The Taxation of Business Income in the Global Economy

It is a great pleasure to give the Martin Feldstein Lecture at the NBER Summer Institute. Marty was my dissertation adviser and a coauthor, and I learned a lot from him over the years. Indeed, I want to begin with a couple of Marty’s contributions to the topic of my lecture, not simply to remind us how versatile Marty was in his research, but also because the points he made in these papers inform my discussion.

The first of these contributions is a paper that Marty wrote with David Hartman in the late 1970s that derived optimal tax rates for the domestic and foreign source income of multinational companies.1 Key implicit assumptions in the paper were that companies’ residence, and where they earn their income, are well determined. Both assumptions were perhaps quite sensible in the 1970s, but they clearly are not today.

Let me also call to your attention Marty’s paper with Paul Krugman in an NBER conference volume.2 The paper has the following quotation, expressing its aim: “The point of this analysis is more modest; we want to show that the common belief that a VAT [value-added tax] is a kind of disguised protectionist policy is based on a misunderstanding.” This was an important clarification to make then, given the extent of misunderstanding. Unfortunately, it still is needed today, when policymakers debate the merits not only of value-added taxes, but of other consumption-based or destination-based taxes. This was evident during the US tax reform debate a few years ago.

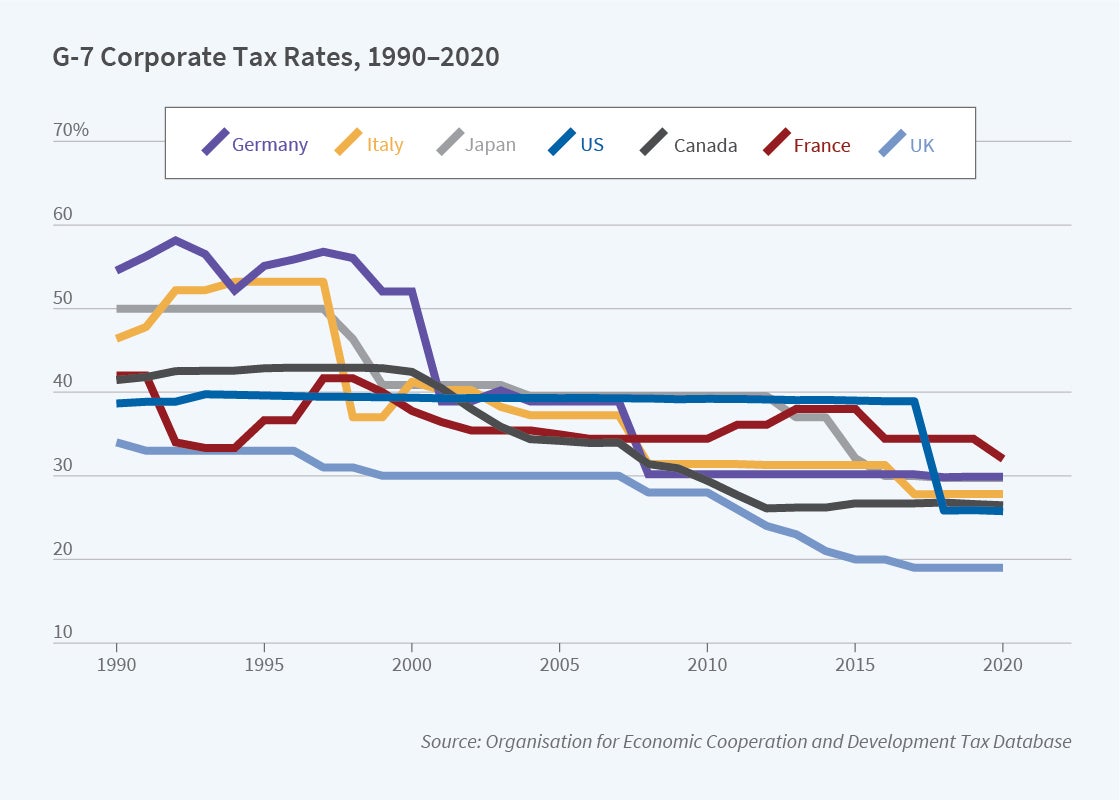

To continue, let me start with a figure common to discussions of international taxation today, the G7 corporate tax rates going back a few decades. One would get a similar picture looking at other groups of developed countries.

It is evident that corporate tax rates have been declining throughout this period, starting from a much higher range in the early to mid-1990s than now. It’s also worth pointing out that although the United States’ tax rate reduction in 2017 occurred during a Republican administration, in other countries where tax rates have come down, they’ve done so under left-leaning governments. This is a phenomenon relating to something more fundamental than the politics of the day: the change in the world economy over this period.

A Changing Economic Setting

A good way to illustrate what’s happened in the world economy, in particular in the US economy, is to compare the list of the largest US companies 50 years ago and today. Fifty years ago, the top five companies by market capitalization were IBM, General Motors, AT&T, Standard Oil of New Jersey (Esso, the predecessor of today’s ExxonMobil), and Eastman Kodak. (Although these names are mostly still familiar, one should remember that AT&T wasn’t the AT&T of today, but rather the enormous regulated monopoly, “Ma Bell,” which provided local and long-distance telephone services and also manufactured and provided telephones.) These were companies that “made things” in identifiable locations, to a large extent in the United States. If we shift to today, we see another five familiar names, all giant companies: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet (Google’s parent), and Facebook. These companies are worldwide multinationals, relying very heavily on the use of intellectual property in the goods and services they provide.

To highlight how things have changed, some statistics are also helpful. In the last half century, the share of intellectual property measured in US nonfinancial corporate assets more than doubled, according to the Fed’s Financial Accounts of the United States.3 That’s probably a conservative estimate, because the measurement of intellectual property is a fairly narrow one here. The share of before-tax US corporate profits coming from overseas operations nearly quintupled, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.4 US companies have become much more multinational in character, not just selling things abroad, but making them abroad as well. And the share of cross-border equity ownership has steadily increased, to the point that foreign individuals and companies account for a significant fraction of US companies’ share ownership.5

What do these changes imply for tax policy? First, there is increased pressure on tax systems that are based on corporate residence. It’s natural to think of individuals as residents of particular countries, but our income tax system also identifies corporations by where they reside. In 1971, it may have been pretty obvious what a US company was, in terms of who owned the company and where it produced. That’s much less true now. There is much greater multinational activity of companies that legally reside in the United States, and they have many more shareholders abroad as well. These two factors make it easier to engage in so-called corporate “inversion” — that is, to change the corporate residence through corporate reorganization — which a company might want to do if being a resident of a particular country, such as the United States, is disadvantageous from a tax perspective.

The second implication for tax policy is increased pressure on tax systems based on where companies produce. The location of production is easier to change now because companies have internal supply chains; they’re producing around the world already. So if they want to shift production from one location to another, they have existing operations to make that easier. Moreover, because they’re producing things like microchips and pharmaceuticals and, indeed, services, rather than heavy things like autos and steel, they don’t have to worry about location as much in terms of transportation costs.

Finally, there is increased pressure on tax systems based on where companies report their profits, as distinct from where they produce. We normally think of companies as earning profits where they produce, but one of the problems governments face today is that companies may produce in one location and report the profits deriving from that production in another. It’s easier now for companies to shift profits in this manner because they have operations in so many countries, and it’s particularly easy when the income is being generated by intellectual property because intellectual property has no easily identifiable location. We may know where a factory is, but it’s a lot harder to say where a piece of intellectual property is, or is being used in production.

I should add one qualification. Many estimates in the recent literature have suggested that profit shifting is occurring on a vast scale. At least some of these estimates may have overstated the extent of profit shifting, according to analysis by Jennifer Blouin and Leslie Robinson, because of double-counting and other difficulties involved in interpreting government data.6 Nevertheless, the increased capacity for shifting profits to low-tax countries remains an important issue, one that certainly drives thinking about tax reform.

So we have a situation where existing tax systems — the ones traditionally used for decades in the United States and elsewhere to tax corporations based on where corporations reside, where they produce, and where they earn their profits — seem unstable and ill-suited to the evolving world economy. What are the options for reform? Several approaches have been tried, and others have been proposed.

The most common approach to dealing with the problems of traditional tax systems involves so-called “anti-avoidance” rules. Tax officials implement specific provisions aimed at restricting the range of transactions in which companies can engage to shift profits — for example, the extent to which they can use related-party borrowing to generate interest deductions in high-tax countries. But such mechanisms also have adverse effects from the adopting country’s perspective. Simply put, if you make it harder for a company that’s producing in the United States to report profits in a lower-tax country, that shifts taxable profits back to the United States, but at the same time increases the effective tax rate that the company faces on its US activities and may make its production decisions more sensitive to the US tax rate.7 Likewise, the United States has been trying to come up with rules to limit inversions, but these rules are becoming increasingly complicated as corporations devise different strategies for changing residence.

A second approach that has been used, especially in Europe, has been to implement so-called “patent boxes” — favorable regimes for intellectual property. The idea is that if income associated with intellectual property is particularly sensitive to tax rates and typically difficult for tax authorities to locate, then governments should impose lower tax rates on such income, essentially conceding that they’re not going to be able to impose a higher tax rate. Governments also justify such favorable regimes with the argument that intellectual property development and use may have positive productivity spillovers in other parts of the economy. One problem with patent boxes is that, in a sense, they deal with tax competition by simply giving up. Also, research suggests that companies are responding to these favorable regimes by locating intellectual property income in favorable places, but not necessarily doing the kind of research and development in those places that would be associated with productivity spillovers.8 So this doesn’t appear to be a fundamental solution to the problem of tax competition either.

Third, starting in Europe but spreading more broadly, a series of recent proposals and policies have targeted big, largely US tech multinationals with new, separate taxes on receipts based on where companies’ users are. The rationale for such taxes is that companies like Google or Facebook have lots of users in the countries in question, but by traditional income tax rules lack what is referred to as nexus in those countries: they don’t engage in any traditional production operations there. By standard income tax rules, the companies owe little or nothing under these countries’ income taxes, so individual countries, and indeed the European Union collectively, have pursued an ad hoc solution — digital service taxes (DSTs) based on where users are.

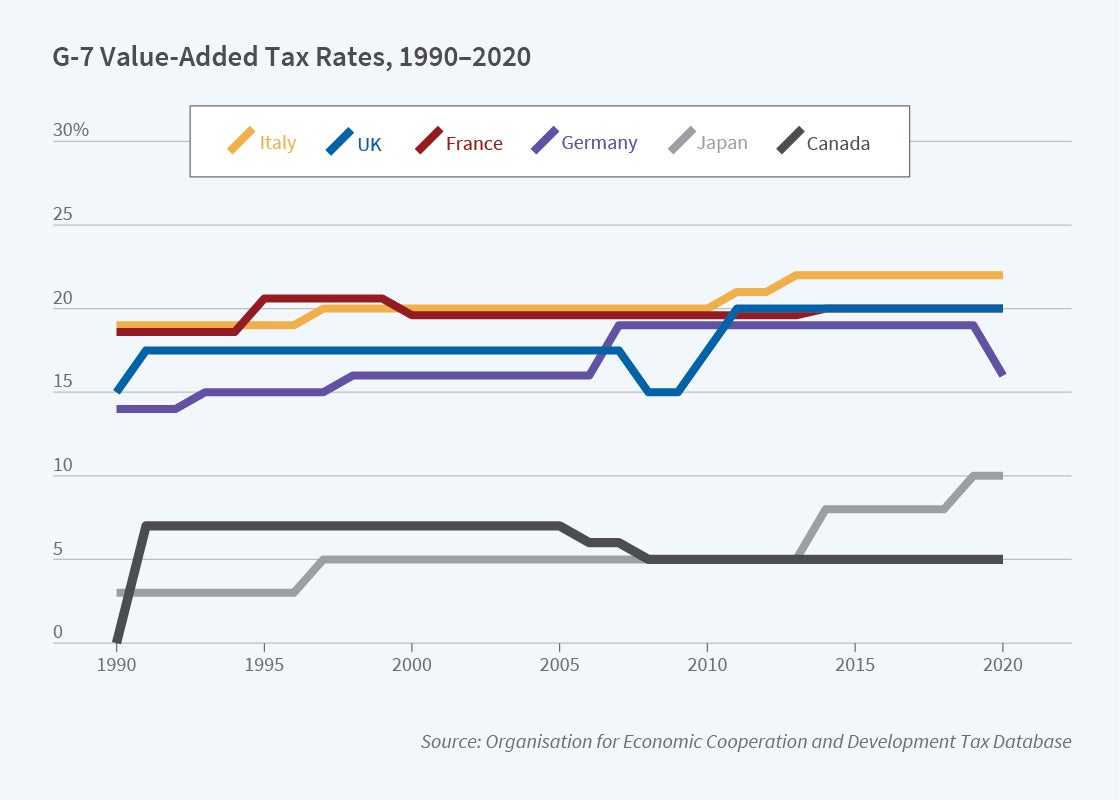

A fourth type of response to the difficulties of traditional taxation approaches is to adopt destination-based taxes, in some sense what DSTs do but in a much more fundamental way. The idea is to tax companies based not on where they reside, where they report their profits, or where they produce, but on where their sales are, because consumers are relatively immobile. A tax based on destination is likely to be less susceptible to competition over tax rates among countries because competing for corporate residence, production, or profits is likely to be much more intense than trying to get people to move across borders to take advantage of lower tax rates. The main existing tax based on destination, the value-added tax, unlike the corporate tax, shows little susceptibility to tax rate competition, as this corresponding figure for the G7 shows. (Of course, there are only six countries represented here because the United States, alone among the G7 and indeed among developed countries, does not have a value-added tax or any national consumption tax.)

There is no obvious downward trend in VATs, and indeed some of the downward blips represent countercyclical policies, such as by the United Kingdom during the global financial crisis. This difference in trends arises not because the VAT is a tax on consumption rather than a tax on income, but because it’s a tax based on destination rather than on the location of earnings, production, or corporate residence.

Because of the reduced focus on residence and the location of profits or production, the unilateral adoption of destination-based taxes by one country might actually push other countries in the same direction. If the United States, for example, were to move to a corporate tax based on destination, it would encourage more companies to produce and report their profits in the United States because they would no longer be subject to tax based on those actions; that might pressure other countries to follow suit. This interaction would be a form of tax competition, but it doesn’t require a low tax rate, simply a different kind of tax base, and reflects an important and overlooked objective of international tax policy, in addition to all the other things we’d like tax systems to satisfy, such as economic efficiency, equity, and ease in administration: incentive compatibility, that is, countries perceiving it to be in their own best interest to adopt a tax system without having to be coerced by others.

The advantages of destination-based taxation and the importance of incentive compatibility in international tax reform are emphasized in the book Taxing Profit in a Global Economy that several collaborators and I recently published.9 In this book, produced over a period of several years, we analyze two specific proposals, one big, one small in terms of the magnitude of changes from the current system. The small one would tax residual profits based on the location of sales income, which we call Residual Profit Allocation by Income (RPAI). The large one is a Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax (DBCFT), which received serious consideration in the United States a few years ago. Let me explain each proposal in a bit more detail.

The RPAI is a hybrid system. For routine operations involving traditional production using tangible assets and likely not earning a particularly high rate of return, the old system probably still works pretty well, and the plan would continue to tax such earnings based on where companies report that they are producing and earning profits. But for many companies, especially the biggest US companies, a lot of residual earnings will remain after these “routine” profits are taken out. These residual earnings would be allocated based on the location of net sales revenues. This is a partial apportionment system; apportionment is familiar for those of us in the United States from the way that states tax corporate income. An interesting development among the US states has been the steady movement over the years toward apportionment based on sales — rather than payroll or assets — with no coercion or coordination. That states have chosen destination independently confirms the idea of incentive compatibility for this approach.

The DBCFT would impose a cash-flow tax on domestic operations. It would also implement border adjustments, eliminating the import deduction and the tax on exports. These border adjustments would work precisely as they do under existing value-added taxes. Border adjustment accomplishes two things. First, it shifts the location of the tax base from production to consumption. Commodities consumed in the United States would be taxed in the United States even if produced elsewhere, and those produced in the United States but consumed elsewhere wouldn’t be taxed in the United States. But of equal importance, border adjustment would eliminate profit-shifting opportunities because transactions with related parties in other countries would not be part of companies’ tax calculations.

Although structured as a tax on business income, the DBCFT is equivalent to a value-added tax but with one important difference: it doesn’t tax the wage and salary component of value added, making it a tax on profits rather than a tax on value added. This difference makes the DBCFT much more progressive. Indeed, one can show that the destination-based cash-flow tax is equivalent to a one-time tax on the wealth of residents through a tax on the future cash flows that they receive.10

As already mentioned, the DBCFT was proposed in the United States in 2016 during the discussion leading up to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) passed in 2017. It was not implemented because of several concerns, including the short-run effects associated with exchange rate adjustment, possible World Trade Organization reaction, given the focus of WTO rules on form over substance, and, alas, a general lack of understanding of the proposal’s economic effects, including a continuing failure to comprehend the point made by Feldstein and Krugman that border adjustment is not a trade-distorting policy.

Finally, we have what the United States did enact in 2017, which follows something of a “kitchen sink” approach. The TCJA contained a little bit of everything. It reduced the corporate tax rate, thereby continuing tax competition. It introduced some additional tax avoidance measures, including a global minimum tax on US companies, on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), taxing income earned abroad by US companies if that income faced a low rate of tax. It introduced investment expensing and narrowly targeted border adjustments on exports and imports, thus borrowing from the DBCFT.

The TCJA didn’t have a unified logical basis. It also did not produce a stable situation, for the United States or the world. It generated a tax revenue loss that the United States can ill afford. It discourages US corporate residence because the minimum tax was adopted by the United States alone, and therefore could be avoided by not being a US resident company. Finally, there was no measure in the TCJA to deal with digital services, which will not leave other countries happy with the outcome.

The Two Pillars

The foregoing review of the various approaches tried or considered brings us to where we are now, which is the initiative that has taken place over many years, started by the OECD and reflected in a specific proposal this year known as the Two Pillars. I have to pause here and note that I have not been educated to think about the tax system as having pillars, although I suppose the idea is that these two pillars are going to hold up the world tax structure. For me, unfortunately, a different picture comes to mind, based on a familiar story from the Old Testament, in which the two pillars fail: those that Samson pushes apart to bring down the temple on his tormentors, the Philistines. If one continues this analogy a little further and thinks about who Samson is in this situation (leaving aside who the current Philistines are), perhaps it might be the Republic of Ireland or one of the other countries that have not yet signed on and become a member of the “coalition of the willing” in this initiative.

How would the two-pillar approach work? Pillar 1 is essentially a replacement for digital service taxes. It would allocate to market countries a fraction of profits of extremely large companies, above a threshold. Specifically, 20 to 30 percent of profits above 10 percent of sales revenues would be taxable for those companies (excluding those in financial services and resource extraction) with over 20 billion euros a year in annual revenues. Pillar 2 would be a global minimum tax, along the lines of what the United States adopted in 2017, with some important differences. It would be at a rate of at least 15 percent imposed above a threshold of 7.5 percent of tangible assets plus payroll for multinationals with more than 750 million euros in annual revenues. Pillar 2 also includes some other provisions to encourage adoption by imposing penalties on those countries not doing so.

Regarding Pillar 1, estimates suggest that if the aim is to target large US multinationals, it is successful in doing so. These estimates are that close to two-thirds of global tax revenues would be generated by US companies, and half of that amount would come from five companies: Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Intel, and Facebook.11 While Pillar 1 does introduce the idea of destination-based taxation in a manner similar to the RPAI plan discussed above, it is much more limited in scope. It only applies to a small number of extremely large tech companies and allocates only 20 to 30 percent of excess profits rather than all. However, one might think of this as the first step in the direction of adopting the principle more broadly, a point to which I will return.

Pillar 2 is a bit like the US GILTI provision, but it would be tougher because it would impose a higher tax rate. On the other hand, it doesn’t go as far as a proposal put forward by the Biden administration earlier this year, which would have had a tax rate of 21 percent and no threshold over which taxes would be assessed. By taxing even “normal” returns in low-tax countries, the Biden approach was aimed not just at companies shifting profits to low-tax countries, but also at companies shifting production activities themselves. It thus would have targeted a broader array of multinational activities.

We now come to two important questions. Can the agreement work? Should it work? In the short term, there are serious challenges to getting the system off the ground. Among these is whether the United States can get approval for renegotiated treaties needed to adopt Pillar 1, ceding the right to tax income to destination countries. Though the Biden administration has expressed support for Pillar 1, it would also need the support of two-thirds of the Senate for treaty approval. As many countries have agreed to Pillar 2 in order to gain adoption of Pillar 1, a US failure to adopt Pillar 1 could lead to a loss of support elsewhere for Pillar 2. A second short-term question is whether the United States can get the proposed minimum tax through the budget reconciliation process, which would require 50 votes in the US Senate. And finally, can Europe achieve unanimity? Without it, certain elements of the plan could not be imposed on other members of the European Union, and as of now three EU members — Estonia, Hungary, and Ireland — have not signed on.

But beyond the immediate hurdles facing adoption, there is also a more fundamental, longer-term challenge arising from the attempt to preserve a tax system based on concepts that don’t really work anymore, that are ill-defined and endogenous: corporate residence and the location of production and profits (something that tax authorities have taken to referring to as the location of value creation). Because it relies on these ill-defined concepts, the two-pillar system is not going to be sustainable unless countries adopt and adhere to similar rules that lessen incentives for companies to shift production, profits, and residence.

What does this outcome require? It requires that countries adopt similar minimum tax rates and bases across home countries (so that the base and the rate together provide similar effective tax rates), to lessen the incentives for companies to shift corporate residence, as residence determines which minimum tax applies. Also needed are similar regular corporate tax rates and tax bases among the countries, to prevent companies from shifting their production and profits location from one country to another in cases where the minimum taxes do not apply. Finally, it is necessary for any given country to have similar regular and minimum tax rates and bases to keep companies that are resident in those countries from shifting their profits and their production abroad. This is relevant, for example, for the United States, which has agreed to a 15 percent minimum tax, with the Biden administration currently proposing a 28 percent tax rate on domestic income.

What should determine these similar tax rates and tax structures? There has been so much focus on the objective of limiting tax competition that one can easily lose sight of the fact that limiting tax competition isn’t the only major objective of tax policy. There are many other objectives as well that can help determine whether the corporate tax rate should be, say, 21 percent, 28 percent, or 35 percent; whether the minimum tax rate should be 15 percent or 21 percent, as the Biden administration originally proposed; and whether the tax base should have a threshold or not. These are questions that can only be answered if one thinks about what governments are trying to achieve, for example how much revenue they are trying to raise and the extent to which they seek to encourage saving and investment. These questions are not addressed simply by agreeing to coordinate on policy, and different countries likely will have different objectives that push in different directions, toward differences in tax rates, tax bases, and minimum taxes. Had the two-pillar framework focused less on trying to preserve the existing system and more on moving in the direction of destination-based taxation, governments could have pursued different objectives without worrying about tax competition. For example, had the United States adopted the DBCFT in 2017, it could have kept its 35 percent corporate tax rate and would not have needed to adopt a global minimum tax.

So where does that leave us? I will not make the mistake of trying to predict what happens in the short run, i.e., how far we get with Pillars 1 and 2 and the proposed international agreement. But over the longer term, whatever the short-run success in getting this agreement adopted widely, there will continue to be pressures of the type I just discussed for countries to move in opposite directions. Part of the movement that results likely will be in the direction of destination-based taxation. I mentioned earlier that the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act included certain pieces taken from the DBCFT. The incentives for policymakers to include such provisions remain and will continue to be a part of the tax policy process. For example, it’s quite possible that Pillar 1, although very narrow as proposed, may eventually be expanded. As countries see that it works pretty well, they may want to lower its size threshold so that it applies to a much larger group of companies, and to increase the share of profits allocated in this manner. Or, they may increase their VATs, which, with compensating reductions in labor income taxes, simulates gradual adoption of the DBCFT. Changes like these do not require international coordination.

Whatever form it takes, such movement toward destination-based taxation will not only provide more tax revenue, it will also lessen the need for minimum taxes, which are, after all, aimed at enforcing taxes based on traditional approaches. One consequence is likely to be further pressure on minimum taxes, as countries moving toward destination-based taxation see them as no longer needed to provide revenues or protect their tax bases. In short, whatever the world’s tax landscape in the near future, one should expect a continuing evolution toward a tax system that is more logical and self-sustaining.

Support for the 2021 NBER Summer Institute, which included this lecture, was generously provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Harry and Lynde Bradley Foundation, and the National Science Foundation (grant 1851757).

Endnotes

“The Optimal Taxation of Foreign Source Investment Income,” Feldstein M, Hartman D. NBER Working Paper 193, November 1980, and Quarterly Journal of Economics 93(4), November 1979, pp. 613–629.

“International Trade Effects of Value-Added Taxation,” Krugman P, Feldstein M. NBER Working Paper 3163, November 1989, and in Taxation in the Global Economy, Razin A, Slemrod J, editors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

“Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” Rosenthal S, Burke T. Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, October 2020.

“Double Counting Accounting: How Much Profit of Multinational Enterprises Is Really in Tax Havens?” Blouin J, Robinson L. April 2021, SSRN.

See, for example, the evidence presented in “At a Cost: The Real Effects of Thin Capitalization Rules,” De Mooij R, Liu L. Economics Letters 200, March 2021.

“Should There Be Lower Taxes on Patent Income?” Gaessler F, Hall B, Harhoff D. NBER Working Paper 24843, June 2019, and Research Policy 50(1), January 2021.

Taxing Profit in a Global Economy, Devereux M, Auerbach A, Keen M, Oosterhuis P, Schön W, Vella J. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021. The volume may be downloaded at https://oxfordtax.sbs.ox.ac.uk/files/tpiage-full-text-9780192535573pdf.

“Consumption and Cash-Flow Taxes in an International Setting,” Auerbach A, Devereux M. NBER Working Paper 19579, October 2013, and published as “Cash-Flow Taxes in an International Setting,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(3), August 2018, pp. 69–94.

“Who Will Pay Amount A?” Devereux M, Simmler M. Policy Brief 36, European Network for Economic and Fiscal Policy Research, July 2021.