Cities' Bright Lights and Big Promises Dim for the Less-Educated

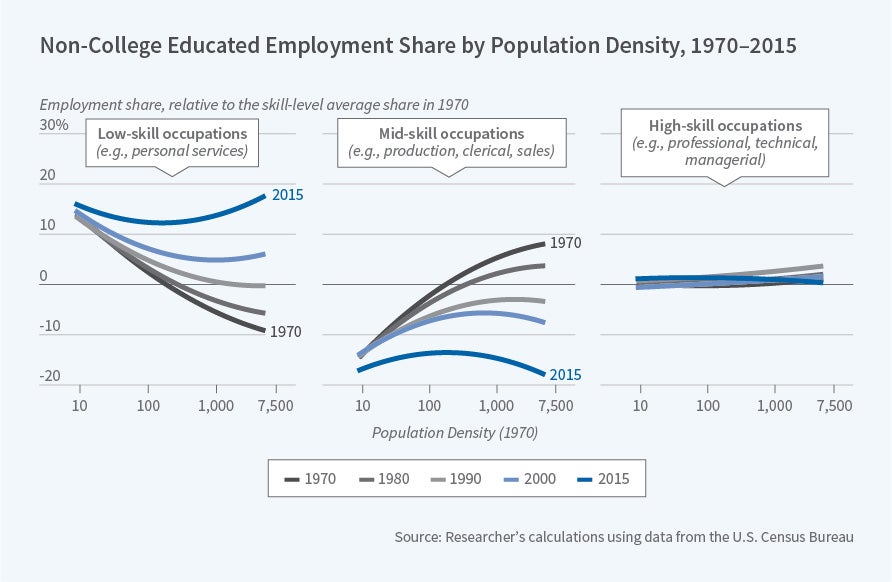

Non-college-educated workers in cities are far less likely to work in middle-skill occupations than in the past, and the urban wage premium has sharply eroded.

American cities have historically been centers of opportunity, beckoning workers from elsewhere with the promise of economic mobility.

In Work of the Past, Work of the Future (NBER Working Paper 25588), David Autor concludes that's a promise cities may no longer be able to keep. He finds that non-college-educated workers in cities are far less likely to work in middle-skill occupations than in the past. What's more, their shift into low-skilled jobs has come with a steep decline in the wage premium that urban centers once offered.

The hollowing out of middle-skill jobs has remade labor markets across the United States, leaving behind mostly low-skill, low-paid jobs on the one hand and high-skill, highly remunerated jobs on the other. Autor examines this job polarization on a geographic basis, yielding a new finding: Polarization has been far more pronounced in urban than in suburban or rural labor markets. The impact of job polarization on urban markets alone has been a key part of the secular fall in wages over the past four decades for workers without a college degree.

Autor identifies three mechanisms through which the drop in wages for non-college workers has occurred. Occupational polariza-tion has shunted non-college workers from middle-skill jobs, such as clerical or factory work, into traditionally low-paid jobs that require little specialized training, for example in the retail and hospitality sectors. Second, because occupational polarization has been much more pronounced in dense urban areas than in suburbs and rural areas, it has differentially diminished the fraction of non-college workers holding middle-skilled jobs in high-wage cities. Finally, and as a result, job polarization has unwound the wage premium for non-college workers residing in cities. This premium prevailed in the decades following World War II.

In 1970, workers without a college degree in the densest commuting zones — cities — were roughly 25 percentage points more likely to work in middle-skill occupations, and conversely, 25 percentage points less likely to work in low-skill occupations, than their non-college peers in low-density areas. (They were no more likely to work in high-skill occupations in cities than elsewhere.) Over the next 45 years, that difference eroded and ultimately reversed. By 2015, the low-skilled employment share among non-college workers was several points higher in the most versus least dense commuting zones, while the middle-skilled employment share was correspondingly several points lower.

Consider a set of common middle-skill occupations. In 1970, there was an urban-rural difference of approximately 15 percentage points in the share of workers engaged in clerical, administrative, sales, and production work. Over the next two decades, especially following the introduction of computing technologies, this share eroded. Many of these workers had been reallocated from middle-skill factory and office work to jobs in services and transportation which require fewer specialized skills.

Moving from middle-skill to low-skill jobs also depressed workers' earnings. Autor shows this by calculating how wages of college and non-college workers might have evolved if the observed polarization occurred between 1970 and 2015, but wage levels by occupation and location stayed constant at 1970 levels. Occupational reallocation on its own explains part of the fall in wages for non-college workers, but adding geography provides additional explanatory power. As an illustrative calculation, Autor finds that with the addition of a geography factor, one can proximately account for the entirety of the fall in wages of high school dropouts and high school graduates.

Now that non-college urban workers hold the same low-skill jobs their peers in rural and suburban areas do, such as custodial work, food services, protective services, recreation, health services, transportation services, and laborer occupations, the urban wage premium for non-college workers has all but vanished.

— Anna Louie Sussman