Licensing of Midwives and Maternal Mortality

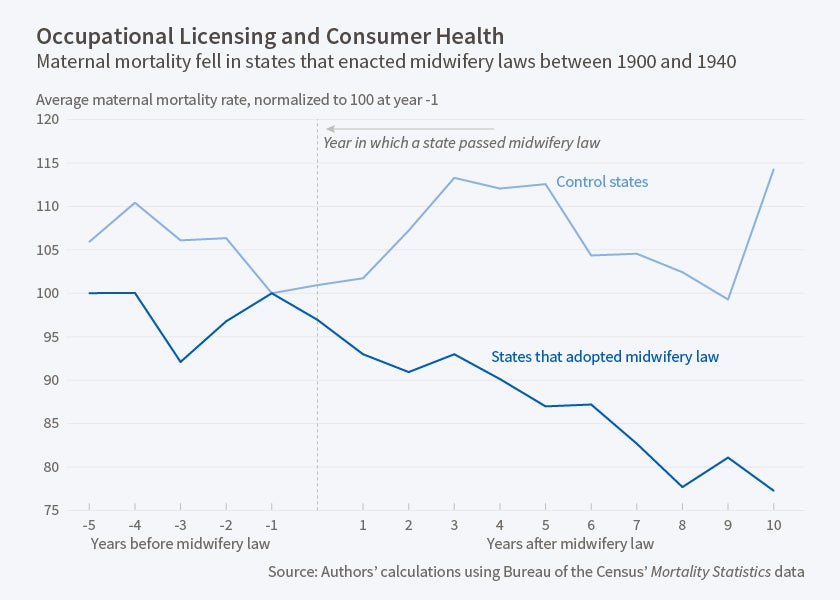

Requiring midwives to be licensed reduced maternal mortality significantly, and may have led to modest reductions in nonwhite infant mortality.

Debates over occupational licensing of workers, from real estate agents to manicurists to rehabilitation therapists, have tended to focus on the economic effects of such regulations on those getting licenses and on whether licensures increase or decrease costs for consumers.

Often overlooked is whether the ostensible purpose of licensures—to protect the health and safety of consumers—is actually achieved. In The Effect of Occupational Licensing on Consumer Welfare: Early Midwifery Laws and Maternal Mortality (NBER Working Paper 22456), D. Mark Anderson, Ryan Brown, Kerwin Kofi Charles, and Daniel I. Rees explore this issue by investigating the history of the licensing of midwives during the early 20th century. They find that the early-century movement to license midwives led to reduced maternal mortality, and, to a lesser extent, nonwhite infant mortality, suggesting that occupational licensures can indeed improve the quality of some services.

The researchers chose to study the midwifery profession because it was transformed from a largely untrained and unlicensed profession at the start of the 1900s into a largely regulated profession by 1940.

The movement toward licensing midwives began in the late 1800s in Illinois. In 1900, only eight states had some form of licensing requirements for midwives, who handled nearly half of all births in the United States. Between 1900 and 1920, 16 more states required licensing of midwives.

License requirements varied greatly from state to state. In Mississippi, license applicants were judged based on their character, cleanliness, and intelligence, but were not required to take an exam or graduate from a school. In other states, though, applicants were required to graduate from recognized schools of midwifery and to pass examinations.

Using newly digitized data originally published by the U.S. Bureau of the Census's Mortality Statistics, the researchers estimate the relationship between requiring midwives to be licensed and maternal mortality.

They find that requiring midwives to be licensed reduced maternal mortality by six percent. Licensure was associated with an almost seven percent reduction in maternal mortality caused by puerperal fever, the leading cause of maternal mortality at the time, suggesting that midwifery training in antiseptic techniques and other medical practices improved care. License requirement also led to a five percent reduction in maternal mortality from other causes, indicating that midwives had become more capable of handling other birthing complications.

In addition, the researchers found that requiring midwives to be licensed may have led to modest reductions in nonwhite infant mortality and mortality among children under the age of two from diarrhea.

The relationship between midwifery laws and maternal mortality was more pronounced in states that required applicants to pass an exam or graduate from a recognized school. The relationship between licensing and improved medical results was strongest in urban areas, which is consistent with anecdotal evidence that the enforcement of midwifery laws was less strict in rural areas and small towns.

—Jay Fitzgerald