Global Value Chains: A Firm Level Approach

Global value chains have come under severe scrutiny in the past few years. Pandemic-era shortages, geopolitical concerns, and new industrial strategies have all revived an old worry: have firms become too dependent on a handful of foreign suppliers and assembly hubs? Should governments use policy tools such as tariffs or subsidies to promote domestic manufacturing employment and capabilities?

The heart of this debate centers around a firm’s decisions about whether and how to participate in global value chains: which countries will supply its components, where should it open assembly plants, and what foreign markets shall it enter to sell its goods?

Our research starts from the premise that the right unit of analysis for understanding this system is not the country or the industry, but the firm. Over the past decade we have studied the firm’s problem from several angles, guided by confidential US firm-level data and by a simple economic mechanism: fixed costs paid at the level of the firm-country pair generate economies of scope that knit together activities that conventional models often examine in isolation.

The Global Sourcing Decision

Our research agenda initially focused on firms’ global input-sourcing decision and emphasized that the ability to import from foreign markets is constrained by the need to incur nontrivial upfront fixed costs to find suitable suppliers, build distributional networks, and understand the institutional aspects of the source country.1 Although fixed costs also feature prominently in workhorse models of exporting, the canonical firm-level export model assumes that a firm’s decision to serve a given market, say France, has no bearing on its decision to sell in a different market, say Japan, because exporting is assumed to leave marginal costs unchanged. Importing is different precisely because it is motivated by the firm’s desire to reduce its marginal cost of production.

As a result, the combination of fixed costs and marginal-cost-reducing benefits from importing induces interdependencies in a firm’s sourcing strategy. Moreover, when comparing countries in terms of how expensive it is to find suppliers, or in other aspects that shape the fixed costs to source from them, against the marginal-cost benefits once such fixed costs have been incurred, there is no clear ranking of countries in terms of their overall input-sourcing appeal. Indeed, using 2007 US import data, we find that countries’ import ranks based on the number of US manufacturing importers differ from their ranks based on the amount of imports by those manufacturing firms. For instance, China might offer the most marginal-cost savings in terms of lower-price inputs, but it may require a higher fixed cost to find a reliable supplier in China relative to other countries.

Our multicountry model of global sourcing shows that whether sourcing decisions are complements or substitutes depends on a simple parametric condition: if demand is relatively elastic and input productivity differences across countries are sufficiently dispersed, then sourcing from one country raises the marginal return to sourcing from another. In this case, optimal sourcing decisions follow a strict hierarchy in which more productive firms source from more countries. These complementarities also amplify existing productivity differences: high-productivity firms disproportionately expand their sourcing networks and grow larger, increasing the skewness in the firm size distribution. In our work, we also develop an iterative algorithm to solve the firm-level extensive margin of sourcing, which, in our framework, is a combinatorial problem of dimensionality two times the number of countries under consideration.

We provide empirical evidence that US firms’ sourcing decisions are indeed complementary using plausibly exogeneous variation in sourcing costs due to China’s 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization. Firms that increased their sourcing from China in response to the shock also increased their imports from other countries, including the US. These results stand in sharp contrast to the assumptions in much of the current policy debate, in which the presumption seems to be that input countries are substitutes for each other so that raising the cost to source from one country will induce firms to source more from others.

Our model implies that new tariffs on US imports from China will raise US manufacturing firms’ costs and reduce aggregate productivity in the sector. Although domestic manufacturing employment will rise, it will do so in smaller, less productive firms and entail higher prices and lower welfare for US consumers.

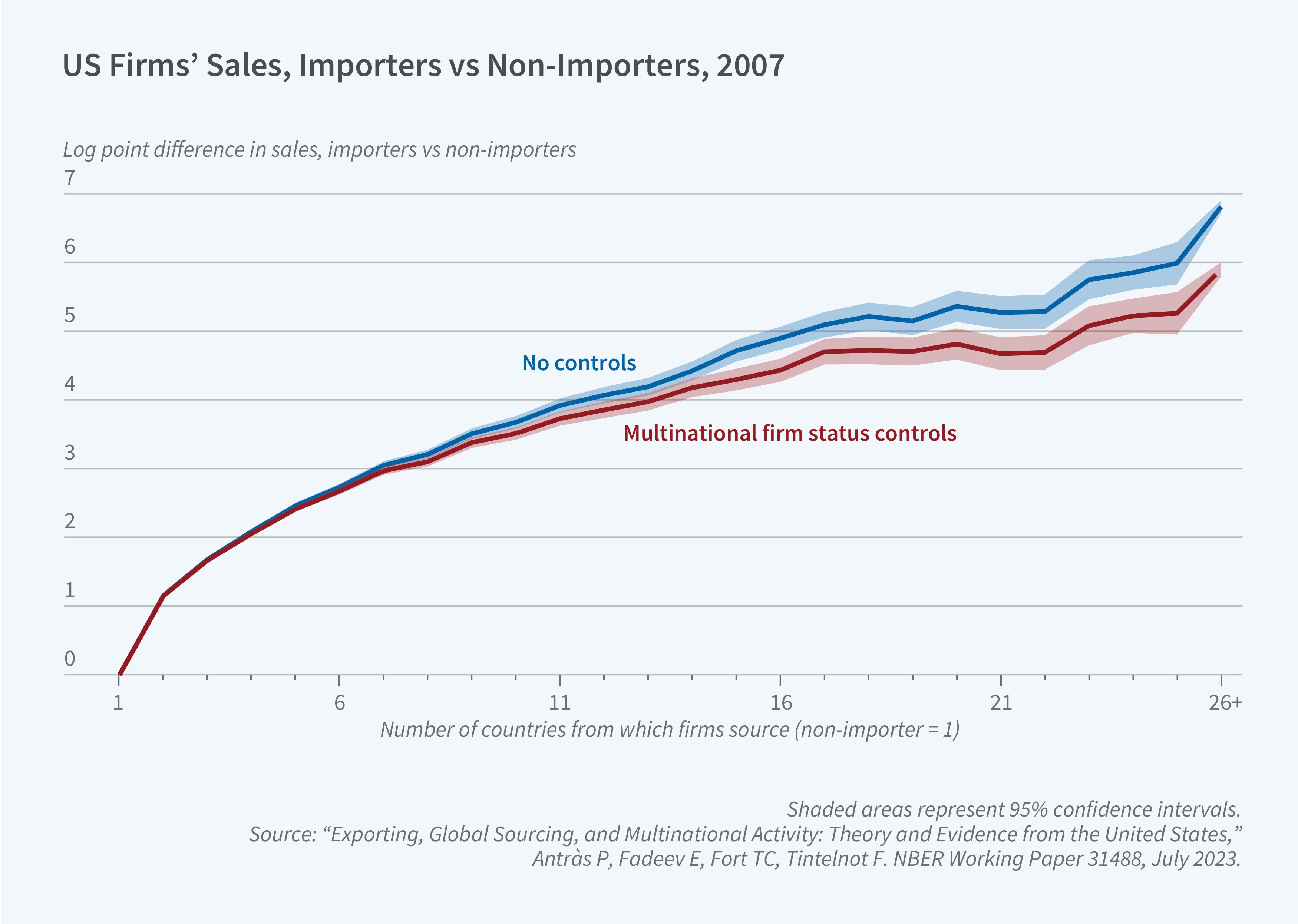

Our microlevel dataset unveils additional interesting facts. The data show a strong, monotonic relationship between firm size and the number of countries from which a firm sources. In 2007, US firms that imported from one country were, on average, more than twice the size of non-importers; those importing from 13 countries were four log points larger, and those sourcing from 25 or more countries were over six log points larger (see Figure 1). This size gradient can be interpreted as supporting the relevance of fixed costs of importing, which naturally limit the profitability of importing for relatively small firms. But this pattern also supports the complementarity forces in our framework: more productive firms can more easily amortize the cost of operating in multiple countries, which reduces their marginal costs, and thus endogenously grow larger.

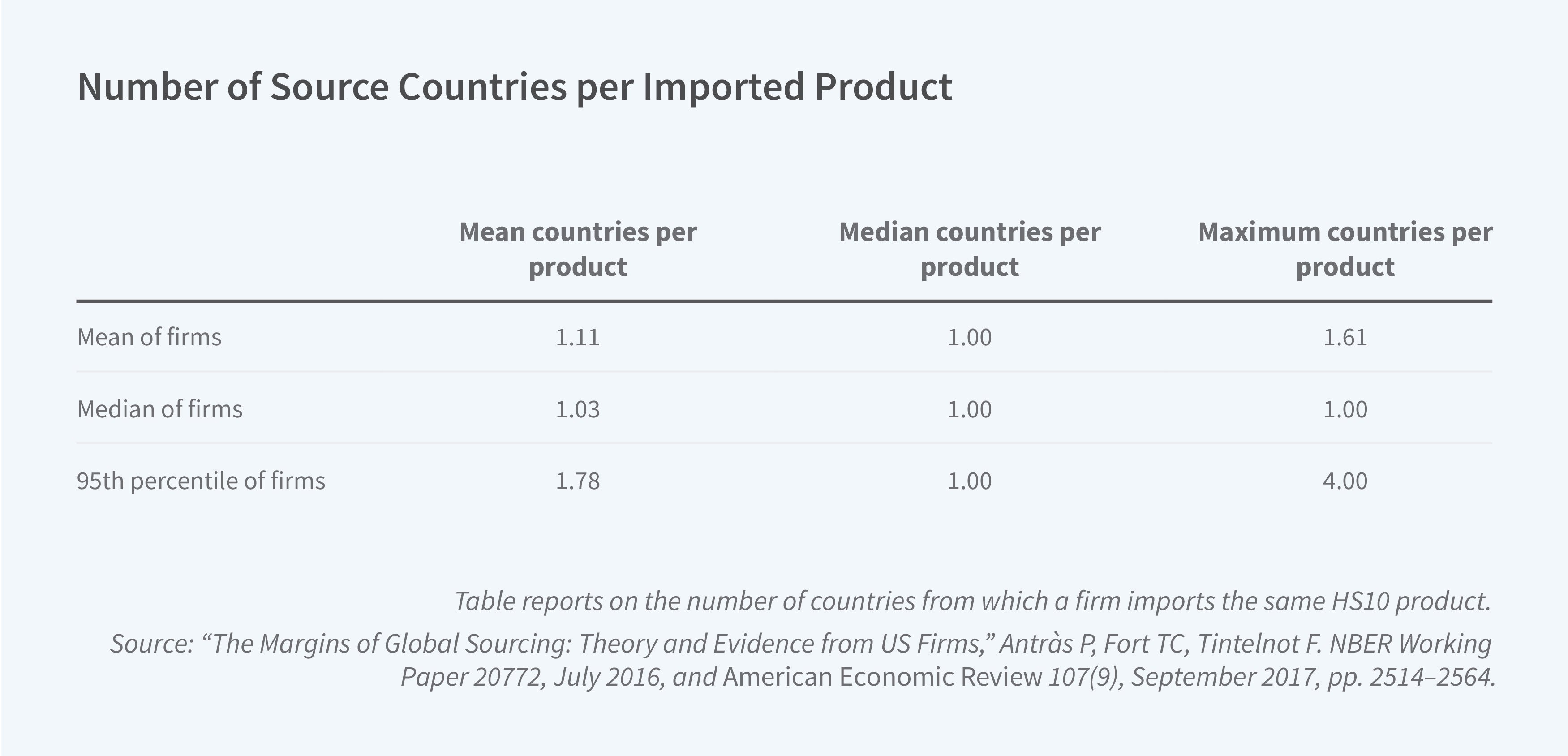

Furthermore, we find that, in 2007, US firms typically sourced each 10-digit product from just one country. The observed patterns, which anticipated the current debates about the lack of diversification and resiliency of global value chains, are again consistent with the existence of sizable fixed costs paid at the firm-country level. Firms did not concentrate their sourcing locations because they were naïve: it is simply costly for them to diversify. Recent changes in policy uncertainty and other supply disruptions have increased the benefits of supply chain diversification. We estimate that fixed costs are large and vary systematically with observable features such as distance, common language, or institutional quality.

Complementary Margins and the Rise of Multinationals

The complementarities we document in firms’ sourcing patterns demonstrate the importance of combining theory and data to analyze how policy will affect global production patterns. Although canonical models of foreign direct investment (FDI) tend to predict that exporting and FDI are substitutes for each other—a firm may serve a particular foreign market either by opening an assembly plant there or by exporting—we consider the possibility that such decisions might instead be complementary. More generally, we develop a framework in which US firm-level decisions to open foreign production plants could interact with their US import and export decisions. To guide our theory, we construct a comprehensive new dataset that links Census production records, transaction-level trade data, and the universe of outward-FDI filings for the year 2007.2

The new data reveal a systematic relationship between the countries from which US firms import, the markets to which they export, and their foreign manufacturing locations. Not only are US multinational enterprises (MNEs) more likely to trade with countries in which they have affiliates, they are also more likely to trade with countries that are proximate to their foreign manufacturing plants. These results point to further complementarities across firms’ global sourcing, production, and marketing decisions. Instead of substituting for domestic production, US multinationals’ US plants are more likely to export to foreign markets that are proximate (in terms of distance and free trade agreements) to their foreign assembly plants.

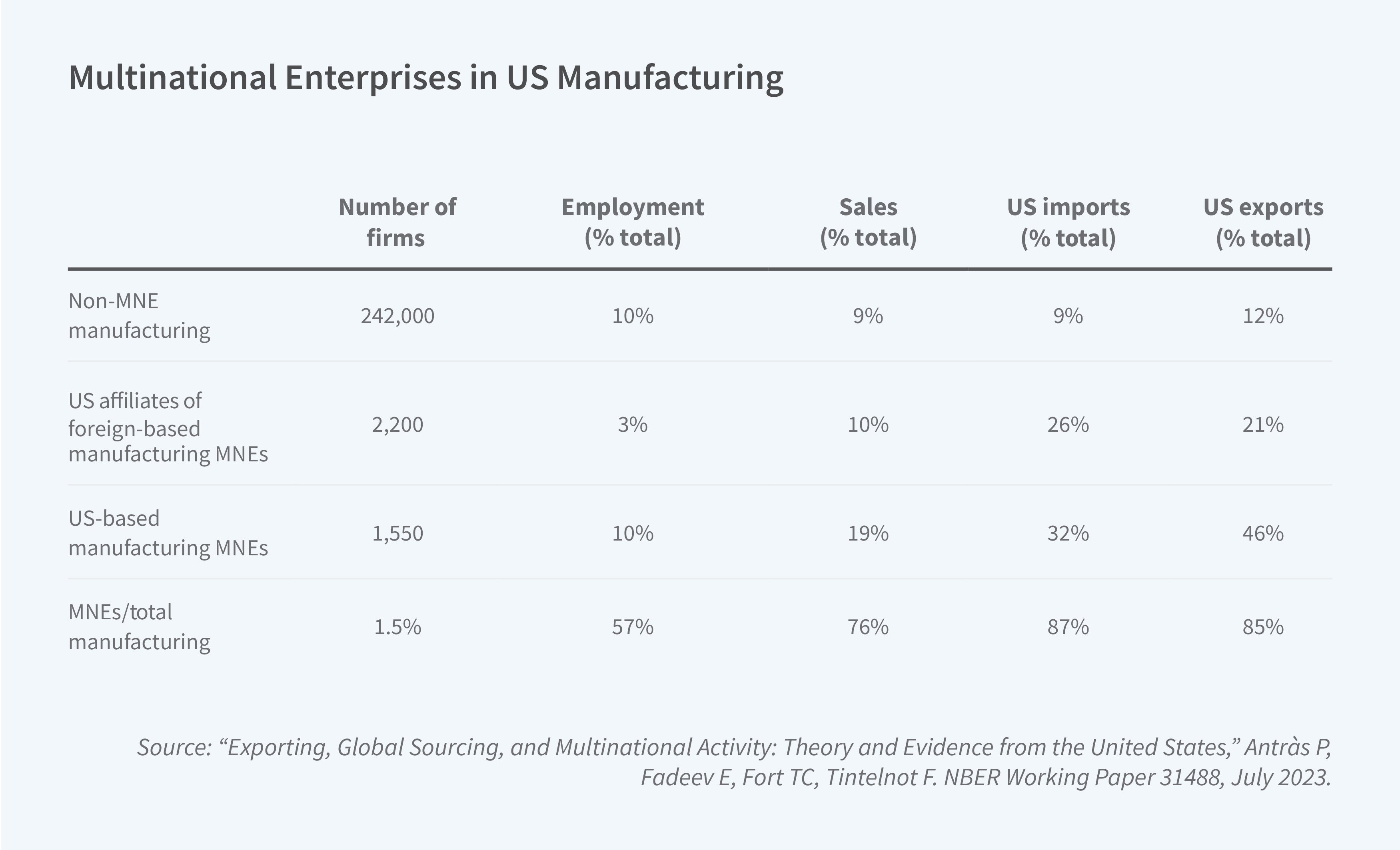

Our merged dataset also highlights the sheer dominance of multinational firms in US trade. There were around 1,550 US MNEs that manufactured in the United States in 2007 and 2,200 US affiliates of foreign-based manufacturing firms. Despite comprising only 1.5 percent of US manufacturers, these MNEs operating in the US accounted for 57 percent of manufacturing employment, 76 percent of sales by manufacturers, 87 percent of manufacturers’ imports, and 85 percent of their exports (see Table 2).

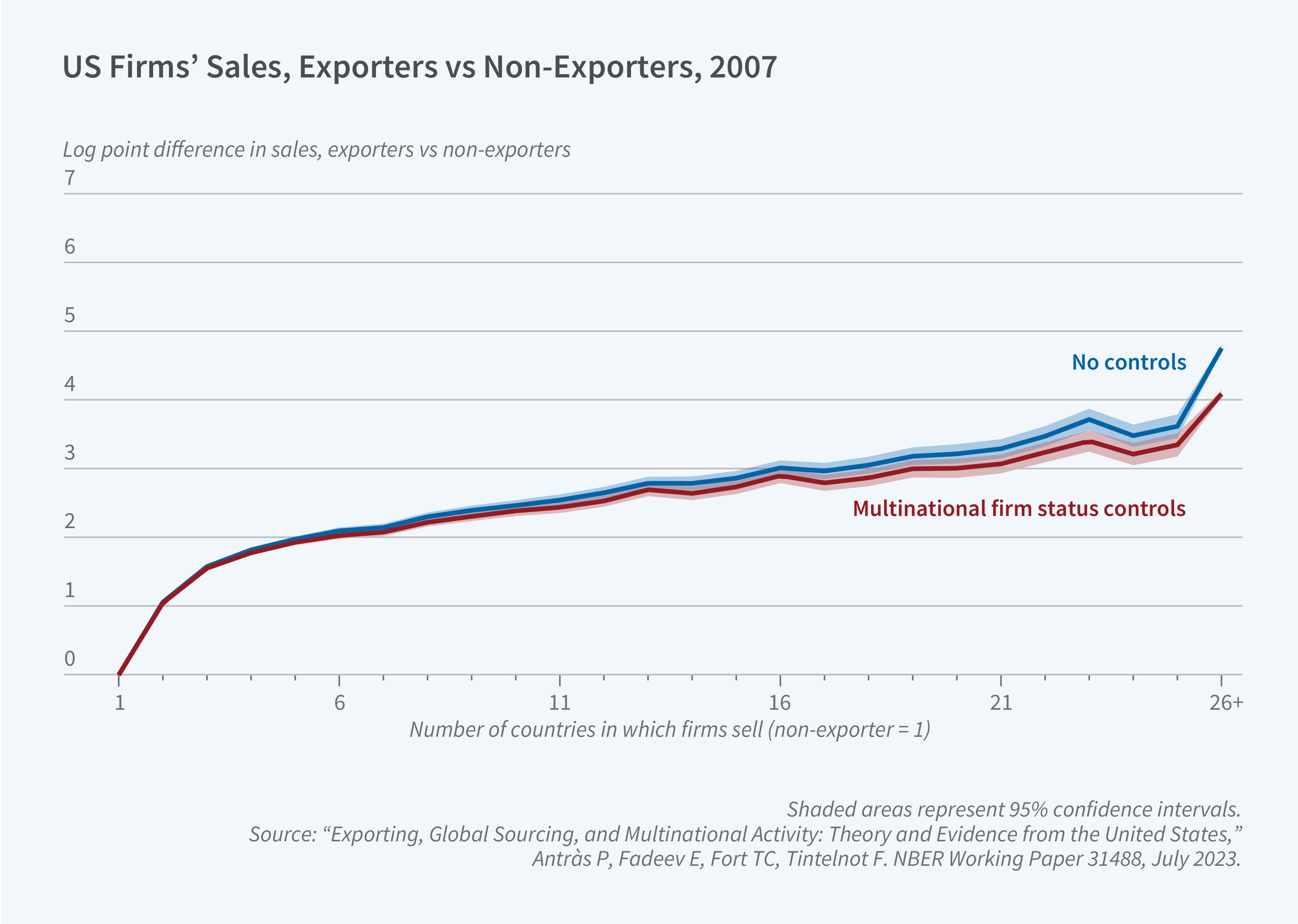

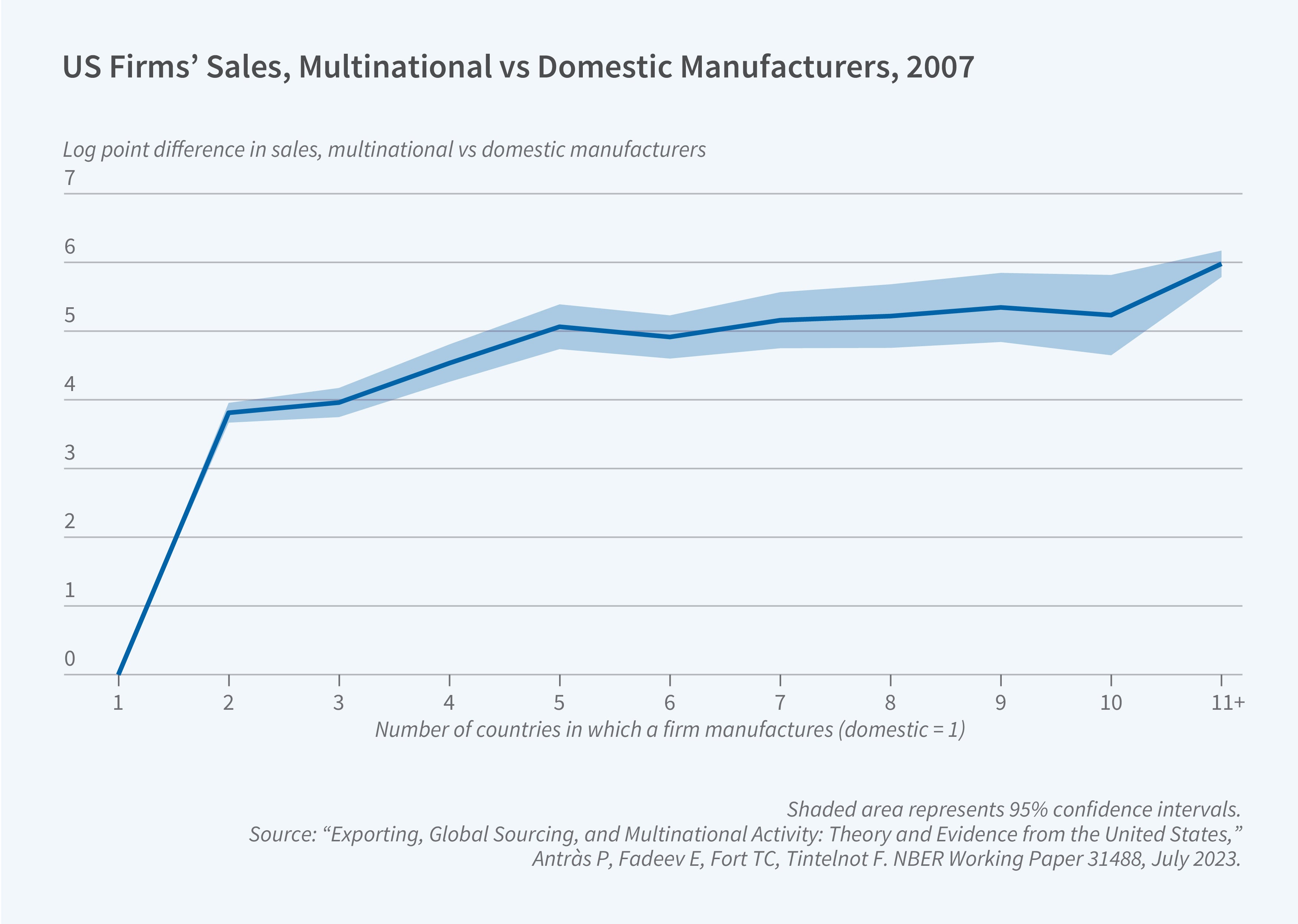

We also show that traders’ well-known size premia relate to their foreign production decisions. Figure 1 shows that the size premium associated with importing from more markets is lower when controlling for a firm’s MNE status. Similarly, firm size increases with the number of markets to which firms export, but less so when controlling for MNE status. Finally, US MNEs’ considerable US size premia increase with the number of countries in which they manufacture. These patterns are suggestive of the quantitative importance of fixed costs of importing, exporting, and foreign assembly, and they also hint at the possibility that plants belonging to MNEs face lower fixed costs to import or export.

We provide a theoretical rationale for why multinational firms are more likely to trade with countries that are proximate to their affiliates, drawing on a new source of firm-level scale economies. In our model, heterogeneous firms choose where to produce, where to sell, and the countries from which to source inputs. To sell in a particular country, a firm must incur a country-specific marketing fixed cost that is shared across all of the firm’s plants. Once the firm pays the cost to enter a destination market, any of its plants may serve that market. Similarly, once the firm pays the fixed cost to source from a given country, all of its plants can access suppliers there. These firm-level fixed costs imply that the marginal benefit of activating a destination or input market rises with the number of plants the firm operates—particularly when that market is proximate, as it faces lower bilateral trade costs.

The model introduces new complementarities between FDI and trade that carry distinct implications for policy. To illustrate these implications, we examine a partial-equilibrium example in which firms in one country (the United States) respond to a trade agreement between two others (North and South). While traditional models predict that such liberalization diverts trade away from the United States, we show that US exports and imports may instead increase due to new FDI. The agreement raises the profitability of investing in North or South, making US firms more likely to open plants there. These new plants, in turn, increase the profitability of activating the same countries as sales destinations or sourcing locations, which in turn weakly raises US import and export levels.

While our framework illustrates a natural complementarity between international trade participation and foreign assembly decisions, it is less clear whether foreign assembly decisions in particular countries are complements or substitutes for assembly decisions in other markets. Traditional export-platform models assume that cost savings at one site “cannibalize” sales from another, but to accommodate contrasting empirical evidence, we have relaxed this restriction.3 A simple extension of our framework yields a clean condition: plants are complements whenever the cross-firm elasticity of demand the MNE faces for its goods is lower than the within-firm elasticity of labor substitution across the MNE’s plants. Shared marketing and sourcing costs again widen the parameter region in which complements prevail. Higher trade barriers faced by a US MNE’s foreign affiliates may decrease its domestic activities if its plants are complements.

A Fresh Look at Tariff Escalation

The economies of scope and scale highlighted in our work are relevant not only for firm-level decisions, but also for governments in their design of trade policies. In recent work, we study how scale economies can explain the fact that tariffs on final consumer goods routinely exceed those on imported inputs both across countries and over time, a pattern dubbed tariff escalation.4 Neoclassical frameworks with constant returns to scale tend to predict that optimal tariffs are uniform across sectors. We show, however, that in general equilibrium, tariff escalation can raise welfare when certain types of production subsidies are infeasible and final-good production features increasing returns to scale. This result is almost automatic when inputs are produced under constant returns to scale. More notably, however, we show that tariff escalation tends to raise welfare even when both inputs and final goods are produced under the same degree of increasing returns. Relatively lower input tariffs are optimal since, despite making inputs cheaper by boosting the size of the sector, an input tariff necessarily pulls labor away from final-good production, which in turn lowers final-good productivity. By contrast, a final-good tariff increases final-good productivity and raises demand for domestic inputs. These results highlight the importance of considering general equilibrium forces when assessing the implications of current tariffs.

In a setting in which US manufacturers face labor shortages, raising tariffs on one industry may have negative consequences for other sectors as they must now pay even higher wages to find workers.

Taking Stock

Calls for reshoring and “friend-shoring” must grapple with a world economy shaped by the interdependencies highlighted in our work. Efforts to pull certain segments of supply chains back home may backfire and instead lead firms to relocate more activity abroad as they seek to maintain stable, reliable, and efficient cost structures. Indeed, the evidence we document for the United States suggests that multinational firms dominate US manufacturing and that their foreign operations are complementary to their domestic activities. In such a case, raising their costs to source from and export to foreign markets will also harm their US activities.

Global value chains will not become less central to policy any time soon. They channel the shocks of pandemics and wars; they condition the diffusion of green technologies; they shape who pays tariffs and who pockets rents. Understanding the microeconomic architecture that underlies those chains is a prerequisite for steering them—toward resilience, toward shared prosperity, or toward whatever goal the next crisis will thrust upon us.

Endnotes

The Margins of Global Sourcing: Theory and Evidence from US Firms,” Antràs P, Fort TC, Tintelnot F. NBER Working Paper 20772, July 2016, and American Economic Review 107(9), September 2017, pp. 2514–2564.

“Exporting, Global Sourcing, and Multinational Activity: Theory and Evidence from the United States,” Antràs P, Fadeev E, Fort TC, Tintelnot F. NBER Working Paper 30450, July 2023.

“Export-Platform FDI: Cannibalization or Complementarity?” Antràs P, Fadeev E, Fort TC, Tintelnot F. NBER Working Paper 32081, January 2024, and AEA Papers and Proceedings 114, May 2024, pp. 130–135.

“Trade Policy and Global Sourcing: An Efficiency Rationale for Tariff Escalation,” Antràs P, Fort TC, Gutiérrez A, Tintelnot F. Journal of Political Economy Macroeconomics 2(1), March 2024, pp. 1–44.