Pricing and Marketing Household Financial Services in Developing Countries

Retail financial institutions worldwide are facing greater competition and regulatory scrutiny. This makes it increasingly important for them to understand the drivers of consumer demand for basic financial services if they are to maximize profits, improve social impacts, and address public policy concerns. Researchers also need to understand these drivers in order to calibrate, shape, and test models in fields ranging from contract theory to behavioral economics to macroeconomics to basic microeconomics. Likewise, policymakers need to understand these drivers in order to sift through a plethora of potentially relevant theories and set appropriate regulations. Much of our research seeks to identify the effects of pricing and marketing on demand for short-term loan and savings products in developing countries.

Pinning down causal effects of financial institutions' pricing and marketing strategies is complicated by at least five issues. One is the classic social science problem: Relying on observational data is fraught with the risk that changes in price or marketing are correlated with other changes - in firm strategy, in the macroeconomy, in household budget constraints - that drive selection. This is a particular concern when estimating treatment effects from expanding access to financial products such as credit, savings, or insurance. A second issue, intimately related to the first, is low statistical power due to limited variation in key policy parameters. A firm making a single change to pricing, a product, or marketing is basically generating a single data point of variation. The effects of the single change are difficult to disentangle from other contemporaneous changes affecting the firm and its constituents. This is a particular concern for savings products, as compared to loans, since one-size-fits-all pricing is more common and direct marketing is less common with savings products. These two issues are the primary motivation for employing experimental methods.

A third complicating issue is that most measures of demand sensitivity - for example, demand elasticities - are not fundamental or unchanging parameters. We expect demand sensitivities to change with factors like competition, labor market conditions, and search costs. A fourth issue is that a firm's levers are rarely perfect representations of a single parameter. For example, variations in price, in particular, may be confounded by other factors changing simultaneously and may therefore lead to deceiving results if interpreted strictly as an estimate of demand sensitivity. A fifth issue is that strategy often requires an understanding of underlying mechanisms, while identifying mechanisms requires observing off-equilibrium behavior. For example, observing loan repayment and other borrower behaviors under atypical conditions can help test theories of asymmetric information or liquidity constraints.

We address these challenges using field experiments implemented by financial institutions in the course of their day-to-day operations. The partnering financial institutions randomly assign prices, communications, or access to products, generating variation that is uncorrelated with other factors that vary endogenously over time or people. This addresses Issue One above. The financial institutions randomize policies at the individual or neighborhood level in order to generate sufficient statistical power to identify causal effects. This addresses Issue Two. In some instances, the financial institutions' randomized policies are implemented across sufficiently different people or markets, and are in place for long enough or with varying lengths of time, that we can examine under what conditions demand varies. This addresses Issue Three.1 In another instance, we use variation in price and advertising content to explore how those two levers interact, addressing Issue Four.2 Lastly, through two-stage experimental designs, we have tackled typically unobserved behavior on loan repayment as well as returns to capital, which pertains to Issue Five.3

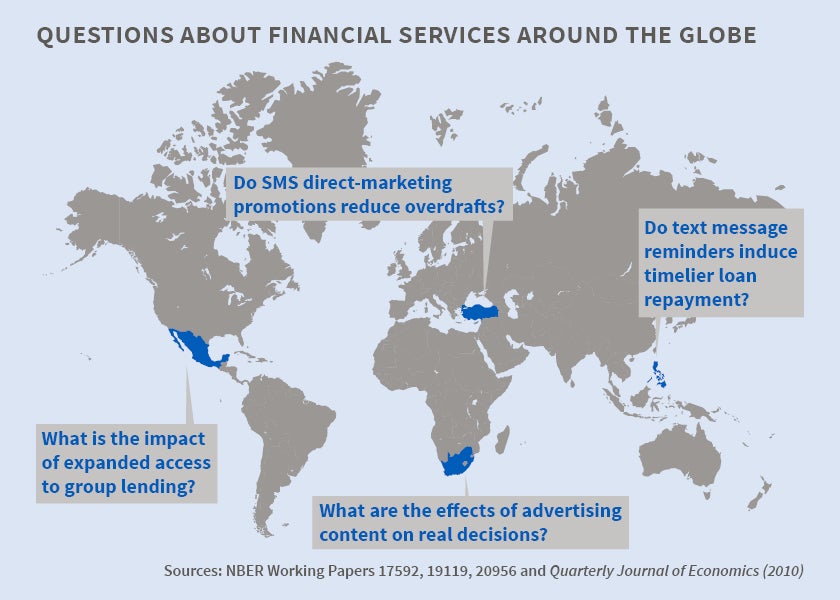

In our work,4 and in the work of others,5 we learn that financial markets for credit are not meeting the needs of the poor. In Mexico, the Philippines, and South Africa, we have found that financial institutions are able to expand access to microcredit by experimenting with risk-based pricing models or building offices in new geographic areas, effectively reducing the price of financial institution credit from infinity to a market rate for certain borrowers. Others have found the same to be true in Morocco, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mongolia, India, and Ethiopia. Indeed, every study of which we are aware that has examined the impacts of expanding credit supply has found that the expansion increased borrowing and did not merely crowd out other lenders. Similarly, financial institutions offering new-commitment savings products for 6-to-24 month savings goals have found take-up rates typically around 20–30 percent.6 Other financial institutions have found similar unmet demand for commitment savings.7

A second finding from the studies above is that the marginal consumers of basic financial services derive a variety of financial benefits from them. This is an important reality check, given concerns that various biases in household decision-making can lead to counterproductive borrowing.8 Beyond the basic reality check, the several studies that follow random assignment to loan or savings product availability with extensive household and microenterprise surveys have yielded surprising findings. On the credit side, the results have yielded little support for microcredit's great promise of poverty alleviation and social transformation. Rather, the benefits have been modest, and concentrated more in household risk management and flexibility than in profitable microenterprise growth.9 On the savings side, the first wave of impact evaluations has produced evidence of some important impacts, tested typically with some aspect of commitment to the product,10 with several studies pursuing further work to unpack mechanisms underlying the impacts.11

Figure 1.

Pricing and Marketing Household Financial Services in Developing Countries

A third finding from our work is that information asymmetries complicate lenders' pricing strategies. Our work in the South Africa "cash loan" market and an individual-liability microloan market in the Philippines finds evidence of substantial moral hazard.12 These papers also suggest that this problem can be addressed with stronger dynamic incentives and repayment reminders from loan officers. Another paper develops an experimental design to test for an interaction between ex-ante and ex-post asymmetric information problems - in our setting, selection on malleability to repayment incentives - and does not rule out an empirically important interaction, although the estimates are imprecise.13 That paper also tests a remedy - incentivized peer referrals - and finds evidence that referring peers are very helpful in pressuring friends to repay ex-post (thereby mitigating moral hazard). It does not find evidence that peers have additional information that lenders could use to screen or price ex-ante and thereby mitigate adverse selection.

A fourth finding is that household demand for commitment savings balances is not sensitive to price, at least within the range of market rates found in the Philippines.14 This is somewhat puzzling in light of our next set of findings - substantial price sensitivity to consumer credit interest rates - although we emphasize that whether this finding applies to other types of savings instruments and settings is an open question. A fifth finding from our work is that household demand for consumer credit is price sensitive, and sometimes in surprising ways. Our early work in this area consisted of direct-mail experiments with a small-dollar lender in South Africa.15 Potential borrowers were price sensitive, but not elastic, with respect to price cuts [0 > elasticity > -1] and were extremely elastic with respect to price increases. Direct-mail promotional experiments have the drawback of identifying short-run rather than steady-state price sensitivity; more recently, we worked with a large microlender in Mexico to randomize interest rates at the level of 80 geographical regions across the country, with experimental rates in place for 30 months.16 This design allows us to estimate elasticities over different time horizons that internalize any spillovers (e.g., information transmission) within regions. We find that loan demand is more or less unit elastic (-1) in year one, with price sensitivity increasing over time to around -3 in year three. This degree of price sensitivity is much larger than anything else found in the literature to date, with the exception of our finding on price increases in South Africa.17 We attribute this to our design's ability to capture a long-run equilibrium, as opposed, for example, to a temporary and isolated promotion.

But our most surprising finding on price sensitivity comes from a new paper on a large Turkish bank's experiment with direct-marketing of an overdraft line of credit.18 Messages mentioning the cost of overdrafting reduce overdraft usage, even though those messages offer a 50 percent rebate on overdraft interest: Substantially reducing the price of the commodity reduces demand for it. This finding is consistent with models of shrouded equilibria in which firms lack incentives to draw attention to add-on prices;19 this and other findings in the paper, discussed below, are consistent with a model of limited attention and memory.20

A sixth finding is that communications of various types can greatly affect demand. Our direct-marketing experiment in South Africa randomized mailer content alongside price and found the advertising content had large effects.21 We find some evidence that content designed to trigger automatic responses was more effective than content designed to trigger deliberative responses, but overall it was difficult to predict exactly which types of ad content would affect demand based on prior work on behavioral economics. Our experiment in Turkey varied messaging content and intensity as well as overdraft pricing, and we found evidence that both of these levers mattered greatly. In contrast to the core finding on price - that mentioning it reduces demand for overdrafts - simply mentioning overdraft availability substantially increases demand. And more intense messaging - sending the same message more often - amplifies both the demand-increasing effects of advertising overdraft availability and the demand-decreasing effects of advertising an overdraft price reduction. On the savings side, we have found, across three different banks in three different countries, that sending reminders to new commitment savings account customers increases commitment attainment.22 Messages that mention both savings goals and financial incentives are particularly effective, while other content variations such as gain versus loss framing do not have significantly different effects. This set of studies speaks to the importance of limited and malleable consumer attention to household finances.23

The findings reviewed here, taken together with the work of many other researchers, are initial steps toward unpacking the nature and implications of household demand for financial services. Our recent review articles highlight many opportunities for future work.24

Endnotes

D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Long-Run Price Elasticities of Demand for Credit: Evidence from a Countrywide Field Experiment in Mexico," NBER Working Paper 19106, June 2013; and M. Angelucci, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Win Some Lose Some? Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco," NBER Working Paper 19119, June 2013.

S. Alan, M. Cemalcılar, D. Karlan, J. Zinman, "Unshrouding Effects on Demand for a Costly Add-on: Evidence from Bank Overdrafts in Turkey," NBER Working Paper 20956, February 2015.

See D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Observing Unobservables: Identifying Information Asymmetries with a Consumer Credit Field Experiment," Econometrica, 77(6), 2009, pp. 1993-2008; G. Bryan, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Referrals: Peer Screening and Enforcement in a Consumer Credit Field Experiment," NBER Working Paper 17883, March 2012, and American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, forthcoming; and L. Beaman, D. Karlan, B. Thuysbaert, C. Udry, "Self-Selection into Credit Markets: Evidence from Agriculture in Mali," NBER Working Paper 20387, August 2014.

See D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Expanding Credit Access: Using Randomized Supply Decisions to Estimate the Impacts," Review of Financial Studies, 23(1), 2010, pp.433-64; D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Microcredit in Theory and Practice: Using Randomized Credit Scoring for Impact Evaluation," Science, 332(6035), 2011, pp.1278-84; M. Angelucci, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Microcredit Impacts: Evidence from a Randomized Microcredit Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco," NBER Working Paper 19827, January 2014, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.151-82; and A. Banerjee, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.1–21.

See O. Attanasio, B. Augsburg, R. De Haas, E. Fitzsimons, and H. Harmgart, "The Impacts of Microfinance: Evidence from Joint-Liability Lending in Mongolia," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.90-122; B. Augsburg, R. De Haas, H. Harmgart, and C. Meghir, "The Impacts of Microcredit: Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina," NBER Working Paper 18538, November 2012, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.183–203; A. Tarozzi, J. Desai, and K. Johnson, "The Impacts of Microcredit: Evidence from Ethiopia," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.54–89; E. Duflo, A. Banerjee, R. Glennerster, C. G. Kinnan, "The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation," NBER Working Paper 18950, May 2013, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.22-53; and B. Crépon, F. Devoto, E. Duflo, W. Pariente, "Estimating the Impact of Microcredit on Those Who Take It Up: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Morocco," NBER Working Paper 20144, May 2014, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 2015, pp.123-50.

See D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Price and Control Elasticities of Demand for Savings," Yale Working Paper, 2014. http://karlan.yale.edu/p/SavingsElasticities_2014_01_v9.pdf; D. Karlan, M. McConnell, S. Mullainathan, and J. Zinman, "Getting to the Top of Mind: How Reminders Increase Saving," NBER Working Paper 16205, July 2010, and Management Science, forthcoming; and N. Ashraf, D. Karlan, and W. Yin, "Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 2006, pp.635-72.

See P. Dupas and J. Robinson, "Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya," NBER Working Paper 14693, January 2009, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(1), 2013, pp.163-92; P. Dupas and J. Robinson, "Why Don't the Poor Save More? Evidence from Health Savings Experiments," NBER Working Paper 17255, July 2011, and American Economic Review, 103(4), 2013, pp.1138-71; and S. Prina, "Banking the Poor via Savings Accounts: Evidence from a Field Experiment," Journal of Development Economics, forthcoming.

For reviews of decision-making biases and other potential sources of inefficiency in markets for household debt and savings products, see D. Karlan, A. Ratan, and J. Zinman, "Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda," Review of Income and Wealth, 60(1), 2014, pp.36-78; and J. Zinman, "Consumer Credit: Too Much or Too Little (or Just Right)?" NBER Working Paper 19682, November 2013, and Journal of Legal Studies, 43(S2) (Special Issue on Benefit-Cost Analysis of Financial Regulation), 2014, pp.S209–37.

See D. Karlan, A. Ratan, and J. Zinman, "Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda," Review of Income and Wealth, 60(1), 2014, pp.36–78; and J. Jamison, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Financial Education and Access to Savings Accounts: Complements or Substitutes? Evidence from Ugandan Youth Clubs," NBER Working Paper 20135, May 2014.

See L. Beaman, D. Karlan, and B. Thuysbaert, "Saving for a (not So) Rainy Day: A Randomized Evaluation of Savings Groups in Mali," NBER Working Paper 20600, October 2014; and M. Callen, S. De Mel, C. McIntosh, C. Woodruff, "What Are the Headwaters of Formal Savings? Experimental Evidence from Sri Lanka," NBER Working Paper 20736, December 2014.

See D. Karlan and J. Zinman. "Observing Unobservables: Identifying Information Asymmetries with a Consumer Credit Field Experiment," Econometrica, 77(6), 2009, pp.1993-2008; and D. Karlan, M. Morten, and J. Zinman, "A Personal Touch: Text Messaging for Loan Repayment," NBER Working Paper 17952, March 2012.

G. Bryan, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Referrals: Peer Screening and Enforcement in a Consumer Credit Field Experiment," NBER Working Paper 17883, March 2012, and American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, forthcoming.

D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Price and Control Elasticities of Demand for Savings," Yale Working Paper, 2014. http://karlan.yale.edu/p/SavingsElasticities_2014_01_v9.pdf.

D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Credit Elasticities in Less-Developed Economies: Implications for Microfinance." The American Economic Review, 98(3), 2008, 1040-68.

D. Karlan and J. Zinman, "Long-Run Price Elasticities of Demand for Credit: Evidence from a Countrywide Field Experiment in Mexico," NBER Working Paper 19106, June 2013.

For a review of literatures on loan pricing and price sensitivity, as well as several of the other literatures referenced here, see J. Zinman, "Household Debt: Facts, Puzzles, Theories, and Policies," NBER Working Paper 20496, September 2014, and Annual Review of Economics, 7, forthcoming.

S. Alan, M. Cemalcılar, D. Karlan, and J. Zinman, "Unshrouding Effects on Demand for a Costly Add-on: Evidence from Bank Overdrafts in Turkey," NBER Working Paper 20956, February 2015.

See, e.g., X. Gabaix and D. Laibson, "Shrouded Attributes, Consumer Myopia, and Information Suppression in Competitive Markets", NBER Working Paper 11755, November 2005 and Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(2), 2006, 505-40.

P. Bordalo, N. Gennaioli, and A. Shleifer, "Memory, Attention, and Choice," Royal Holloway University of London February 2015 Working Paper, http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/evokedsets_march2_0.pdf.

M. Bertrand, D. Karlan, S. Mullainathan, E. Shafir and J. Zinman, "What's Advertising Content Worth? Evidence from a Consumer Credit Marketing Field Experiment," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(1), 2010, pp.263–305.

D. Karlan, M. McConnell, S. Mullainathan, and J. Zinman, "Getting to the Top of Mind: How Reminders Increase Saving," NBER Working Paper 16205, July 2010, and Management Science, forthcoming.

See also our work on priming (non-)effects on demand for (microcredit) microinsurance: A. Zwane, J. Zinman, E. Van Dusen, W. Pariente, C. Null, E. Miguel, M. Kremer, D. S. Karlan, R. Hornbeck, X. Giné, E. Duflo, F. Devoto, B. Crépon, and A. Banerjee, "Being Surveyed Can Change Later Behavior and Related Parameter Estimates," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(5), 2011, pp.1821–26; and V. Stango and J. Zinman, "Limited and Varying Consumer Attention: Evidence from Shocks to the Salience of Bank Overdraft Fees," NBER Working Paper 17028, May 2011, and Review of Financial Studies, 27(4), 2014, pp.990–1030.

See D. Karlan, A. Ratan, and J. Zinman, "Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda," Review of Income and Wealth, 60(1), 2014, pp.36–78; and J. Zinman, "Household Debt: Facts, Puzzles, Theories, and Policies," NBER Working Paper 20496, September 2014, and Annual Review of Economics, 7, forthcoming.