Are Larger Cities Losing Their Edge?

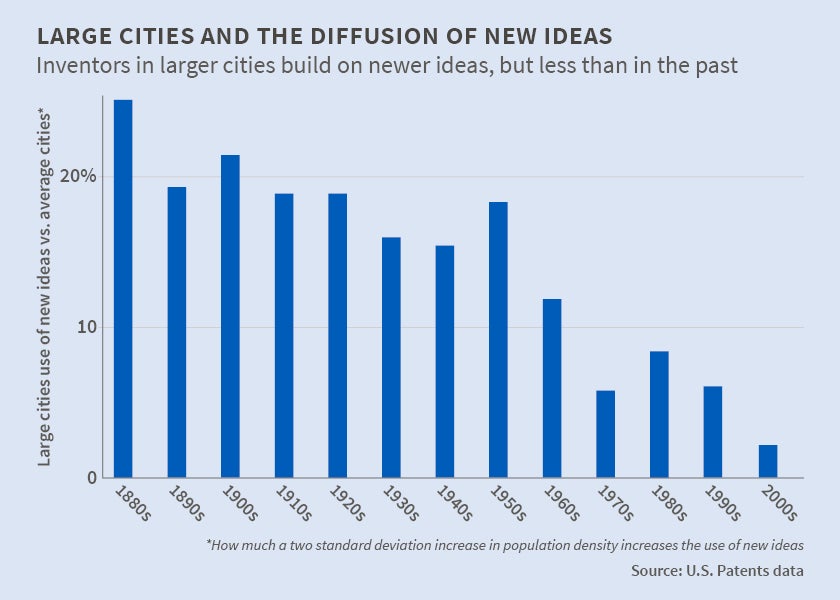

Inventors in densely populated areas relied on newer scientific breakthroughs more than their more-isolated peers until the middle of the 20th century, after which the disparity steadily narrowed.

Nearly a century ago, the eminent economist Alfred Marshall hypothesized that ideas were more likely to germinate into useful inventions in large cities than in smaller ones. Innovators working in close proximity to other creative minds, he argued, had a greater opportunity to learn of the latest advances and to engage in brainstorming.

In Cities and Ideas (NBER Working Paper No. 20921), Mikko Packalen and Jay Bhattacharya test this conjecture. They study U.S. patents granted between 1836 and 2010, and calculate the population density per square mile where the inventor resided. This enables them to distinguish patents that were developed in urban areas from those that were developed elsewhere. They also identify the key concepts that each patent refers to, which in turn reflect the scientific or engineering foundation on which the patent is based. For each concept, they search the entire patent database to determine the date on which this concept was first mentioned. This makes it possible to classify patents based on the age of their scientific background. A patent for which the key concept first appears in the patent database just one year before the patent was filed is based on "younger" innovations than a patent for which the key concept has been referenced in patents for several decades.

The authors find that, on average, patents that were filed by inventors in densely populated areas relied on newer science than patents filed by their more-isolated peers until the middle of the 20th century. In 1900, for example, a two standard deviation increase in the population density of an inventor's home town was associated with a 20 percent increase in the probability that the patent would be one that relied on the latest scientific advances. The study defines a patent as using "latest advances" if the age of the patent's key concept falls in the youngest 5 percent of the concept age distribution.

The tendency for patents filed by inventors in densely populated areas to rely on newer scientific breakthroughs has waned in recent decades. There was a decline between the 1950s and the 1970s, and, after an uptick in the 1980s, a decline again in the 1990s and 2000s. "Taken together," the authors write, "our results suggest that in the late 20th century agglomeration has become less important to innovation both in absolute terms and relative to other factors—like collaboration—that predict the use of newer ideas."

The authors hypothesize that the recent decline in the difference in use of newer breakthroughs between more- and less-densely populated areas may be due to the spread of new communication technologies that have made new ideas available more readily to all. For example, with the emergence of the Internet, virtual communities may be erasing the advantage of physical proximity, and those in less-urban areas may be able to participate as effectively as those in larger cities in debating the merits and application of new ideas.

— Steve Maas