Collusion in Public Procurement

In both developed and developing countries, annual spending on public procurement averages about 12 percent of national GDP. The efficiency of public procurement can have a long-run impact on the growth and productivity of countries. A major challenge in achieving efficiency, however, is the possibility of collusion among suppliers. Collusive agreements increase prices, leading to wasted tax dollars or, in the case of developing countries, wasted foreign aid. These agreements often shield inefficient firms from competition, diverting resource allocation to low-performing sectors of the economy. Furthermore, the transparency requirements inherent to public procurement, such as public databases of past tenders and associated bids, can facilitate the coordination and enforcement of collusive practices.

This summary reviews our recent work on detecting and tackling collusive behavior in procurement auctions.

Detecting Collusion

Historically, antitrust agencies have taken a reactive approach to cartels, initiating investigations only after receiving complaints from clients or competitors or evidence from informed parties. Over the last two decades, some antitrust authorities have begun to take a more proactive approach by using data-driven screens to identify sectors and firms that are more likely to collude. However, such data-driven screens are often suggestive rather than conclusive because the bidding patterns they flag can be rationalized under competition. As a result, as Chassang and Juan Ortner point out, such screens often fail to meet the burden of proof required to launch investigations.1 In a series of studies with collaborators, we develop three families of robust tests that identify bidding patterns used by cartels that are unlikely to be rationalized by any model of competition.

Designated Winners and Designated Losers

Cartels typically designate winners and losers before the auction. The designated winner submits the lowest bid, and the designated losers submit higher cover bids knowing that they will not win. Kawai and Jun Nakabayashi propose a screen for collusion based on this feature.2 They analyze procurement auctions in Japan with secret reserve prices in which rebidding occurs when all (initial) bids fail to meet the secret reserve price. Because designated winners and losers are unlikely to change during the initial auction or the rebid (indeed, the designated winner may have already made arrangements in anticipation of winning), the identity of the lowest bidder will often be persistent under collusion. This should be the case even when the initial bids are very close. Under competition, by contrast, if the initial bids are close, the marginal loser should have close to a 50 percent chance of outbidding the initial low bidder.

Japanese procurement data from 2003 to 2005 show that the initial lowest bidder remains the lowest bidder in the rebid more than 95 percent of the time. More importantly, this probability remains above 95 percent even as the initial auction becomes closer, in the sense that the two lowest bids in the initial auction are almost tied. However, there is a 50 percent probability of the second and third lowest bidders changing regardless of how close the bidders are in the initial auction.

These patterns are consistent with the lowest initial bidder being the designated winner, while the second and third bidders participate in the auction only to create the appearance of competition. The patterns cannot be explained by competitive bidding with heterogeneous bidder costs.

Isolated Winners

A second detection strategy, developed in our work with Nakabayashi and Ortner, seeks to draw inferences from the sample residual demand faced by bidders.3 This demand describes the sample likelihood of winning if the bidder decreases or increases their bid by various amounts. One notable pattern is that winners tend to be isolated: Losing bids close to winning bids are surprisingly rare. As a result, bidders can profitably increase bids without reducing their chances of winning contracts.

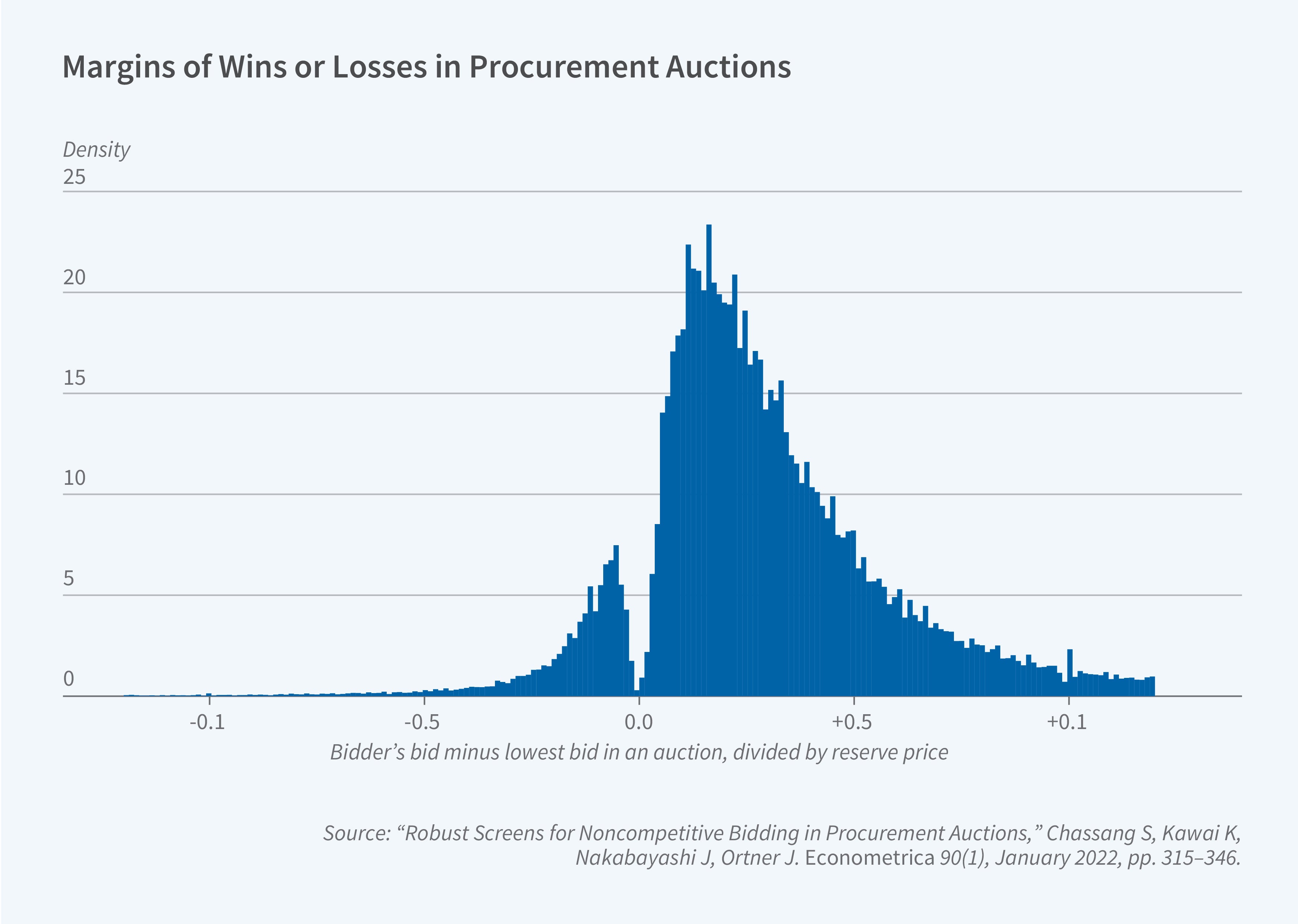

Figure 1 illustrates this point graphically for a subset of procurement auctions. It plots Δ(i,t) for bidder i and auction t; Δi,t denotes this bidder’s margin of defeat or victory. It is negative if bidder i wins auction t and positive otherwise. There are few bids around Δ ≈ 0, which suggests the absence of close losing bids.

The paper systematizes this insight and identifies robust optimality constraints; for example, bidders should not systematically benefit from raising or lowering their bids.4 These constraints should hold under competition even if costs and information follow arbitrary nonstationary processes. The paper then exploits these optimality constraints to compute the share of auctions that need to be noncompetitive in order to rationalize observed bidding patterns.

Incumbency and Rotation Patterns

In related work with Nakabayashi and Ortner, we further study the inferences that can be drawn from bidding patterns when they are associated with other covariates of interest, such as previous auction participation and outcomes.5 Indeed, common allocation schemes used by bidding rings are contingent on past allocation outcomes. Under bid rotation, designated winners rotate, so that a past winner is less likely to be the current winner. Under incumbency-based allocation, incumbent winners are designated winners. Both are forms of market division: bid rotation divides the market across time, while incumbent-based allocation divides the market across contract types or geographic locations.

This has led many antitrust authorities and regulators, including the US Department of Justice and Canada’s Competition Bureau, to flag bid rotation and incumbency advantage as indicators of collusion. It is possible, however, for bid rotation and incumbency patterns to arise under competition as well. Bid rotation will naturally arise under competition if large amounts of recently awarded work increase marginal costs. Incumbency advantage can arise under competition if some firms specialize in certain types of projects or if geographic proximity to customers lowers costs. Incumbency advantage can also arise with learning by doing. Hence, it is not obvious that bid rotation and incumbency patterns can be used as markers of collusion. Developing tests that can help distinguish between collusive and competitive explanations for rotation or incumbency patterns has been a long-standing challenge.

We propose a test of noncompetitive behavior targeting rotation and incumbency patterns using an approach related to regression discontinuity.6 The key idea is to compare the characteristics of winners and losers conditional on the lowest and second-lowest bids being close. Indeed, we establish that under competition, conditional on being a close winner or loser, a bidder should win or lose with equal probability. As a result, close winners and close losers should be statistically similar.

Consider two firms regularly bidding on different auctions whose roles as incumbents or entrants may vary depending on the auction. If the auction is competitive, incumbents have a lower cost of procurement: Incumbents tend to win and, conversely, winners tend to be incumbents. However, the likelihood of being an incumbent is continuous in the bid difference. Conversely, if the likelihood of being an incumbent is not continuous in the bid difference at 0, as in Figure 1, then bidding is inconsistent with competitive behavior.

Applications Across Countries

Ohio School Milk Auctions

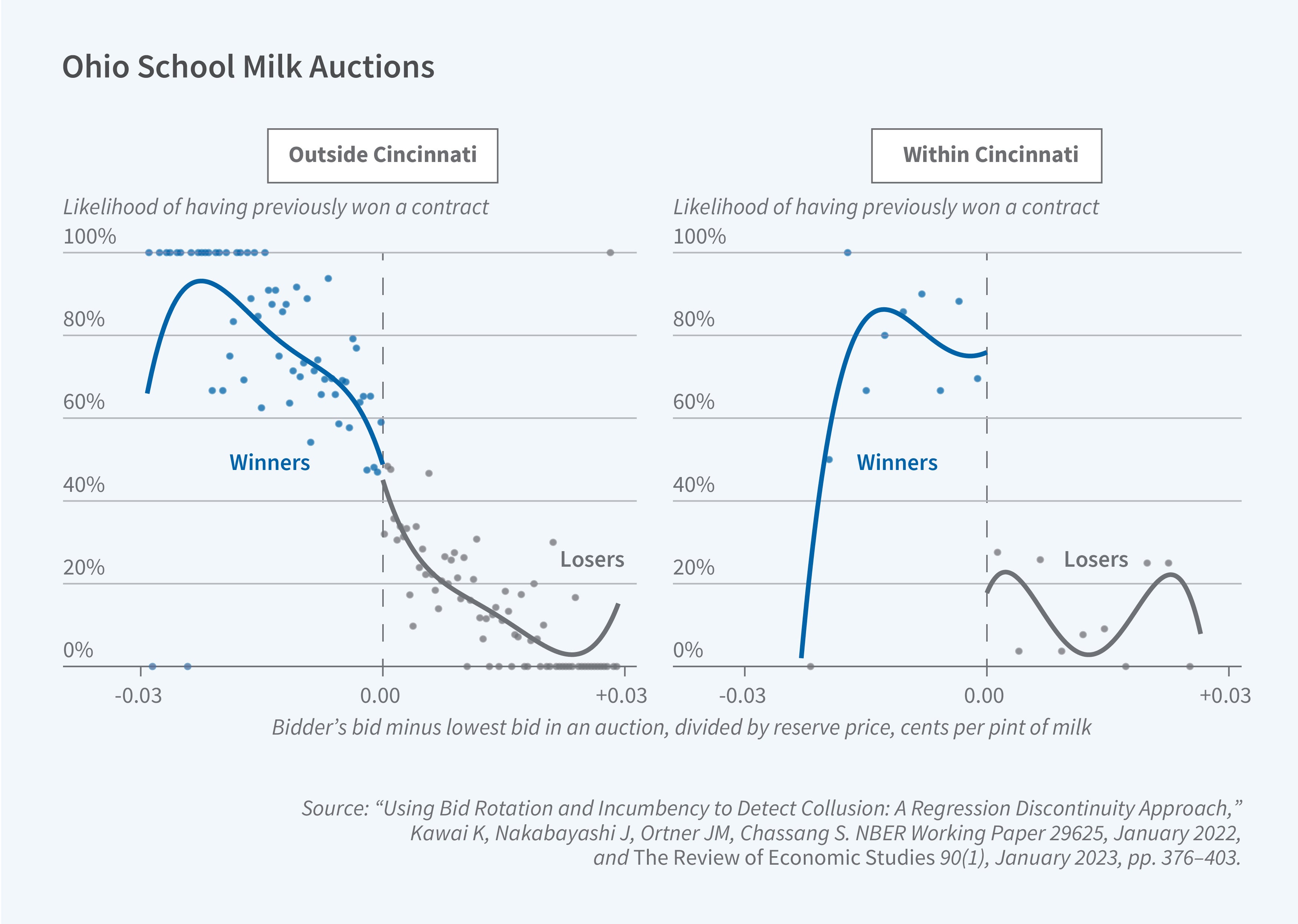

Our first application of the screen is to school milk auctions in Ohio studied by Robert Porter and J. Douglas Zona.7 Before the start of every school year, school districts hold auctions to determine the provider of school milk for the following year. During most of the 1980s, dairies around Cincinnati, Ohio, colluded on auctions conducted by nearby school districts. Specifically, the colluding bidders agreed to designate the incumbent as the winner so that each bidder could keep serving the same school districts year after year. The incumbent placed the lowest bid and the nonincumbents placed higher bids in order to make sure that the incumbent won the auction as intended.

Figure 2 is a bin scatterplot of incumbency status and the margin of victory or defeat, Δi,t, for the set of colluding auctions around Cincinnati (left panel) and those outside of Cincinnati (right panel). The bid difference Δi,t is in units of cents per pint of milk. The circles in the figure correspond to bin averages and the curves in the figure correspond to estimates of the mean for winners (Δi,t < 0) and losers (Δi,t > 0). The left panel shows that winners are much more likely to be incumbents and that this is true even for marginal winners. In the right panel, winners are much more likely to be incumbents, but marginal winners and losers are equally likely to be incumbents. The fact that our screen can reject the null of competition for the Cincinnati auctions and that it correctly fails to reject the null for other auctions suggests that the test is useful for detecting collusion.

Japanese Procurement Auctions for Public Works

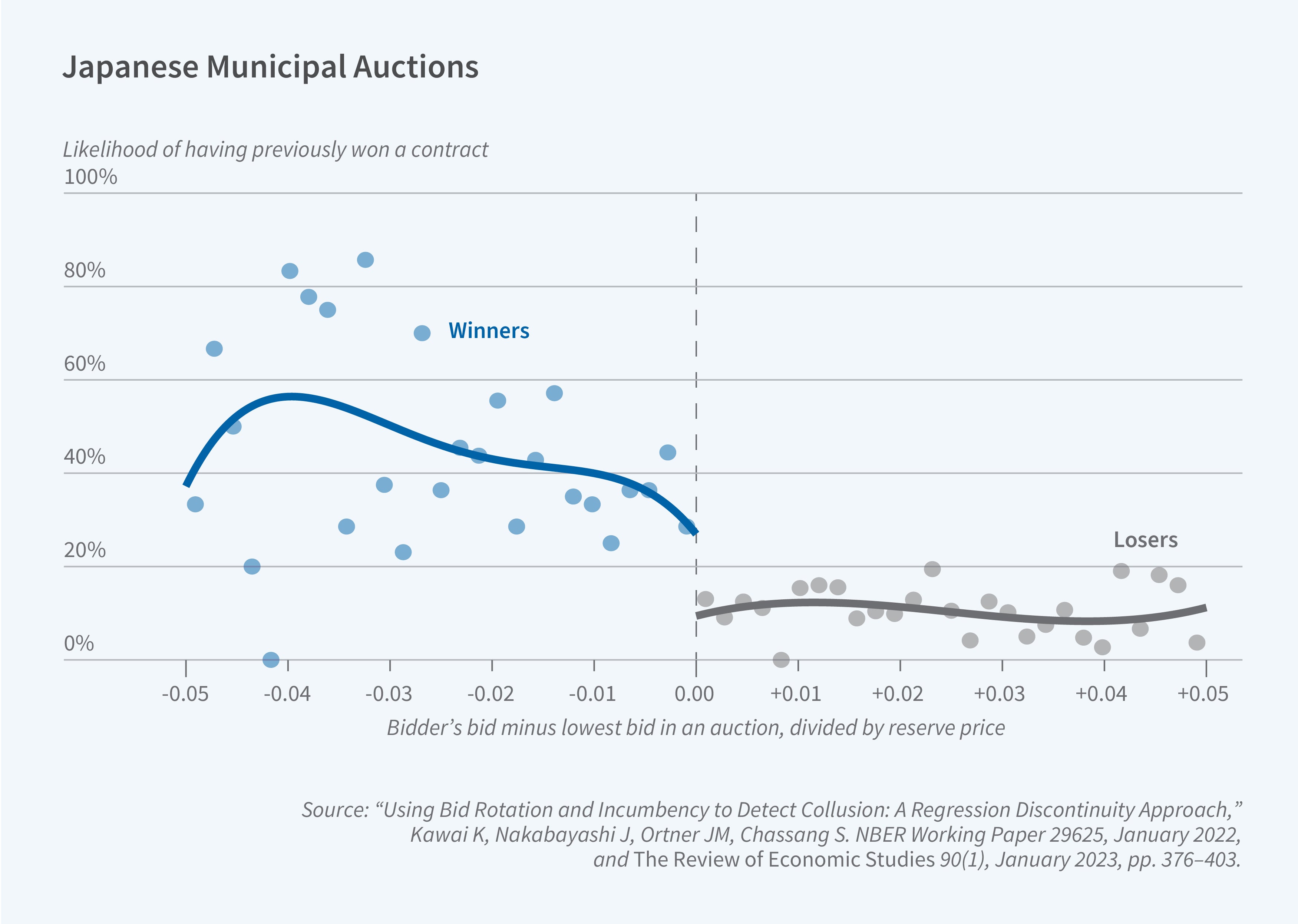

We have also applied our test to Japanese procurement auctions for public works contracts. In this setting, it is not always straightforward to identify an incumbent since many public works projects are unique. Hence, we first focus on the set of recurring auctions, which are typically auctions for repair and maintenance contracts.

Figure 3 plots the bid difference Δi,t and incumbency for recurring auctions. We find that a much higher proportion of marginal winners tend to be incumbents than marginal losers, which suggests that there is collusion in these auctions.

The set of recurring auctions is less than 5 percent of our sample. When incumbency is difficult to define clearly, bidding rings are likely to resort to other allocation rules, such as rotation.

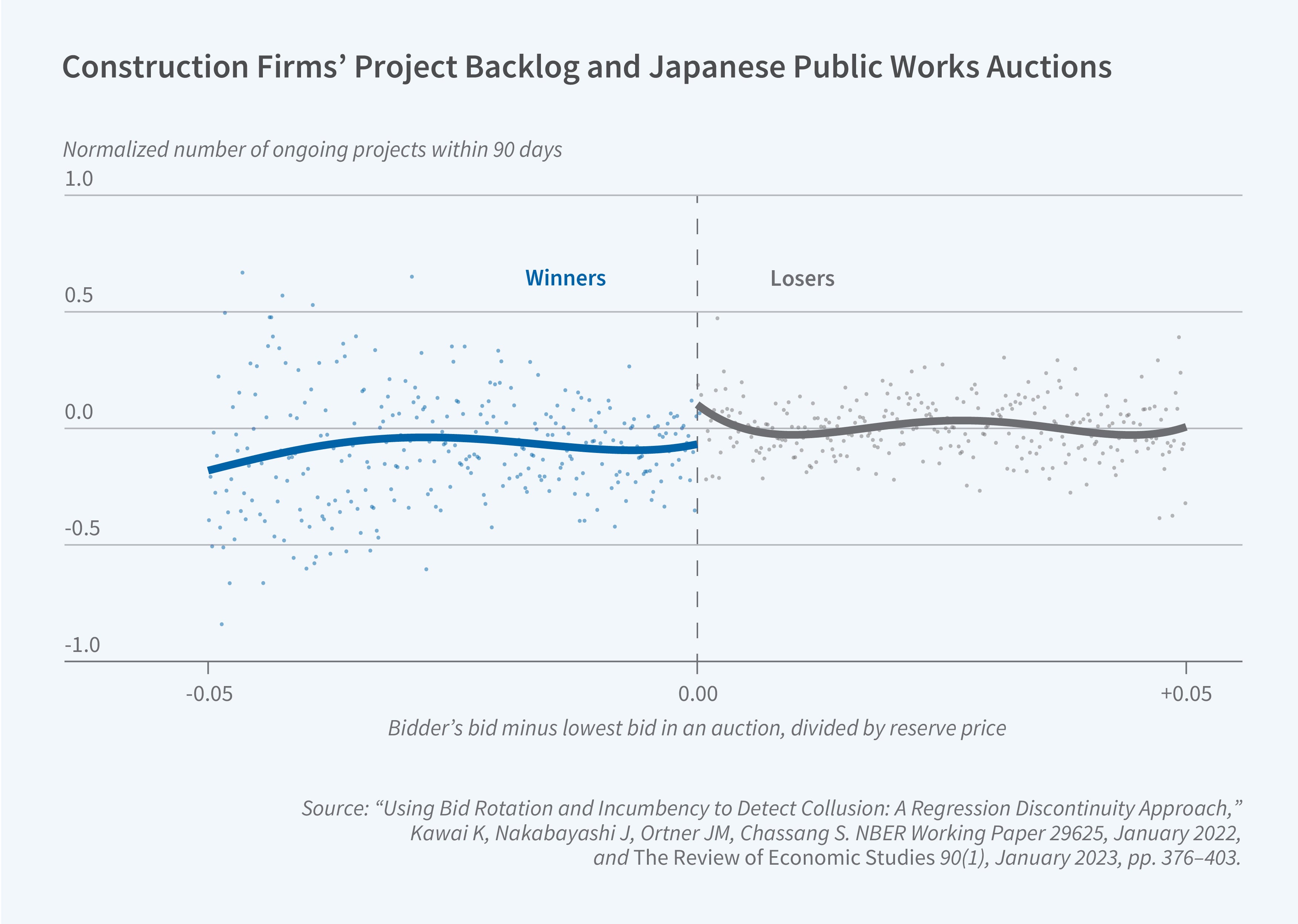

To detect cartels among a broader set of public works auctions, we consider a test that screens for bid rotation. A defining feature of bid rotation is that the winner has less recently awarded work than the losers because bidders take turns winning auctions. We consider a measure of recently awarded work, B90i,t, which is the number of projects firm i has won in the 90 days preceding auction t. We plot backlog Bi,t for all firms i and all auctions t in Figure 4. Because the sample contains very large auctions and relatively small auctions, we scale Δi,t by the reserve price so that Δi,t is in units of percentages of the reserve price. Similarly, we normalize the backlog measures by the firm-specific mean and the standard error. If firm i has a larger backlog at auction t relative to its historical average, the backlog measures will be positive, and vice versa.

This test considers how incumbency or backlog can be used as outcome variables in a regression discontinuity framework to detect collusion. Depending on the nature of the cartel’s allocation rule, other outcome variables can be used to detect collusion. For example, in offshore oil and gas tract auctions, some believe that bidders give priority to those who already own a neighboring tract. In this instance, one could screen for collusion by making the outcome variable a neighbor. In other contexts, bidders may allocate auctions depending on how close they are to the construction site, so this distance could be the outcome variable.

Tackling Collusion

What are the next steps after likely collusion is detected? While data-driven screens can sometimes be used to justify further investigation through official legal channels, suspect bidding behavior on its own often does not provide grounds for legal action. The recent evolution in US case law, in particular Bell Atlantic v. Twombly, has changed the burden of proof needed to initiate discovery.8 Moreover, the law penalizes conspiracies to fix prices rather than tacit collusion. As a result, the US Department of Justice offers leniency to parties that come forward; this is the leading source of legally actionable information on cartels.9

There are alternative paths available to auctioneers who have become aware that bidders have organized. Auctioneers can alter the auction design to introduce frictions known to make cooperation between cartel members more difficult.

Making Punishment Difficult

Cartels must maintain discipline. Cartel members and potential entrants tempted to undercut a designated winner are prevented from doing so by threat of retaliation via price wars. Some of our work investigates the impact on winning bids of minimum price guarantees, which limit the extent of competition, and the scope for punishment via price wars.10 In municipal procurement data from Japan, the introduction of minimum price guarantees leads to lower bids and greater entry in auctions that are likely cartelized. This is consistent with the interpretation that minimum price guarantees weaken the cartel’s ability to maintain discipline. In this setting, a prudent choice for minimum prices is a lower quantile of the range of winning bids observed. The guarantee should be low enough that it does not mechanically increase prices, yet high enough that it effectively constrains the cartel.

Injecting Imperfect Monitoring

Transparency requirements associated with good governance principles likely facilitate collusion in public procurement auctions. Maintaining collusion becomes difficult when losing bids are hidden.11 One of our recent studies analyzes the introduction of scores in the tendering process used by the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.12 We argue that in competitive environments, switching from first-price auctions to scoring auctions should increase prices. However, in the setting we study, the introduction of scoring led to a reduction in prices. Upon further investigation of the data, we find that scoring weakened overall cartel discipline and was particularly effective because it created an imperfect monitoring problem across cartel members. Because scores are noisy subjective evaluations of proposals, it is difficult for bidders to reliably ensure that an intended winner will in fact win.

Endnotes

“Regulation Collusion,” Chassang S, Ortner J. Annual Review of Economics 15, March 2023, pp. 177–204.

“Detecting Large-Scale Collusion in Procurement Auctions,” Kawai K, Nakabayashi J. Journal of Political Economy 130(5), May 2022, pp. 1364–1411.

“Robust Screens for Noncompetitive Bidding in Procurement Auctions,” Chassang S, Kawai K, Nakabayashi J, Ortner J. Econometrica 90(1), January 2022, pp. 315–346.

“Using Bid Rotation and Incumbency to Detect Collusion: A Regression Discontinuity Approach,” Kawai K, Nakabayashi J, Ortner JM, Chassang S. NBER Working Paper 29625, January 2022, and The Review of Economic Studies 90(1), January 2023, pp. 376–403.

“Ohio School Milk Markets: An Analysis of Bidding,” Porter RH, Zona D. NBER Working Paper 6037, May 1997, and RAND Journal of Economics 30(2), Summer 1999, pp. 263–288.

“Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly,” Justia, 2007, Docket Number 05-1126.

“Regulation Collusion,” Chassang S, Ortner J. Annual Review of Economics 15, March 2023, pp. 177–204.

“Collusion in Auctions with Constrained Bids: Theory and Evidence from Public Procurement,” Chassang S, Ortner J. Journal of Political Economy 127(5), October 2019, pp. 2269–2300.

“The Value of Privacy in Cartels: An Analysis of the Inner Workings of a Bidding Ring,” Kawai K, Nakabayashi J, Ortner JM. NBER Working Paper 28539, March 2021, and forthcoming in The Review of Economic Studies.

“Scoring and Cartel Discipline in Procurement Auctions,” Nakabayashi J, Ortner JM, Chassang S, Kawai K. NBER Working Paper 33668, April 2025.