The Power of Nudges in Exercise Commitment Contracts

Among people who have trouble sticking to an exercise regimen, a push to make a commitment appears to be effective.

Can the power of suggestion kick start an exercise habit? It depends. That's the conclusion Jay Bhattacharya, Alan M. Garber, and Jeremy D. Goldhaber-Fiebert reach in Nudges in Exercise Commitment Contracts: A Randomized Trial (NBER Working Paper No. 21406).

The researchers followed 4,000 people who enrolled in a web-based exercise commitment site. The site is designed for a self-selected group: people who recognize that on their own, they are not likely to stick to an exercise regimen. Through the web site, they enter into a "contract" to exercise. At the outset, they specify the duration of the contract in weeks, the frequency of exercise per week, and how large a financial penalty, if any, they would face for falling short of their goals.

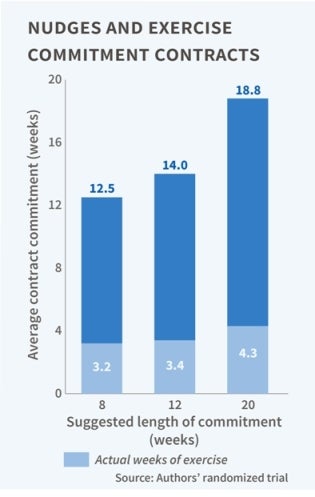

In the study, conducted between October 2010 and April 2012, the researchers examined whether people's exercise habits were affected by randomly assigning users 8-, 12-, or 20-week contract durations that would take effect by default unless the person contracting to exercise specified otherwise. The researchers found that users assigned the higher default settings tended to select longer contracts–with an 8-week default, 12.5 weeks; a 12-week default, 14 weeks; and a 20-week default, 18.8 weeks. The duration nudge had no discernible effect on users' choice of exercise frequency or penalty level.

It is important to note that these statistics are averages. Some participants selected contracts shorter than the default duration assigned to them, and some might have opted for longer contracts even if they hadn't been nudged.

Committing to a contract is one thing; fulfilling it is quite another. To determine how the nudges affected performance, the researchers performed two separate analyses.

First, they compared people on the basis of their assigned random nudge—regardless of the contract duration they actually chose. Those assigned an 8-week default completed an average of 3.2 weeks of exercise; those assigned a 20-week default completed 4.3 weeks.

Then the researchers devised a formula to tease out only those users whose contract durations appeared to have been influenced by the default assigned to them. Of that group, those who responded to the longest nudge completed 6 weeks of exercise, compared with 3.3 weeks for those who were assigned the shortest. In other words, those given the 20-week default stuck to their exercise habit for nearly twice as long as those given the 8-week default.

The researchers next set out to determine whether nudges help coax people into making a habit of exercise, which they defined as whether members of the sample group signed up for a new contract within 90 days of the expiration of the first one.

As before, the researchers first analyzed data for the entire sample group and then focused just on those users whose contracts were influenced by the nudge.

Mirroring the earlier results, those assigned the longest duration defaults were more likely to sign up again. The results were most pronounced for those successfully nudged into the longest contracts. Of that group, 9.4 percent signed new contracts within 30 days and 11.6 percent within 90 days. By comparison, only 6 percent of the entire sample signed a second contract.

The researchers point out that their sample group is not representative of the population at large. The website they studied would not attract self-disciplined people with established workout routines. Nor would it draw those–called "myopic" by the researchers–who lack the self-awareness to realize they can't on their own stick to an exercise program.

The authors point out that it is difficult to generalize from their findings to the design of exercise program incentives for the broader population. "A policy that is guaranteed to help more people than it harms... would require more information about each individual's myopia and exercise preferences than any organization typically possesses."

—Steve Maas