Expelling Japanese Americans Lowered US Farm Productivity

The expulsion of Japanese Americans from western states during World War II upended nearly 120,000 lives, including those of nearly 22,000 agricultural workers, and set back farming in affected regions for several decades. Citing security concerns in the wake of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the US government in spring 1942 declared that all individuals of Japanese ancestry, regardless of citizenship status, were subject to mandatory removal from all of California and parts of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona. Most were eventually resettled in internment camps. At the end of the war, fewer than half of the internees returned to their original states, and fewer still reclaimed their farms or returned to agriculture.

In How the 1942 Japanese Exclusion Impacted US Agriculture (NBER Working Paper 33971), Peter Zhixian Lin and Giovanni Peri show that Japanese Americans made up a disproportionate number of agricultural workers in the counties affected by the expulsion order. Drawing on county-level data from the Population Census and the US Census of Agriculture in the years between 1925 and 1940, they show that Japanese Americans tended to be better educated and to possess greater expertise than their non-Japanese counterparts. They grew more profitable crops, such as fruit and vegetables, and were more likely to adopt the latest innovations in machinery, fertilizer, and other farming techniques.

A 1 percent reduction in the share of Japanese American farmers in a county’s farm labor force caused a 12 percent decline in agricultural growth.

In the 1940 Census, 42 percent of working-age Japanese Americans (age 14 and up) in the exclusion zone counties held jobs in agriculture, compared with 11 percent of the general population. Thirty-one percent of Japanese farm workers had finished high school, compared with only 12 percent of their White counterparts. The average land value of Japanese farms was $246 per acre, compared with $40 for non-Japanese farms.

As a result of the evacuation orders, affected counties suffered an agricultural brain drain. Slower to mechanize and adopt innovative technologies and fertilizers, these counties fell behind in farm performance. Each percentage point reduction in the number of Japanese farm workers was associated with a 23 percent decrease in fruit and vegetable sales in the post-1942 period. This negative effect stems from slower growth of farm productivity and farm value rather than from fewer farms.

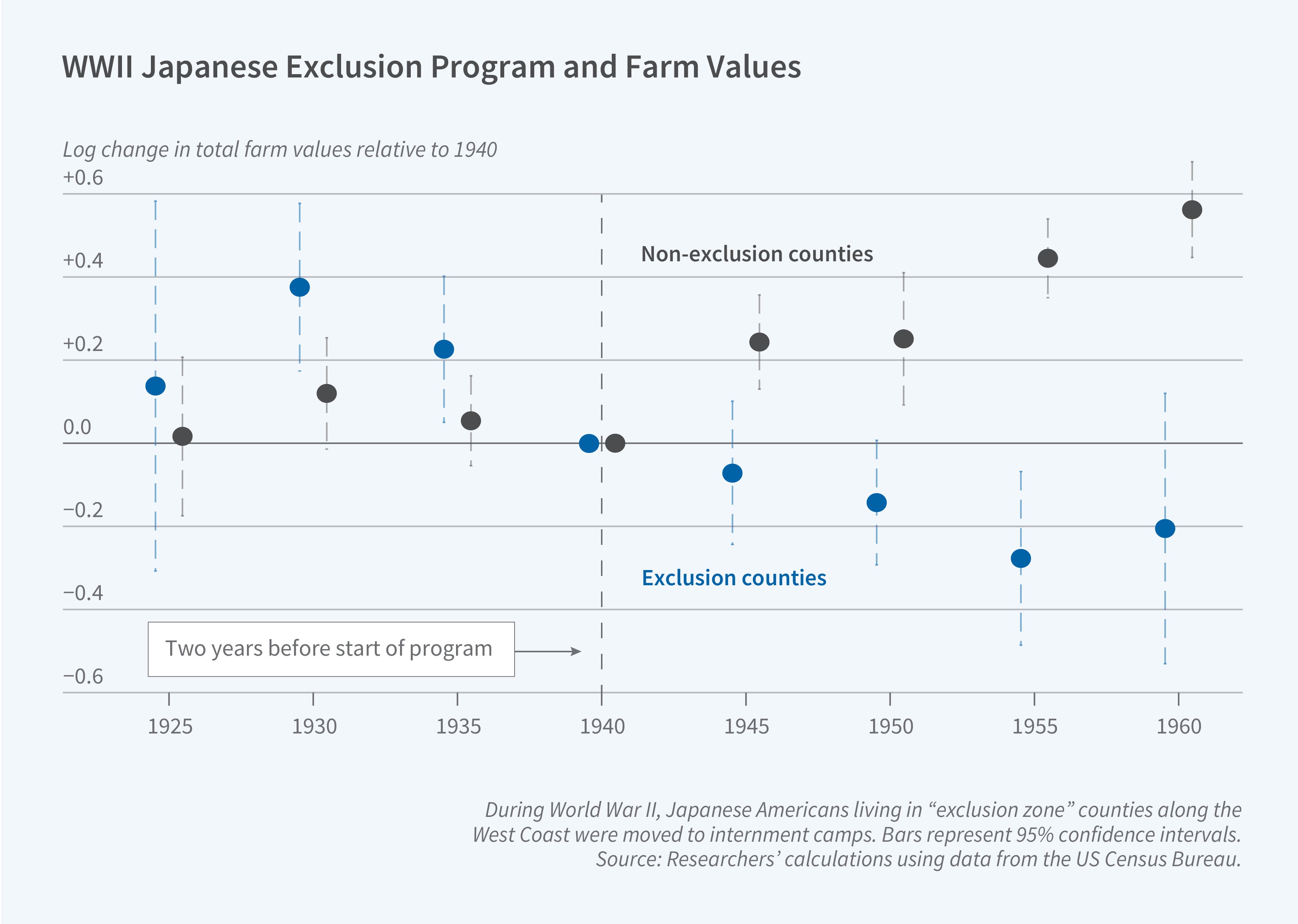

Meanwhile, counties outside the exclusion zone that had larger shares of Japanese farmers as of the 1940 Census grew relatively faster in the postwar years. For every percentage point increase in Japanese farm worker share, non-exclusion counties experienced nearly 9 percent higher total growth in farm value over the 1945–60 period. Counties from which Japanese workers were expelled experienced 12 percent slower growth in farm value for each percentage point reduction in the share of Japanese Americans among farm workers.

Expelling Japanese farmers reverberated beyond the agriculture sector. The researchers conclude that “the loss of these skilled farmers hindered technological adoption, creating lasting negative effects on both agricultural performance and broader local economic development.”

- Steve Maas