The Economic Costs of Noise Pollution from Aircraft and Traffic

In Planes Overhead: How Airplane Noise Impacts Home Values (NBER Working Paper 34431), Florian Allroggen, R. John Hansman, Christopher R. Knittel, Jing Li, Xibo Wan, and Juju Wang examine how changes in aircraft noise exposure affect residential property values near Boston Logan International, Chicago O'Hare International, and Seattle-Tacoma International airports. The researchers leverage the Federal Aviation Administration's rollout of Performance-Based Navigation procedures beginning in 2006, which replaced conventional radar-based navigation with satellite-guided routing, creating more concentrated flight paths that altered noise exposure in ways residents could not anticipate. They also utilize runway reconfigurations associated with airport capacity expansions, which changed takeoff and landing patterns.

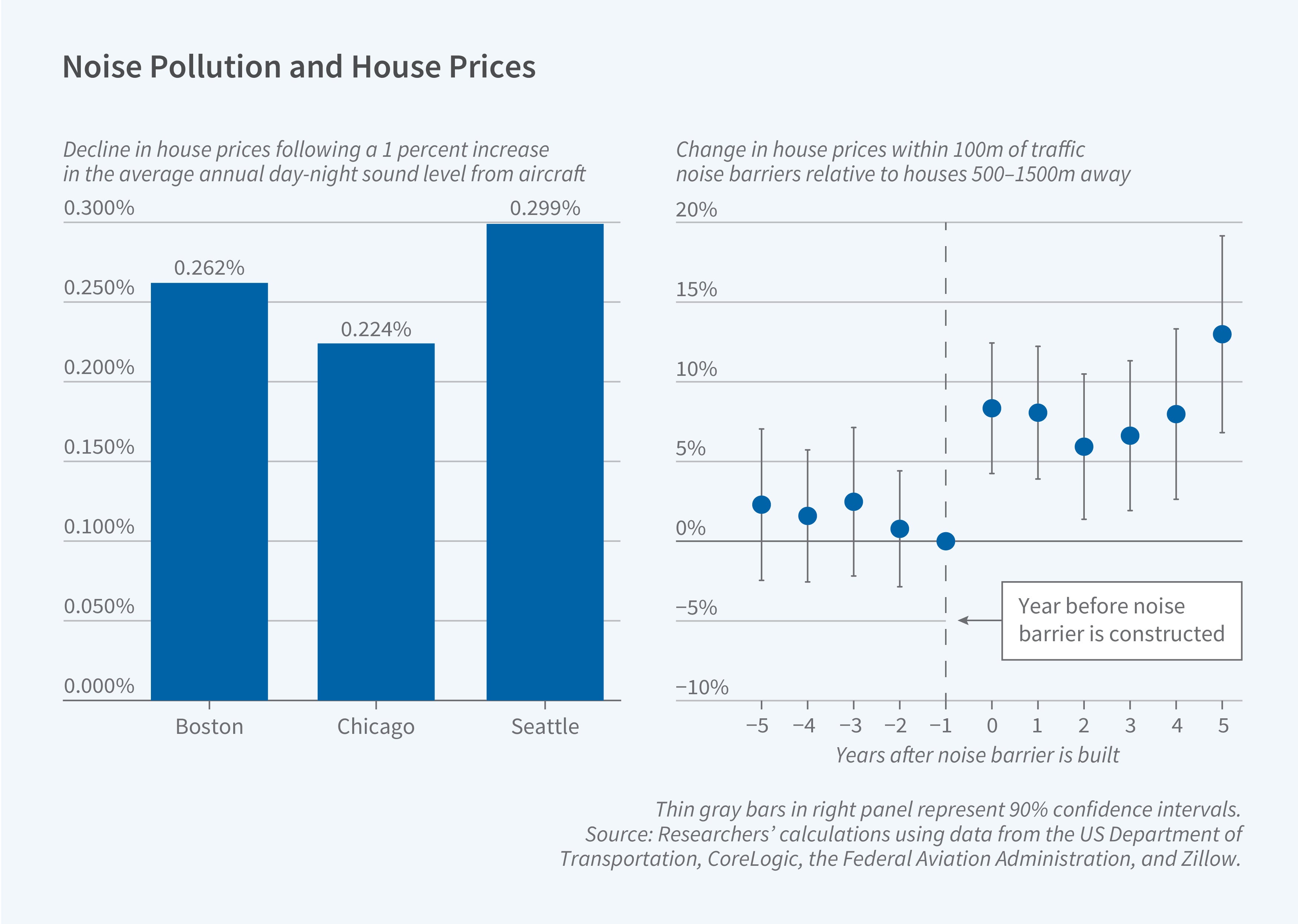

The researchers combine high-resolution flight trajectory data with detailed noise propagation modeling to create precise measurements of aircraft noise. They merge this information with geocoded housing transaction records from 2011 to 2016, yielding over 85,000 transactions across the three cities. They find house price declines of between 0.6 and 1.0 percent per one-decibel increase in day-night average sound level. On an annual basis, the average willingness to pay for a one-decibel reduction in sound levels is approximately $152 in Boston, $104 in Chicago, and $221 in Seattle. Higher household income in a locality is associated with a higher willingness to pay for noise reduction, and non-White households appear to have a lower willingness to pay. These findings suggest that aircraft noise externalities have meaningful distributional consequences.

A second study, The Traffic Noise Externality: Costs, Incidence and Policy Implications (NBER Working Paper 34298) by Enrico Moretti and Harrison Wheeler, examines traffic noise. The researchers use an approach based on the construction of noise barriers alongside highways and analyze transaction-level housing data from CoreLogic covering 1990 to 2022. The main empirical strategy compares changes in house prices after barrier construction for properties located 0–500 meters from traffic with changes for properties 500–1,500 meters away. There is a rapid decline in noise intensity with distance, so the barriers have a much smaller effect on noise levels for the second than the first group of properties.

In the five years following barrier construction, properties within 100 meters experience an increase in value of 6.8 percent, on average. The effect diminishes with distance from the barrier. For distances greater than 400 meters, the researchers find no statistically significant effect of barrier construction. The study also exploits variation in the expected noise reduction achieved by different barriers and finds that price effects increase with the degree of noise reduction. These estimates yield a willingness to pay of approximately 0.94 percent of local median income per decibel of noise reduction. Boston has the highest per-capita costs at $1,310 per resident, more than 13 times Atlanta's $100 per resident.

A 10 percent decrease in a tract's median family income is associated with 1 percent higher per-capita noise costs, with low-income households and Black residents overrepresented in high-noise areas.

The researchers extrapolate their results to estimate that traffic noise imposes an aggregate economic burden of $110 billion on the United States, with low-income and minority households bearing a disproportionate share. They also estimate that the Pigouvian tax on noise pollution would be $974 per vehicle over its lifetime and project that universal adoption of electric vehicles could generate noise reduction benefits of $77.3 billion, concentrated among low-income families in dense urban areas.

Harrison Wheeler acknowledges support from the TD Management Data and Analytics Lab and Enrico Moretti acknowledges support from the Berkeley Opportunity Lab.

Florian Allroggen, R. John Hansman, Christopher R. Knittel, Jing Li, Xibo Wan, and Juju Wang acknowledge support from the US Federal Aviation Administration Office of Environment and Energy through The Center of Excellence for Alternative Jet Fuels and Environment (ASCENT), Project 72, through FAA Award Number 13-C-AJFE-MIT under the supervision of Adam Scholten and Joseph Dipardo.