Fewer H-1B Visas Did Not Mean More Employment for Natives

Changes in H-1B visa availability instituted beginning in 2004 resulted in a greater concentration of India-born workers in computer-related fields.

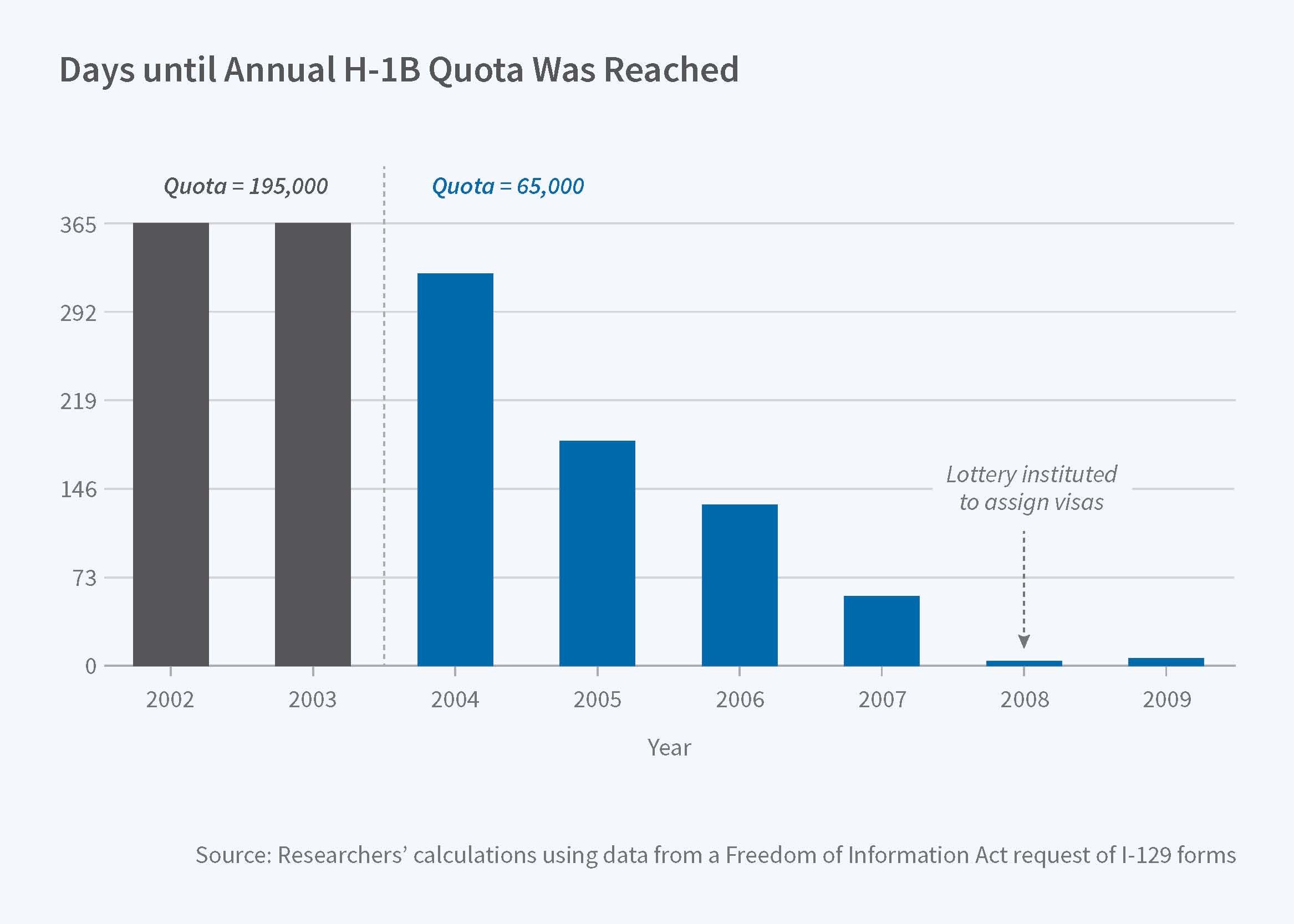

In response to concerns that foreign workers were taking jobs from Americans, especially in high-technology fields, Congress declined to renew previous temporary increases, which reduced the annual quota on new H-1B visas from 195,000 to 65,000, beginning with fiscal year 2004. A study by Anna Maria Mayda, Francesc Ortega, Giovanni Peri, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber, based on data for the fiscal years 2002-09, finds that the reduced cap did not increase the hiring of U.S. workers.

In The Effect of the H-1B Quota on Employment and Selection of Foreign-Born Labor (NBER Working Paper No. 23902), the researchers examine data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request to present the first assessment of the consequences of the cap reduction on various sectors of the skilled labor force.

The H-1B program, which was launched in 1990, has provided foreign-born, college-educated professionals their main entry point into the U.S. market. As much as half the growth in America's college-educated science, technology, engineering and mathematics workforce in subsequent decades can be attributed to H-1B workers.

Since the cap was tightened in 2004, firms hired between 20 and 50 percent fewer new H-1B workers than they might have hired had it remained at 195,000 visas per year. The researchers find, however, that the reduced pool of foreign workers did not lead firms to hire more Americans, and conclude that this suggests "low substitutability between native-born and H-1B workers in the same skill groups." The cap only applies to for-profit companies, not to new employees of educational institutions or nonprofit research institutions.

The researchers also find that the quota reduction resulted in changes to the composition of new visa holders and the companies that hired them. Employment losses were concentrated at the lowest and highest ends of the wage scale, leading H-1B workers to become more concentrated among workers with mid-level skills. "The binding H-1B cap reduced the number of workers who were likely to have been among the most talented and productive foreign individuals seeking U.S. employment." Yet these are just the workers who might have contributed technological advances benefiting the entire economy.

The cap led to an increased concentration of India-born workers in computer-related fields. The paper posits that Indians had a leg up on other foreign workers because of long-established labor networks in the software and semiconductor industries.

On the employer side, the lower cap favored larger firms with greater experience navigating the bureaucracy of the visa program and with in-house legal teams that could handle the paperwork. This proved especially advantageous in fiscal years 2008 and 2009, when demand for visas was so high that the number of applications exceeded the quota level within the first week and the government resorted to a computerized random lottery system to allocate them. Smaller firms simply could not afford to spend money applying for visas when they were not sure whether they would obtain one.

— Steve Maas