Household Expectations: From Neuroscience to Household Finance and Macroeconomics

Recent work in neuroscience and neuroeconomics has provided valuable insights into the factors that drive individuals' formation of expectations. These insights can be used by economists to better understand individuals' beliefs and behaviors. Moreover, aggregate-level implications can be drawn from these micro-level findings.

Neuroscientist Brian Knutson and I documented an asymmetry in the brain in the processing of gain and loss information.1 This discovery of asymmetric encoding of positive and negative outcomes led to a hypothesis that could be tested experimentally in the context of financial decision-making. In experiments conducted in three countries — the United States, Romania, and Germany — I have found that learning occurs differently depending on whether gain or loss has taken place. Specifically, negative outcomes induce overly pessimistic beliefs about investment payoffs.2 This is because, in an environment characterized by negative payoffs, people put too much weight on each additional bit of bad news. This experimental finding suggests that, at the aggregate level, recessions could last longer and be more severe than predicted by standard models, in part because of undue pessimism among individuals.

Participants in my experiments were temporarily exposed to environments characterized by only positive or only negative payoffs; they exhibited a clear bias toward pessimism in learning in the loss domain. Outside of the laboratory, however, many people have encountered negative outcomes on a regular basis, experiencing significant adversity. Do they process information about economic outcomes differently than others in the same age cohort, with the same macroeconomic history? Neuroscience suggests that to be the case. Specifically, it has been shown that experiencing adversity shapes the way the brain learns, so that there is an increased neural sensitivity to loss information and a decreased neural sensitivity to gain information.3 In recent research, Sreyoshi Das, Stefan Nagel, Andrei Miu, and I find in laboratory experiments as well as in large survey data that people who have encountered more adversity, measured by socioeconomic status (SES), form more pessimistic beliefs about financial investments and economic opportunities and avoid investing in stocks or real estate. Controlling for participants' prior beliefs and the information they possess regarding investment options, Miu and I find that lower-SES individuals update less from high asset payoffs than their higher-SES counterparts, and end up with more pessimistic beliefs about the quality of these assets. As a result, lower-SES individuals are less likely to invest in these assets, particularly at times when, objectively, the assets can be expected to have high payoffs.4

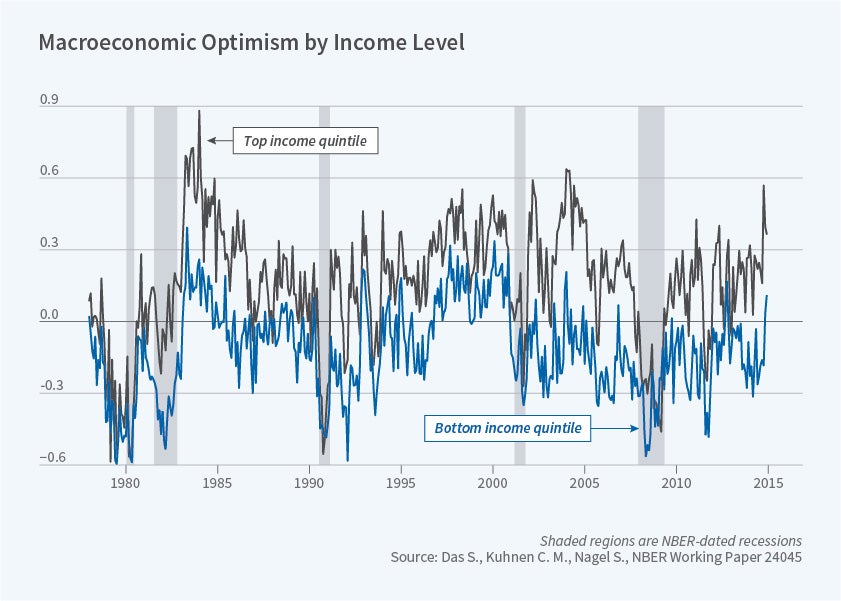

While lab experiments allow researchers to test hypotheses in controlled environments, there is always a question about the external validity of lab findings. To investigate whether it is generally true that those with lower incomes or lower education have overly pessimistic beliefs about financial investment opportunities, as well as about macroeconomic conditions in general, Das, Nagel, and I use data from the University of Michigan's Surveys of Consumers (MSC). We use monthly data over 38 years with about 180,000 person-month observations. The data include SES measures (i.e., income rank in the respondent's age bracket, as well as education), five macro-expectations measures, including beliefs about future stock market returns or the national unemployment rate, as well as self-reported household choices such as equity investments or the purchase of homes, durables, or cars. The large- scale evidence we find using the MSC is consistent with the experimental findings. Namely, we find that higher-SES individuals are more optimistic about the macro-economy relative to lower-SES individuals, but that in recessions, this expectations gap narrows dramatically.5 [Figure 1]

While it has been known that SES measures like income and education matter for financial choices — for example, households earning higher incomes are more likely to participate in the stock market — using data from the MSC, we document that part of the link between SES and household choices can be attributed to the expectations channel. That is, about 20 to 30 percent of the effect of income or education on choices such as investing in equities or buying a home is driven by the fact that higher-SES individuals are more optimistic about macroeconomic conditions. The aggregate implication of this finding is that pessimistic macroeconomic expectations held by lower-SES individuals are part of the reason these individuals stay away from risky financial investments and as a result accumulate low levels of wealth, whereas higher-SES individuals hold optimistic beliefs and make investments with high expected returns. Over time, this may lead to an increase in wealth inequality. It remains to be seen whether the same patterns of differential expectations by SES level, as well as differential levels of investment because of these expectations, also affect investments in education or human capital, or the decision to engage in entrepreneurial pursuits.

Adversity does not just impact the lens through which individuals view economic opportunities in a glass half-full versus glass half-empty manner. It also impacts perceived uncertainty about the economic environment. This idea comes from work in cognitive science and neuroscience that shows that life adversity, which is characterized by environmental instability, influences learning. Specifically, individuals faced with adversity perceive that the overall environment is volatile.6

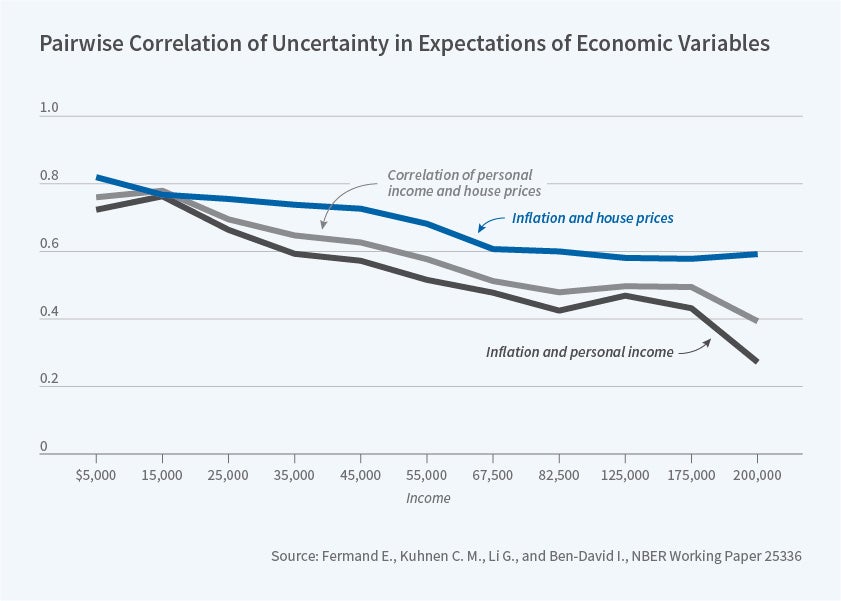

In a recent study, Elyas Fermand, Geng Li, Itzhak Ben-David, and I find that lower-SES individuals are more uncertain in their micro- and macro-level economic expectations, and, all else being equal, more uncertain individuals engage in more cautious behaviors.7 We use data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) covering more than 1,200 households each month, 2013 to 2017. Respondents report their expectations about three variables: their personal income growth, the national inflation rate, and the rate of growth of national home prices over the upcoming 12 months. The elicitation procedure captures information about the mean outcome that each respondent expects, as well as the uncertainty associated with that expectation. We find that individuals with lower income and education levels, facing more precarious financial conditions or living in counties with higher unemployment, report more uncertainty about their expectations.

Drawing on objective measures of uncertainty derived from the volatility of aggregate inflation and national home price growth, we find that lower-SES individuals report distributions of expectations that are more diffuse — "wider" — than the objective distributions. Furthermore, we find that if a person reports more uncertainty about one of the three economic variables in the survey, they are also more likely to report more uncertainty for the other two variables. This effect, the extrapolation of uncertainty across domains, is particularly strong among low-SES individuals. [Figure 2.] We also find that uncertainty in economic expectations influences behavior in ways consistent with prior theories: All else equal, those with higher uncertainty regarding economic outcomes are more likely to engage in precautionary behaviors in terms of consumption, credit, and investment decisions, in that they plan to lower their consumption, seek additional lines of credit, and invest less in equities.

Our findings suggest that it is important to understand which households are more uncertain in their expectations, as this uncertainty can impact responses to policy changes targeting expectations and behavior. The fact that lower-SES individuals and those from communities with worse economic conditions are the most uncertain suggests that a reduction of uncertainty would have a higher impact on the decisions of these individuals than on the decisions of those who are better off.

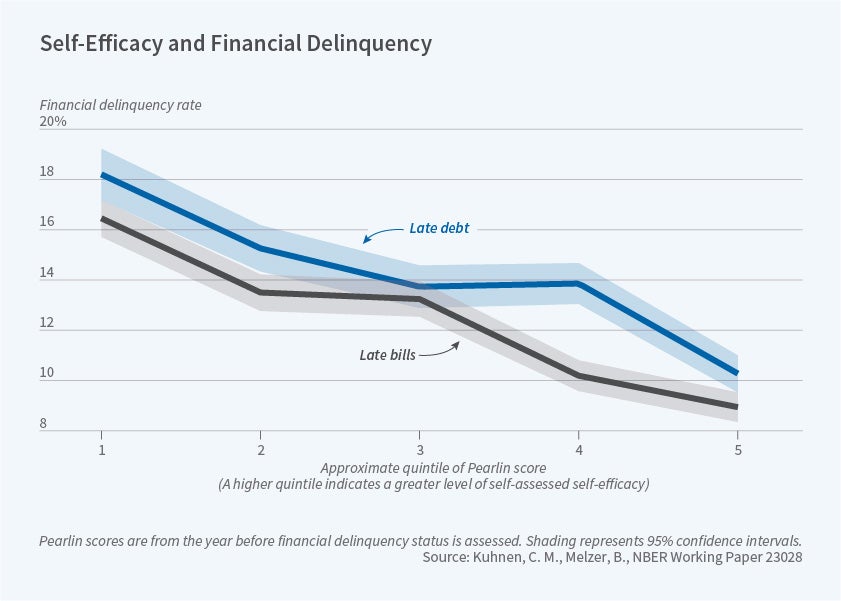

Lastly, neuroscience work has documented heterogeneity regarding the brain's response to adversity. Specifically, self-efficacy modulates the ability to deal with negative shocks.8 Self-efficacy is a personal characteristic that captures the strength of an individual's belief that his or her actions can influence the future. Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Child and Young Adult sample (NLSY79CYA) of about 6,000 individuals tracked from their teens to adulthood, for whom we have detailed financial information in 2010, 2012, and 2014, as well as measures of self-efficacy earlier in life, Brian Melzer and I find that people who have high self-efficacy scores are more likely later on to avoid being financially delinquent, in the sense of missing debt payments or bill payments, especially when hit by shocks such as a health issue or the loss of a job.9 [ Figure 3.] As a result, lower self-efficacy individuals are more likely to lose access to traditional credit markets and to lose assets through bankruptcy and foreclosures. Those with higher self-efficacy put in more effort to protect themselves against potential shocks, for example, through insurance or emergency savings, and when negative shocks occur, they have a lower chance of experiencing financial distress. We find that the beneficial effect of having high self-efficacy in terms of avoiding financial distress is triple in size for individuals who have faced economic adversity early in life, as measured by having a mother who was in the lowest third of the population in wealth, relative to the effect observed among those whose mothers' wealth was in the top third. The broad implication of these findings is that non-cognitive skills, including having positive expectations about one's ability to influence one's future, can shape the financial health of populations. Such expectations are particularly beneficial for individuals coming from lower-SES backgrounds, where traditional financial products or intrafamily insurance may not be available to cushion the effects of negative economic shocks.

We still have a lot to learn about why households differ in their expectations about economic variables that can influence their consumption or wealth down the road. The data we have so far indicate that these expectations are predictable to some degree, and that a lot of these predictions can be informed by work done in other academic disciplines, such as neuroscience and psychology. Household expectations affect many household economic decisions, and are critically important determinants of the impact of various public policies. Further investigation is needed to understand both their drivers and their consequences.

Endnotes

"The Neural Basis of Financial Risk-Taking," Kuhnen C, Knutson B. Neuron, 47(5), September 2005, pp. 763–770.

"Asymmetric Learning from Financial Information," Kuhnen C. Journal of Finance, 70(5), October 2015, pp. 2029–2062.

"Cumulative Stress in Childhood Is Associated with Blunted Reward-Related Brain Activity in Adulthood," Hanson J, Albert D, Iselin A, Carré J, Dodge K, Hariri A. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(3), March 2016, pp. 405–412.

"Socioeconomic Status and Learning from Financial Information," Kuhnen C, Miu A. NBER Working Paper 21214, May 2015, and Journal of Financial Economics 124(2), May 2017, pp. 349–372.

"Socioeconomic Status and Macroeconomic Expectations," Das S, Kuhnen C, Nagel S. NBER Working Paper 24045, November 2017, and forthcoming in Review of Financial Studies.

"Rational Snacking: Young Children's Decision-making on the Marshmallow Task is Moderated by Beliefs about Environmental Reliability," Kidd C, Palmeri H, Aslin R. Cognition, 126(1), January 2013, pp. 109–114.

"Expectations Uncertainty and Household Economic Behavior," Fermand E, Kuhnen C, Li G, Ben-David I. NBER Working Paper 25336, December 2018.

"Affective State and Locus of Control Modulate the Neural Response to Threat," Harnett N, Wheelock M, Wood K, Ladnier J, Mrug S, Knight D. Neuroimage 121, November 2015, pp. 217–226.

"Non-Cognitive Abilities and Financial Delinquency: The Role of Self-Efficacy in Avoiding Financial Distress," Kuhnen C, Melzer B. NBER Working Paper 23028, January 2017, and Journal of Finance, 73(6), December 2018, pp. 2837–2869.