Unpacking the Union Wage Premium

There is broad agreement that the wages of unionized workers are higher than those of workers who are not union members. There is less consensus, however, on the source of this wage premium and in particular the extent to which it reflects actions by unions rather than differences between union members and other workers or unionized and other firms. In Why Do Union Jobs Pay More? New Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data (NBER Working Paper 33740), Pierre-Loup Beauregard, Thomas Lemieux, Derek Messacar, and Raffaele Saggio analyze the Canadian Business Employee Analytical Microdata for the period 2001 to 2019 to provide new evidence on this question.

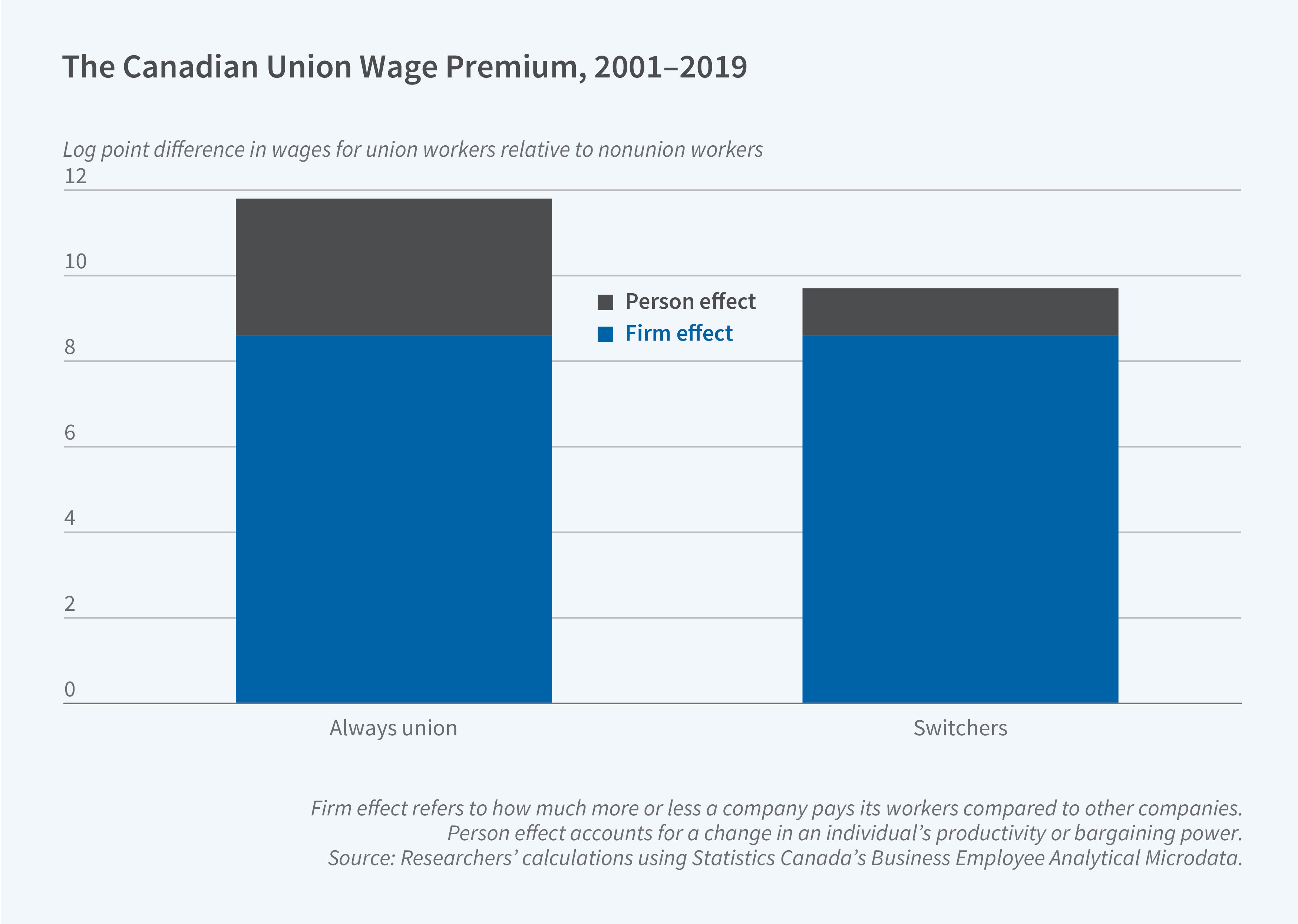

In Canada, about 60 percent of the union wage premium comes from unions' ability to negotiate higher wages, while the balance is from unionized firms being more productive than their nonunionized counterparts.

They find that the higher wages enjoyed by unionized workers can be traced to two primary factors. One is rent extraction, the capacity of unions to negotiate higher wages for their workers on account of their collective role, and the other is firm selection. Unionized firms are more productive, on average, than nonunionized firms, and pay reflects this higher value added per worker. The researchers estimate that rent extraction accounts for about 60 percent of the premium and that selection explains most of the rest.

The study leverages job switchers—workers who move between union and nonunion jobs—to control for worker characteristics while identifying union effects. Among switchers they find a premium of 9.8 log points, with 8.6 log points induced by unions through firm-level pay policies. When incorporating always-unionized workers (who comprise more than 60 percent of unionized workers), the union premium increases to 11 log points. Always-unionized workers are more likely to be women and have lower education levels—characteristics associated with larger pay gains from unionization.

The data underlying the study identify both firms and workers, which makes it possible to determine whether factors other than unionization explain the wage gap between unionized and other workers. Specifically, the researchers find that after controlling for year effects and worker-age effects, unionized firms pay about 15 percent more than nonunionized firms. When they control for value added per worker, the per-worker average of annual payroll plus net income at each firm, the estimated union premium falls to about 9 log points, or 60 percent of the total premium. This suggests that productivity disparities can account for about 40 percent of the union wage premium.

Unionized firms in the researchers’ sample are about 28 percent more productive than nonunionized firms, and they exhibit less variability in worker pay. Assortative matching, where highly paid employees work for high-pay employers, is only half as large for union jobs as for nonunion jobs. This suggests that the risk of being missorted, for example, being a high-skill worker at a low-pay firm, is greater at unionized than at nonunionized firms. This finding is consistent with past research that found wage compression at unionized firms. Such compression can create a wage floor, which helps low-skill workers, as well as a ceiling, which can hurt higher-skilled workers. The researchers confirm that the benefits of a union job are greatest, on average, for low-skill workers and for workers who spend most or all of their careers in unionized jobs.

- Emma Salomon

The researchers thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for financial support. This research was conducted at the University of British Columbia (UBC), a part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). This service is provided through the support of the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and Statistics Canada, as well as the support of UBC.