Private Sector Responses to Public Transit Initiatives

Today, 55 percent of the world’s population lives in cities, a share expected to reach 70 percent by 2050. Much of this growth will occur in developing countries, which are investing heavily in mass transit to expand access to jobs and services. Private minibuses already dominate many urban markets: in Lagos—the largest city in sub-Saharan Africa—minibuses accounted for 62 percent of all trips in 2009, versus just 5 percent for public buses. New public transit investments may therefore impact commuters both directly and indirectly if private operators adjust their routes, frequencies, or fares in response.

Starting in 2020, the Lagos government launched 64 new public bus routes served by 820 large, modern buses. These public buses can carry up to 70 passengers each, compared with 14 in the most common type of private minibus. In Public and Private Transit: Evidence from Lagos (NBER Working Paper 33899), Daniel Björkegren, Alice Duhaut, Geetika Nagpal, and Nick Tsivanidis examine how Lagos’s existing private minibus transit system responded to competition from new public bus routes.

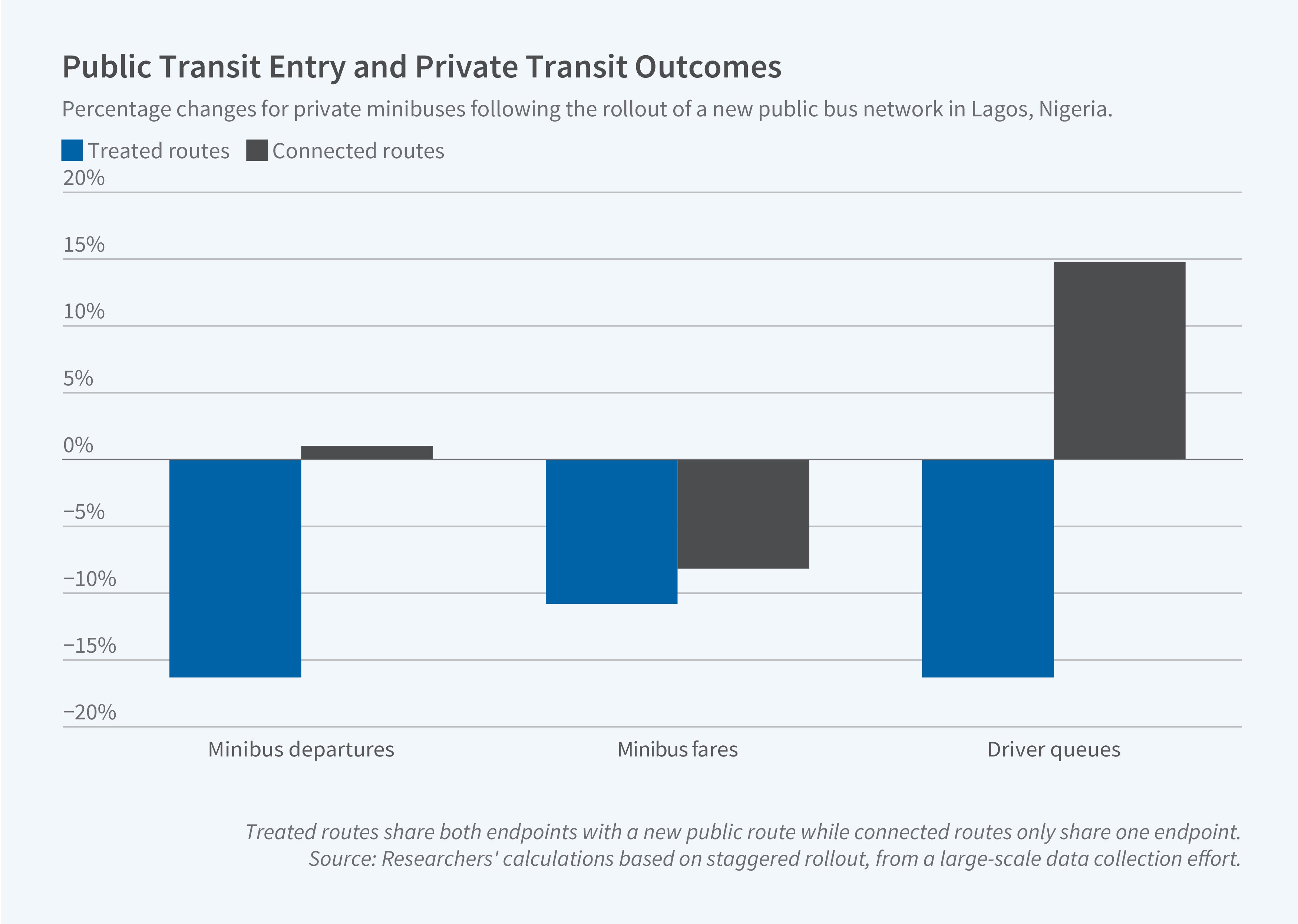

When Lagos, Nigeria, introduced public buses, private minibus departures declined by 16 percent on competing routes while fares fell across the network.

From late 2020 to the end of 2021, the researchers made half-hourly observations of private minibuses’ departures, fares, and driver queues during morning peak, afternoon peak, and midday off-peak periods at terminals covering 278 routes and 79 bus stops. They classified routes as "treated" (sharing both endpoints with a new public route), "connected" (sharing one endpoint), or "control" (sharing neither endpoint). The researchers also mapped the private system by hiring a firm to send out enumerators with GPS trackers to identify and ride existing private minibus routes, uncovering a transit network of 759 routes spanning almost 30,000 kilometers (18,641 miles).

The private minibus network is dense and regulated by drivers’ associations that set fares, collect fees, and impose order on the industry. Within terminals, minibus drivers queue up to serve a particular route. When the minibus at the head of the line fills up, it starts its route, and people begin boarding the next bus in line. There are typically between 7 and 9 departures per hour.

The new public buses depart much less frequently, with 0.5–1 departure per hour on average. When the government added public buses to an existing private transit route, minibus fares fell between 5 and 10 percent, and minibus departure frequencies fell by 16 percent. Because public buses board at different places than private buses, commuters faced longer waits regardless of how they traveled. Drivers on treated routes experienced a drop in profits and were more likely to switch to other routes: queues on treated routes shortened by about 16 percent, and queues on connected routes increased. These spillover effects also reduced prices on connected routes. The new system did not affect congestion.

The researchers estimate that riders’ disutility of waiting, a key determinant of the welfare consequences of transportation reforms, was approximately $1.42 per hour—about 2.9 times the riders’ average wage. The direct benefit of new public buses increased consumer surplus by an estimated $1.33 million per month, but the private sector response, resulting in longer wait times for private transit, reduced this surplus by $0.26 million. Lower prices for minibus rides raised consumer surplus by $0.41 million, so, on balance, the private sector response raised commuter welfare. While these gains were spread over a million commuters, the estimated 11,000 minibus drivers lost $0.75 million per month—about half of the commuter gains.

- Linda Gorman

This work was supported by the World Bank’s research support budget, the World Bank Knowledge for Change Program, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Partnerships (DG INTPA) and the UK Department for International Development under the World Bank’s Umbrella Facility for Impact Evaluation, the Clausen Center at UC Berkeley, the International Growth Centre, the J-PAL King Climate Action Initiative, the Brown University Seed Award, the Weiss Fund, and the Structural Transformation and Economic Growth Initiative at CEPR.