China's Expansion of Drug Insurance Increased Access While Containing Costs

China's National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) reform, which affected over 1 billion people, was one of the world's largest pharmaceutical insurance policy experiments. Prior to 2016, China's universal health insurance excluded innovative drugs, forcing patients to pay high out-of-pocket prices for some life-saving treatments. The reform expanded access to these drugs and also negotiated prices centrally.

In A Double Dose of Reform: Insurance and Centralized Negotiation in Drug Markets (NBER Working Paper 33832), Panle Jia Barwick, Ashley T. Swanson, and Tianli Xia examine the economic and welfare implications of this reform. They analyze comprehensive drug sales data from SinoHealth for the 2017–23 period along with information on negotiation outcomes, clinical trials, and provincial demographics. They focus their analysis on cancer drugs, which account for two-thirds of revenues among negotiated drugs.

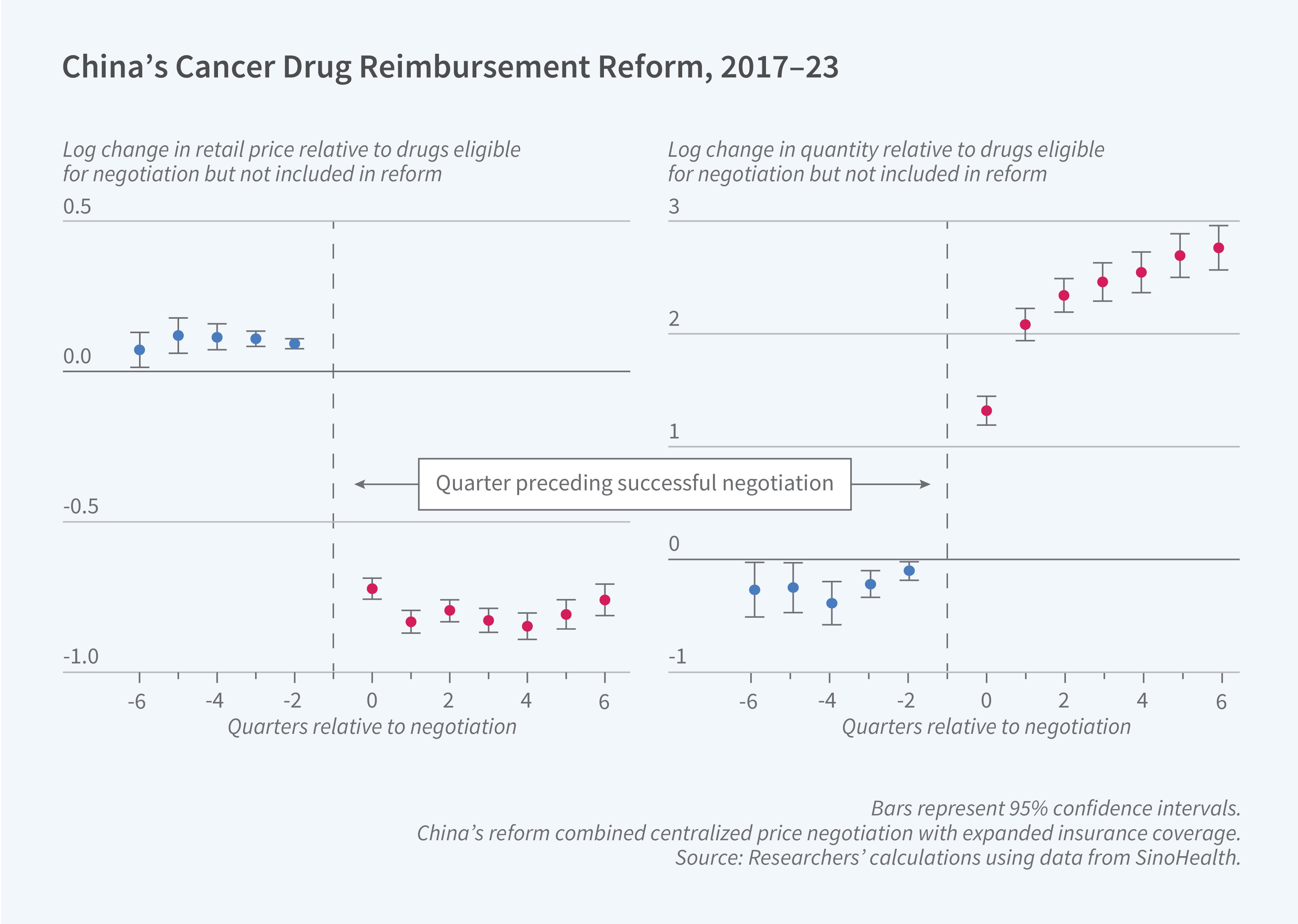

China’s pharmaceutical insurance reform, which combined centralized price negotiation with insurance expansion, reduced cancer drug prices by 57 percent while increasing access nearly tenfold.

The researchers find that the reform reduced retail prices by 57 percent for successfully negotiated cancer drugs, while about 36 percent of negotiations failed. Out-of-pocket drug costs fell by 86 percent, and drug utilization increased by 350 percent. Higher-quality drugs were more likely to be successfully negotiated. Firms retained substantial bargaining power, capturing about two-thirds of the surplus from negotiations. The data suggest that when drug prices increase by 1 percent, the average patient reduces their drug purchases by 1.6 percent. This price sensitivity is stronger for poorer patients: for households in the bottom quarter of incomes, drug purchases fall by 1.9 percent, compared with 1.3 percent for those in the top quarter of incomes.

The researchers estimate that innovative cancer drugs successfully negotiated between 2017 and 2022 generated ¥40 billion ($5.6 billion) in annual consumer surplus gains and increased survival by 900,000 life-years among Chinese cancer patients each year. They also estimate that expansion alone would have reduced out-of-pocket prices but resulted in sharp retail price increases as firms responded to reduced consumer price sensitivity. Price negotiation without insurance expansion would have had no impact, as firms would have lacked incentives to participate.

The researchers analyze several alternative policy designs and estimate that market-access negotiation—where drugs are excluded from the Chinese market entirely if negotiations fail—could raise social surplus by as much as 19 percent if it were paired with optimal coinsurance design. They also find that centralized negotiation benefits most provinces compared to decentralized bargaining, although the wealthiest regions would prefer provincial-level negotiations. Their estimates imply that utilitarian social surplus is maximized with a moderately regressive insurance schedule, as demand expansion from high-income households increases the government’s bargaining leverage, which ultimately benefits all patients through expanded drug coverage and lower prices.

Support for this research was provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.