International Migration, Remittances, and Economic Development

The international development community — and development economists in particular — are constantly on the lookout for effective anti-poverty interventions for developing societies. The most dramatic income gains arise when people move from a developing country to a developed country for work. Migrants can experience fivefold wage gains, an improvement that dwarfs other interventions.1,2

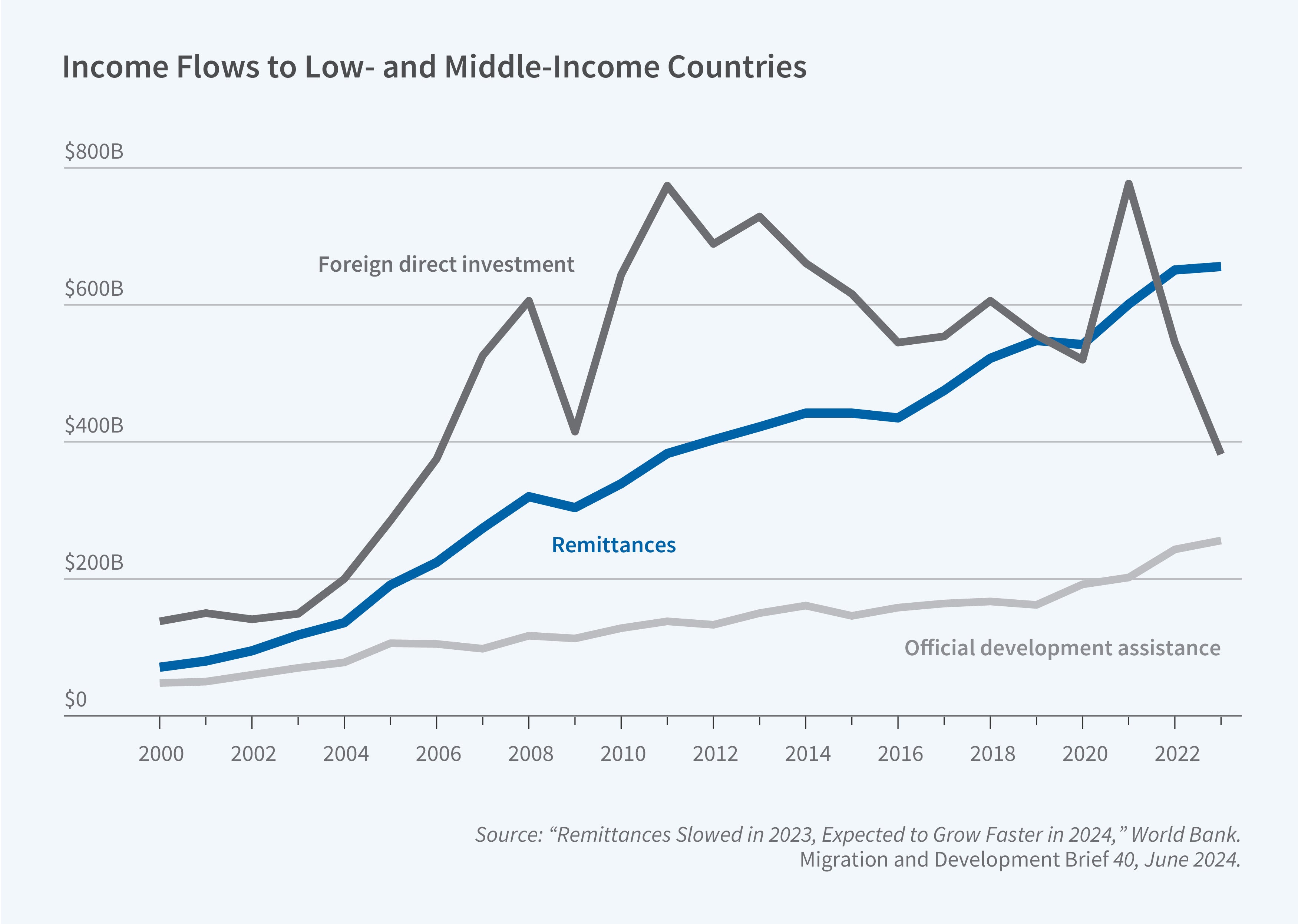

Do migrants’ origin communities gain from international migration as well? The aggregate numbers of migrants and the funds they send home suggest the potential for large impacts. In 2020, 281 million people lived outside their country of birth, up from 173 million in 2000.3 International migrants typically remit large portions of their incomes to beneficiaries in their origin areas. Migrant remittances rose from $71 billion in 2000 to $656 billion in 2023, making them one of the largest types of international financial flows to developing countries.4 Remittances are typically more than twice the value of official development assistance (foreign aid), and often approach or surpass the value of FDI flows (Figure 1).

In my research, I seek to understand how international migration affects development in migrants’ origin countries. To do so, I take advantage of natural experiments and use randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of approaches aimed at increasing the development impact of migrant remittances and improving the outcomes of international migrants.

Economic Impacts of Migration on Origin Countries

What effects do migrant earnings have on migrants’ origin households? I exploit a natural experiment to examine the causal impact of changes in the economic circumstances of migrants on remittances and other outcomes in migrant origin households.5 Many households in the Philippines have one or more members working overseas at any one time. These overseas Filipinos work in dozens of foreign countries and experienced sudden changes in exchange rates due to the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The exchange rate shocks were unexpected and varied in magnitude across overseas Filipinos’ locations: in the year following the crisis, the US dollar and currencies in the main Middle Eastern destinations of Filipino workers appreciated by 50 percent against the Philippine peso. By contrast, the currencies of Taiwan, Singapore, and Japan rose by only 26 percent, 29 percent, and 32 percent, while those of Malaysia and Korea fell slightly against the peso. I examine the impacts of these exchange rate shocks on migrants’ origin households using panel household survey data.

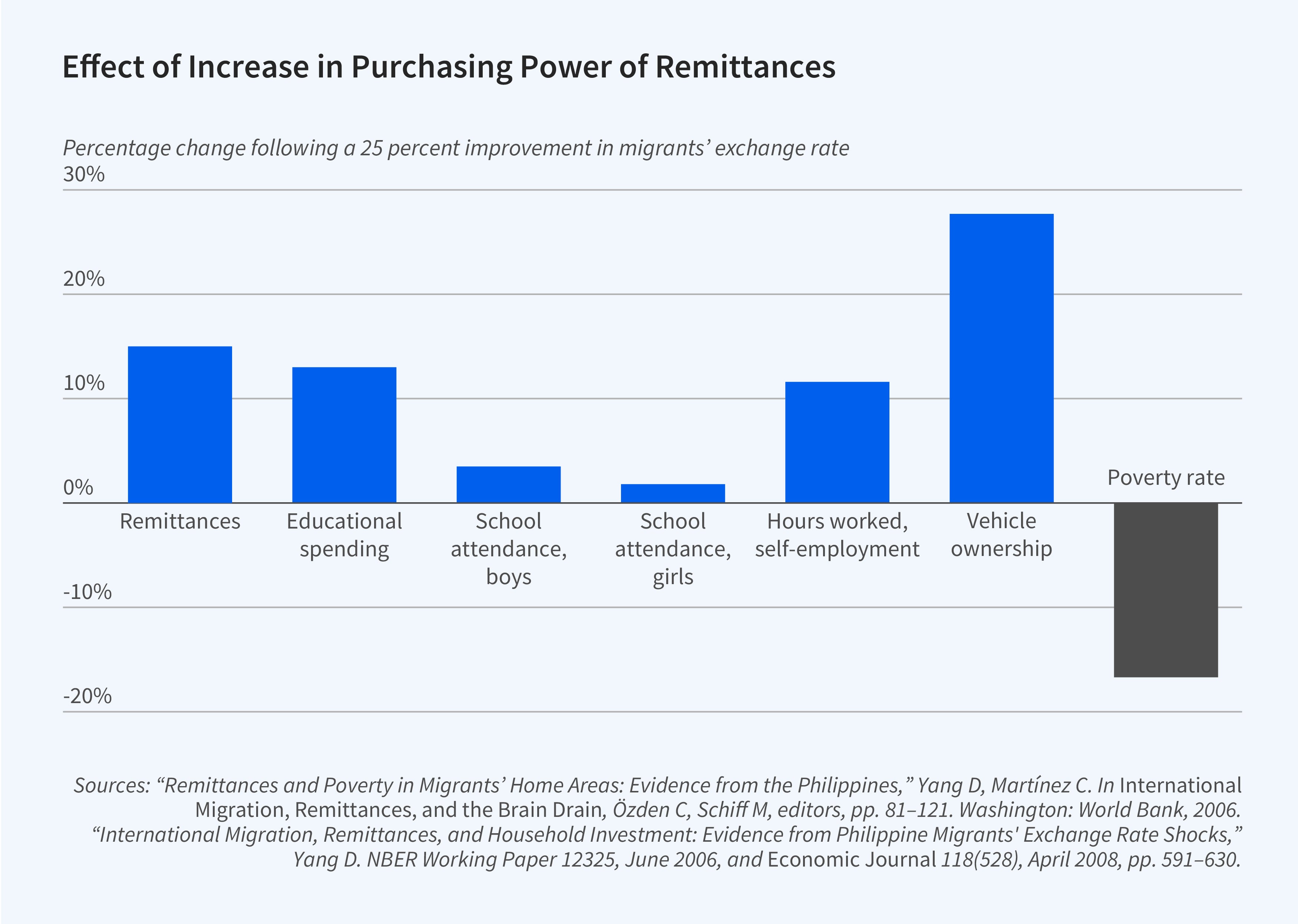

When migrants experience positive exchange rate shocks, there are substantial positive impacts on their origin households. Figure 2 displays the impact of a 25 percent improvement in the exchange rate facing migrants, well within the range of actual shocks. It leads to a 15 percent increase in remittances over the subsequent 15 months. These additional resources are channeled primarily into investments: educational spending rises by 13 percent, school attendance increases for both boys (3.5 percent) and girls (1.8 percent), and households increase their entrepreneurial activity, with hours worked in self-employment rising by 11.6 percent. There is a substantial increase in the number of vehicles owned, which are probably partly used for business (households become more likely to have transportation businesses). Notably, overall labor supply stays stable. Claudia Martínez and I show that a shock of this magnitude leads to a 16.7 percent fall in the poverty rate.6 These findings suggest that migrants’ earnings have substantial positive effects on the long-run economic prospects of their origin households.

In a related paper, I show how Filipino migrant workers’ decisions to return from overseas and to invest in household enterprises are intertwined. A substantial fraction appear to be “target earners” who wait until they have saved a threshold amount and then return home and invest.7

While migrant resources have positive impacts on households, what are the effects on the local economy overall? Gaurav Khanna, Emir Murathanoglu, Caroline Theoharides, and I address this question, focusing on impacts across 74 Philippine provinces. Our empirical approach also involves the 1997 Asian financial crisis exchange rate shocks, but this time exploits the fact that provinces vary at baseline (prior to the crisis) in the importance of overseas migrant income as a share of provincial income, as well as in the international destinations where migrants work.8 Provinces thus faced heterogeneous shocks to the value of overseas migrants’ income on a provincial per capita basis. We find that positive shocks to migrant income have substantial and long-lasting economic impacts in Philippine provinces. Increases in migrant income lead to investments in education and small enterprises in origin provinces. Investments in education play a large role in raising the incomes of future overseas migrants from the province, as well as income from domestic (nonmigrant) sources back home. Initial positive migrant income shocks are magnified over time: there is a virtuous cycle in which initial education investments lead future migrants to be better educated and work in higher-skilled jobs. In the long run, increases in domestic income are larger than migrant income gains. An initial 1 standard deviation positive shock to migrant income increases global (migrant plus domestic) income per capita by 0.2 standard deviations, or 2,272 Philippine pesos, over the long run.

Income from international migration not only improves a range of outcomes in origin areas, it also helps them cope with negative shocks. HwaJung Choi and I study how migrants help attenuate the effects of adverse shocks associated with rainfall.9 Among households in the Philippines with overseas migrant members, rainfall-driven income shocks are associated with changes in remittances in the opposite direction: remittances fall when income rises, and vice versa. In such households, roughly 60 percent of exogenous declines in income are replaced by remittance inflows from overseas. In another paper, I examine the impact of hurricanes on international financial flows using country-level panel data.10 For the poorest developing countries, hurricane damage leads to large inflows of migrant remittances amounting to 20 percent of experienced damages. The remittance response is roughly one-quarter as large as the response of foreign aid. Finally, Parag Mahajan and I show that migration itself can be a mechanism for coping with negative shocks.11 We assemble country-level panel data on hurricanes around the world and show that they cause migration to the US. The migration response is larger in origin countries with larger stocks of migrants already in the US, which illustrates how migrant networks facilitate international migration. A key channel is prior migrants sponsoring new migrants for green cards (permanent residency).

Enhancing Development Impacts of Remittances

To investigate ways to increase the beneficial impacts of remittances, I have conducted RCTs that enhance migrants’ ability to control or monitor how remittances are used in the origin country. Migrants often are seen as having strong preferences to save or invest remittances for the future; giving them more control over the use of remittances may have positive effects on development outcomes.

Nava Ashraf, Diego Aycinena, Martínez, and I conducted an RCT among US-based migrants from El Salvador.12 We randomized offers of financial tools that improve the ability of migrants to ensure that remittances are deposited and accumulated in savings accounts in their home country. The savings may be for future use by the recipient household or the migrant. Some migrants may send their funds to be saved in El Salvador because they perceive savings held in the US to be relatively insecure.

Migrants in the study were randomly assigned to a control group or to one of three treatment conditions that provided them varying levels of monitoring and control over their savings in El Salvador. Comparisons across the treatment conditions revealed the causal impacts of offering varying degrees of control on savings account take-up, savings balances, and remittances.

The results support a desire for monitoring and control over remittance uses—in particular, over the extent to which remittances are saved in formal savings accounts. Across the experimental conditions in our sample, migrants were much more likely to open savings accounts and accumulate more savings in El Salvador if they were assigned to the treatment condition offering the greatest degree of monitoring and control.

In other studies, we have found that migrants also desire control over the use of remittances to finance education. Kate Ambler, Aycinena, and I implemented an RCT offering Salvadoran migrants the ability to directly fund educational expenses for students of their choice in El Salvador.13 Additional treatments provided matching funds for these educational remittances. We found that demand for control in this context is elastic with respect to the match rate: there was no demand for unmatched educational remittances, but positive demand when matched. The offer of the match caused increased educational expenditures, higher private school attendance, and lower labor supply of youths in Salvadoran households connected to migrant study participants. We found substantial “crowd in”: for each $1 received by beneficiaries, educational expenditures increased by $3.72.

In another study, Giuseppe De Arcangelis, Majlinda Joxhe, David McKenzie, Erwin Tiongson, and I investigate the impact of offering Filipino migrants in Italy control over the use of remittances for education in the Philippines.14 We find evidence in a field experiment that people share more with home-country family members when they can channel those funds towards education or signal that the funds are intended for education.

Helping Migrant Workers

International migrant workers often face significant challenges in their destination countries. I have studied interventions that could help improve their outcomes. Toman Barsbai, Vojtech Bartos, Victoria Licuanan, Andreas Steinmayr, Tiongson, and I ran an RCT of an intervention aimed at reducing mistreatment of Filipino women employed as domestic workers in Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia.15 The intervention — encouraging workers to show employers a family photo while providing a small gift when starting employment — reduced worker mistreatment, improved satisfaction with employers, and increased job retention. The mechanism appears to be a reduction in employers’ perceived social distance from employees.

We have also found that information provision to migrants can have complex effects on their social networks. Barsbai, Licuanan, Steinmayr, Tiongson, and I conducted an RCT among new Filipino immigrants to the US that improved information about settling in the US.16 The treatment led immigrants to acquire fewer new social network connections. Treated immigrants make fewer new friends and acquaintances and are less likely to receive support from organizations of fellow immigrants. This suggests that information and social network links can be substitutes: better-informed immigrants invest less in expanding their social networks upon arrival.

In Conclusion

International migration generates substantial economic benefits not only for migrants themselves but also for their origin communities. It can be a powerful tool for economic development, enabling investments in education and entrepreneurship while providing insurance against economic shocks. Our research has shown that these positive impacts can be further enhanced through interventions that give migrants more control over remittance use and that help improve their working conditions abroad. The demonstrated success of various interventions suggests promising avenues for expanding the economic development benefits of international migration in the future.

Endnotes

“The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers,” Clemens MA, Montenegro CE, Pritchett L. The Review of Economics and Statistics 101(2), May 2019, pp. 201–213.

“How Important Is Selection? Experimental vs. Non-Experimental Measures of the Income Gains from Migration,” McKenzie D, Stillman S, Gibson J. Journal of the European Economic Association 8(4), June 2010, pp. 913–945.

“Long-Term Impacts of International Migration: Evidence from a Lottery,” Gibson J, McKenzie D, Rohorua H, Stillman S. The World Bank Economic Review 32(1), February 2018, pp. 127–147.

“Economics of International Wage Differentials and Migration,” Pritchett L, Hani F. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance, July 2020.

“International Migrant Stock 2020,” United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020), December 2020.

“Remittances Slowed in 2023, Expected to Grow Faster in 2024,” World Bank Group press release, June 26, 2024.

“International Migration, Remittances, and Household Investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks,” Yang D. NBER Working Paper 12325, June 2006, and Economic Journal 118(528), April 2008, pp. 591–630.

“Remittances and Poverty in Migrants’ Home Areas: Evidence from the Philippines,” Yang D, Martínez CA. In International Migration, Remittances, and the Brain Drain, Ozden C, Schiff M, editors, pp. 81–121. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2005.

“Why Do Migrants Return to Poor Countries? Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Responses to Exchange Rate Shocks,” Yang D. NBER Working Paper 12396, July 2006, and Review of Economics and Statistics 88(4), November 2006, pp. 715–735.

“Abundance from Abroad: Migrant Income and Long-Run Economic Development,” Khanna G, Murathanoglu E, Theoharides CB, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 29862, October 2022.

“Are Remittances Insurance? Evidence from Rainfall Shocks in the Philippines,” Yang D, Choi H. World Bank Economic Review 21(2), May 2007, pp. 219–248.

“Coping with Disaster: The Impact of Hurricanes on International Financial Flows, 1970–2002,” Yang D. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 8(1), 2008, Article 13.

“Taken by Storm: Hurricanes, Migrant Networks, and US Immigration,” Mahajan P, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 23756, August 2017, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(2), April 2020, pp. 250–277.

“Savings in Transnational Households: A Field Experiment among Migrants from El Salvador,” Ashraf N, Aycinena D, Martínez C, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 20024, March 2014, and Review of Economics and Statistics 9(2), May 2015, pp. 332–351.

“Channeling Remittances to Education: A Field Experiment Among Migrants from El Salvador,” Ambler K, Aycinena D, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 20262, June 2014, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(2), April 2015, pp. 207–232.

“Directing Remittances to Education with Soft and Hard Commitments: Evidence from a Lab-in-the-Field Experiment and New Product Take-Up Among Filipino Migrants in Rome,” De Arcangelis G, Joxhe M, McKenzie D, Tiongson E, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 20839, January 2015, and Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 111, March 2015, pp. 197–208.

“Picture This: Social Distance and the Mistreatment of Migrant Workers,” Barsbai T, Bartos V, Licuanan V, Steinmayr A, Tiongson E, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 30804, December 2022, and forthcoming in the Journal of Political Economy Microeconomics.

“Information and the Acquisition of Social Network Connections,” Barsbai T, Licuanan V, Steinmayr A, Tiongson E, Yang D. NBER Working Paper 27346, June 2020, and published as “Information and Immigrant Settlement,” Journal of Development Economics 170, September 2024.