Trends in Factor Shares: Facts and Implications

The distribution of national income between capital and labor and the determinants of that split are important for many reasons. The evolution of factor shares over time affects income inequality across households. Changes in factor shares inform economists' assumptions about aggregate production technologies and their understanding of the state of product and labor markets. The behavior of factor shares influences conclusions about the implications of progress in computing, robotics, and information technologies, the response and incidence of changes in tax policies, and the dynamics of markups and competition.

For many decades, the assumed stability of factor shares — one of the "stylized facts" about growth codified by Nicholas Kaldor in 1961 — meant that the modern macroeconomics literature paid little attention to trends in the functional distribution of income.1 Measurement challenges and the absence of long time series for more than a small set of countries likely also played a role in dampening economists' interest in the evolution of factor shares over time.2

The Global Decline of the Labor Share

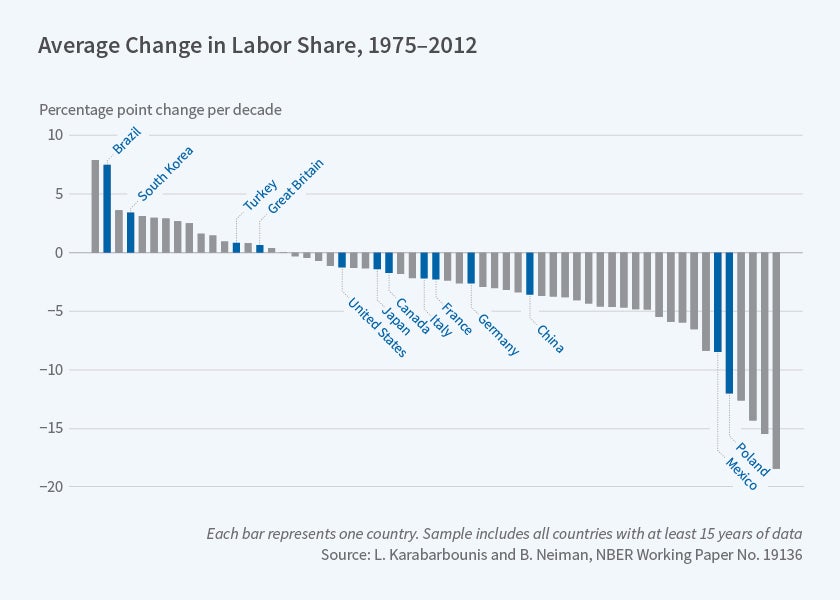

Our work builds on a dataset that we collected from national income and product accounts for many countries and industries. We demonstrate that, at the global level, the labor share has been declining since the early 1980s.3 The decline has been broad-based. As shown in Figure 1, it occurred in seven of the eight largest economies of the world. It occurred in all Scandinavian countries, where labor unions have traditionally been strong. It occurred in emerging markets such as China, India, and Mexico that have opened up to international trade and received outsourcing from developed countries such as the United States.

Where available, we use the labor share of income in the corporate sector as our preferred measure of the labor share, as it excludes many unincorporated enterprises and sole proprietors whose income is difficult to split between labor and capital. Further, our measure is not influenced by the government sector, which lacks market prices for its output, or by the residential sector (that has a labor share of zero), whose share of the total GDP fluctuates for reasons potentially unrelated to technology or product market structure.4 We have posted our country-level data set online and it has been used in a number of studies.

The labor share declines occurred in most U.S. states and, globally, in most industries, including manufacturing, wholesale, and retail. Some have suggested that the share of compensation in domestic product net of depreciation, rather than in gross domestic product, is more informative about inequality between workers and capitalists. In fact, while some exceptions exist, most notably the United States, most countries experienced similar trend declines in their labor shares regardless of whether the share is measured as a fraction of net or gross domestic product.5

Possible Explanations

The labor share decline likely has multiple drivers. A key benefit of our focus on the global decline is that it restricts the set of explanations to those that operate on a global scale. Country-specific changes in policies, for instance, might be important for specific countries but are unlikely to account for much of the overall trend that the world has experienced.

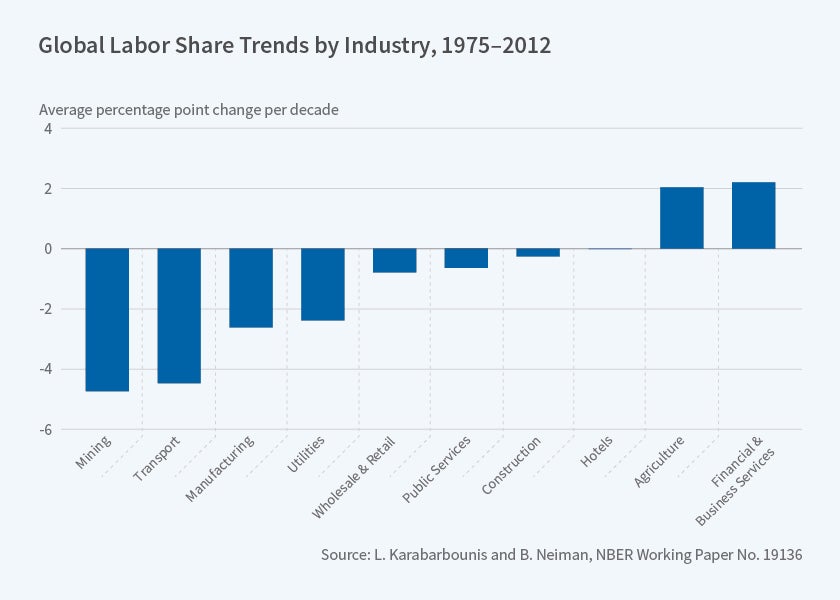

Global trends in the value-added shares of various industries, referred to as structural change, contribute to the decline in the labor share if industries with lower labor share levels have grown relative to industries with higher labor share levels. Most of the labor share decline — and most of the cross-country variation in the labor share decline — is due to within-industry declines.

Another possible force contributing to the decline in the labor share is the substitution away from labor and toward capital in production. There was a decline in the price of investment relative to consumption that accelerated globally around the same time that the global labor share began its decline. A key hypothesis that we put forward is that the decline in the relative price of investment, often attributed to advances in information technology, automation, and the computer age, caused a decline in the cost of capital and induced firms to produce with greater capital intensity. If the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor — the percentage change in the capital-labor ratio in response to a percentage change in the relative cost of labor and capital — is greater than one, the lowering of the cost of capital results in a decline in the labor share.

Most prior estimates of the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor are based on time series variation within a country in factor shares and factor prices. These estimates generally imply an elasticity of substitution below one. By contrast, our estimates of this elasticity are identified from cross-country and cross-industry variation in trends in labor shares and investment price declines. We find that countries and industries with larger declines in investment prices experienced larger declines in their labor shares, which leads to our estimate of an elasticity of substitution equal to 1.25. Taken together with the observed decline in the relative price of investment, our estimates imply that this form of technological change accounts for roughly half of the decline in the global labor share.6

This elasticity — and the implied relationship between capital-biased technical change and the labor share — applies at the industry or country level and is therefore inclusive of changes in economic activity across firms within industries or across firms and industries within countries. Our hypothesis that progress with IT-related technologies has contributed to the decline in the labor share is, therefore, not inconsistent with the possibility that most firms experience stable or even rising labor shares, while low labor share firms gained in market share.7

We also demonstrate how the inclusion of multiple types of capital with heterogeneous depreciation rates complicates the relationship between labor shares and the user cost of capital. Further, while a single elasticity suffices to relate trends in the labor share to trends in the user cost of capital when all capital can be bundled into a single type, this will not be the case for production functions with different nesting of capital types and labor, such as those posited in the literature on capital-skill complementarity.8 Our continuing work aims to further explore these issues.

If technology explains half of the global labor share decline, what might explain the other half? We use investment flows data to separate residual payments into payments to capital and economic profits, and find that the capital share did not rise as it should if capital-labor substitution entirely accounted for the decline in the labor share. Rather, we note that increases in markups and the share of economic profits also played an important role in the labor share decline.9

Other Implications

Beyond the conclusions about technology and product market structure that emerge, why else does the labor share decline matter? The evolution of the labor share is a useful summary statistic for consumption or welfare-based inequality between a representative worker and capitalist. Some analyses focus on the labor share in gross domestic product while others emphasize the labor share in net domestic product. Which of the two measures best approximates inequality depends on whether one studies transitional dynamics or the steady state, as well as which shocks are driving the labor share decline.

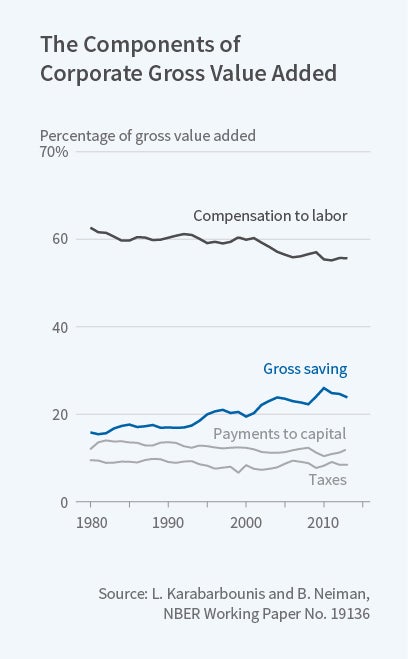

Our work also uncovers a closely related trend influencing the financing of global investment.10 Whereas in 1980 household saving funded most global investment, today corporate saving accounts for nearly two-thirds of every invested dollar. We measure corporate saving as undistributed corporate profits, which together with household and government saving equal national saving. We use a combination of aggregate and firm-level data to demonstrate that the decline in the global labor share resulted in an increase in accounting profits. Since dividends did not keep pace with profits, corporate saving increased.

The increase in corporate saving was also pervasive at the global level and observed in all ten of the largest economies. Further, given that global corporate investment has been relatively stable as a share of GDP since 1980, the corporate sector evolved from a net borrower to a net lender to the rest of the economy. The improvement in the net lending position of the corporate sector fell into various margins of adjustment, including reductions in debt, accumulation of cash, and equity buy-backs.

Next Steps

The stability of the labor share of income is a key assumption built into most modern macroeconomic models, but recent evidence shows downward trends in the labor share in the majority of countries and industries. Such trends are informative for the design of macroeconomic models, for evaluating changes in corporate financial practices, for assessing inequality, and for designing monetary and fiscal policies. A consensus remains elusive on the exact roles of factors such as technology, product market competition, globalization, and housing, and we are continuing our exploration of these issues in U.S. and international data.

Endnotes

Some notable exceptions include O. Blanchard, "The Medium Run," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 1997, pp. 89-158; O. Blanchard and F. Giavazzi, "Macroeconomic Effects of Regulation and Deregulation in Goods and Labor Markets," NBER Working Paper 8120, February 2001, and Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), August 2003, pp. 879–907; and C. Jones, "Growth, Capital Shares, and a New Perspective on Production Functions," Working Paper, 2003.

In thinking about the cross-section, for example, D. Gollin, "Getting Income Shares Right," Journal of Political Economy, 110(2), 2002, pp. 458–74, stressed the pitfalls in studying labor shares without a careful accounting for the mixed income earned by proprietors and unincorporated businesses. By the late 1990s or early 2000s, few countries had long and consistent time series that allowed for our preferred treatment of this income.

L. Karabarbounis and B. Neiman, "The Global Decline of the Labor Share," NBER Working Paper 19136, October 2013, and The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(1), February 2014, pp. 61–103.

While we view it as an improvement in this regard over the total labor share, see M. Smith, D. Yagan, O. Zidar, and E. Zwick, "Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century," Working Paper, 2017, for a discussion of why even the corporate sector's labor share is not fully isolated from the behavior of sole proprietors.

See L. Karabarbounis and B. Neiman, "Capital Depreciation and Labor Shares Around the World: Measurement and Implications," NBER Working Paper 20606, November 2014, and B. Bridgman, "Is Labor's Loss Capital's Gain? Gross Versus Net Labor Shares," Macroeconomic Dynamics, July 2017.

Similar conclusions are reached in analyses of a different global data set in "International Monetary Fund, "Understanding the Downward Trend in Labor Income Shares," World Economic Outlook, April 2017, pp. 121–72.

This pattern can be found in several firm or plant-level analyses of U.S. data, including D. Autor, D. Dorn, L. Katz, C. Patterson, and J. Van Reenen, "Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share," NBER Working Paper 23108, January 2017, and American Economic Review Papers & Proceedings, 107(5), May 2017, pp. 180–5; B. Hartman-Glaser, H. Lustig, and M. Zhang, "Capital Share Dynamics When Firms Insure Workers," NBER Working Paper 22651, October 2017; M. Kehrig and N. Vincent, "Growing Productivity Without Growing Wages: The Micro-Level Anatomy of the Aggregate Labor Share Decline," Working Paper, 2017.

See P. Krusell, L. Ohanian, J.-V. Rios-Rull and G. Violante, "Capital-Skill Complementarity and Inequality: A Macroeconomic Analysis," Econometrica, 68(5), September 2000, pp. 1029–53.

See M. Rognlie, "Deciphering the Fall and Rise in the Net Capital Share: Accumulation, or Scarcity?," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 46(1), spring 2015, pp. 1–69; S. Barkai, "Declining Labor and Capital Shares," Working Paper, 2017; and J. De Loecker and J. Eeckhout, "The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications," NBER Working Paper 23687, August 2017, for work elaborating on this rise in economic profits as it relates to the labor share.

See P. Chen, L. Karabarbounis, and B. Neiman, "The Global Rise of Corporate Saving," NBER Working Paper 23133, March 2017, and Journal of Monetary Economics, 89, August 2017, pp. 1–19.