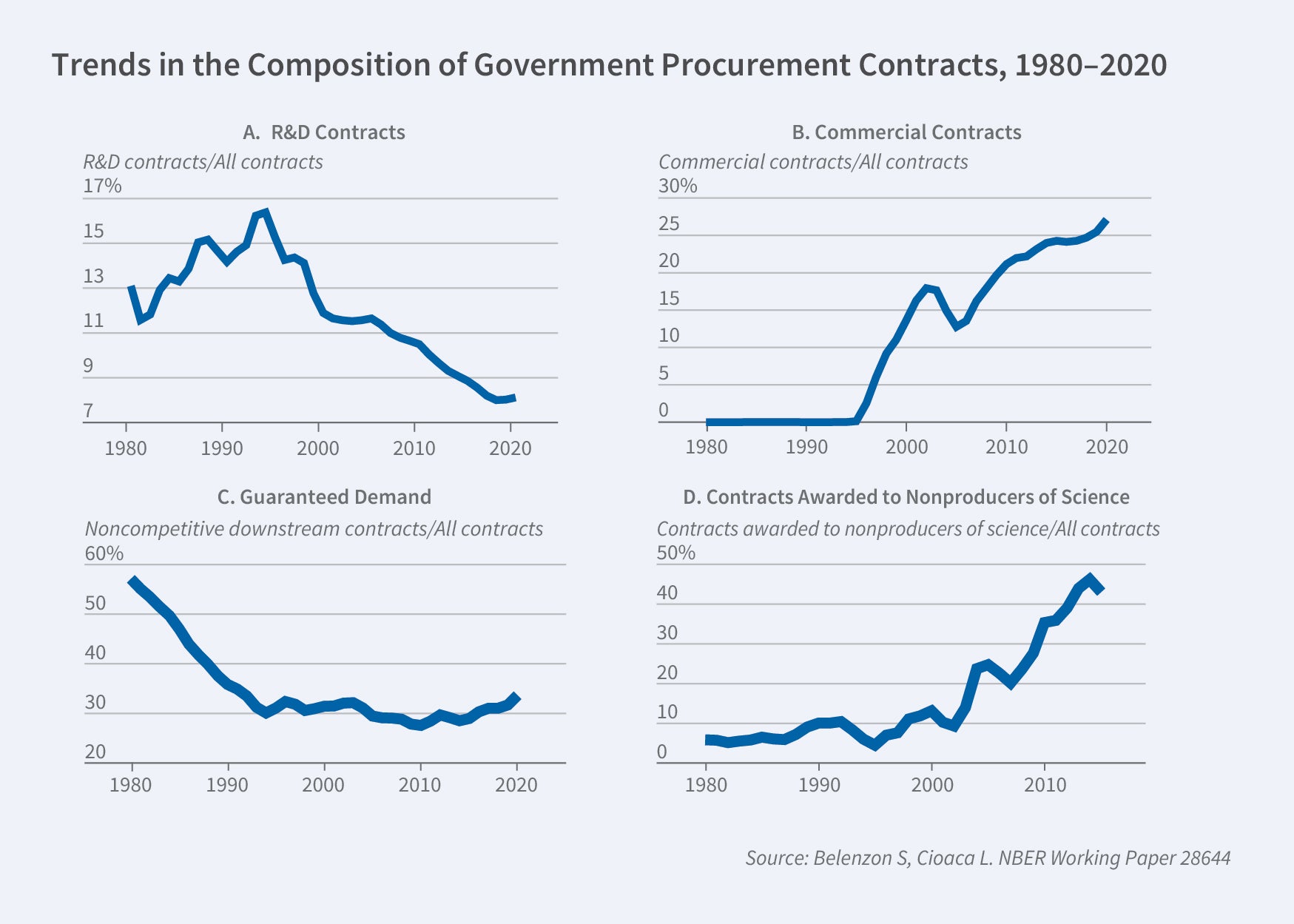

Knowledge spillovers have tended to focus discussions of innovation policy on government support for research, neglecting the potential role of procurement policies. Though the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine was based on years of federally funded research, federal procurement contracts were vital to the final stages of vaccine development. Belenzon and Larisa Cioaca document changes in government procurement policies that may have contributed to the decline in corporate science.9

In addition to funding R&D activities directly, government procurement provides incentives to businesses to invest in R&D by rewarding firms that demonstrate technological superiority in R&D races with downstream procurement contracts. Such “guaranteed demand” was particularly popular during the Cold War (1948–89) but has since diminished. R&D contracts are increasingly decoupled from downstream procurement. [Figure 4] Beginning in the 1980s, the rise of Japan and the end of the Cold War shifted attention away from national security and toward innovations with commercial applications. The growing use of full and open competition in procurement contracting reduced the government’s ability to take the risk out of upstream corporate R&D investments.

American Innovation and the Loss of Corporate Research

Corporate research projects are difficult to replicate in universities and startups: they are larger in scale, combine scientific and engineering disciplines, and are mission oriented. The synergy between science and its application finds its natural expression in industrial research. Significant discoveries are often made while solving specific problems. Louis Pasteur, in studying how to prevent wine from spoiling, developed the germ theory of fermentation as well as the technique of pasteurization. His discovery, in addition to being an extremely valuable industrial innovation, led to the modern sciences of bacteriology, immunology, and microbiology, and to the development of vaccines.

Close collaboration between science and engineering is much easier inside an industrial lab. The Google Translate project is a case in point. Google’s software engineers converted the code created by its computer scientists into the company’s TensorFlow language, hardware engineers modified semiconductor chips originally custom built by Google for neural networks, and database engineers dealt with the copious amounts of data required by the algorithms.

The machine translation example also highlights the multidisciplinary nature of mission-oriented research. The transistor, for instance, would not have been possible without the interdisciplinary efforts of physicists, metallurgists, and chemists at Bell Labs. Metallurgists at the firm had become experienced in purifying and doping semiconductors while manufacturing back-voltage rectifiers for radars during World War II. Bell metallurgist Henry Theurer later developed methods for processing germanium crystals to impurity levels as low as one part per 10 billion. It was also at Bell Labs that Gordon Teal and Ernest Buehler’s crystal “pulling” method for fabricating the positive-negative junctions in silicon rods was developed, as was W. G. Pfann’s “zone refining.”10 William Shockley’s transistor would not have been commercially successful without both of these in-house achievements in material sciences.

An innovation system relying on venture-capital-funded startups may create other kinds of gaps as well. For instance, as Josh Lerner and Ramana Nanda argue, venture investment is narrowly focused on software, digital products, and biotech, neglecting “deep-tech” sectors such as semiconductors and hardware, materials, and clean energy.11 It may well be that startups trying to develop science-based innovations in such sectors are unattractive investments — they can capture only a small share of the value they create because of their weak bargaining position vis-à-vis potential acquirers.12 Their bargaining position is worse if the decline of corporate research results in fewer potential acquirers.

Corporate labs, which were once the hub of the innovation ecosystem in America, have given way to universities and startups. Though the new specialized system offers many benefits, it may also leave important gaps. Startups are less likely to succeed in pulling off large-scale or multidisciplinary innovations. Sectors where both scientific research and technical and commercial development are intertwined are more likely to be neglected by venture capitalists. These gaps may lower the social return to investment in scientific research.

Endnotes

“The Decline of Science in Corporate R&D,” Arora A, Belenzon S, Patacconi A. Strategic Management Journal 39(1), January 2018, pp. 3–32.

“The Changing Structure of American Innovation: Some Cautionary Remarks for Economic Growth,” Arora A, Belenzon S, Patacconi A, Suh J. Innovation Policy and the Economy 20, 2020, pp. 39–93.

“Inventors, Firms, and the Market for Technology in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries,” Lamoreaux N, Sokoloff K. In Learning by Doing in Markets, Firms, and Countries, Lamoreaux N, Raff D, Temin P, editors pp. 19–60. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

"Paths of Innovation: Technological Change in 20th-Century America, Mowery D, Rosenberg N. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

“The Rise of Scientific Research in Corporate America,” Arora A, Belenzon S, Kosenko K, Suh J, Yafeh Y. NBER Working Paper 29260, November 2022.

“Knowledge Spillovers and Corporate Investment in Scientific Research,” Arora A, Belenzon S, Sheer L. American Economic Review 111(3), March 2021, pp. 871–898.

“(When) Does Patent Protection Spur Cumulative Research within Firms?” Arora A, Belenzon S, Marx M, Shvadron D. NBER Working Paper 28880, June 2021.

“Guaranteed Markets and Corporate Scientific Research,” Belenzon S, Cioaca L. NBER Working Paper 28644, January 2023.

“Science Indicators 1980 Report of the National Science Board 1981,” Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1981.

"Venture Capital’s Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn,” Lerner J, Nanda R. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(3), Summer 2020, pp. 237–261.

“Caught in the Middle: The Bias against Startup Innovation with Technical and Commercial Challenges,” Arora A, Fosfuri A, Rønde T. NBER Working Paper 29654, January 2022