Patent Awards Stoke Startup Growth

Startups that are awarded patents in a "quasi-random" way experience faster employment and sales growth than their counterparts with unsuccessful patent applications.

Patent applications are assigned to examiners at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on a quasi-random basis. The median examiner grants a patent to 61.5 percent of the applications he or she considers, but the percentage varies substantially across examiners. This creates a "patent lottery" of sorts: an applicant who draws an examiner in the 75th percentile of willingness to grant has an 11.8 percentage-point higher probability of getting a patent than one in the same industry-year who draws an examiner in the 25th percentile. This variation in patent award probability is arguably unrelated to patent quality.

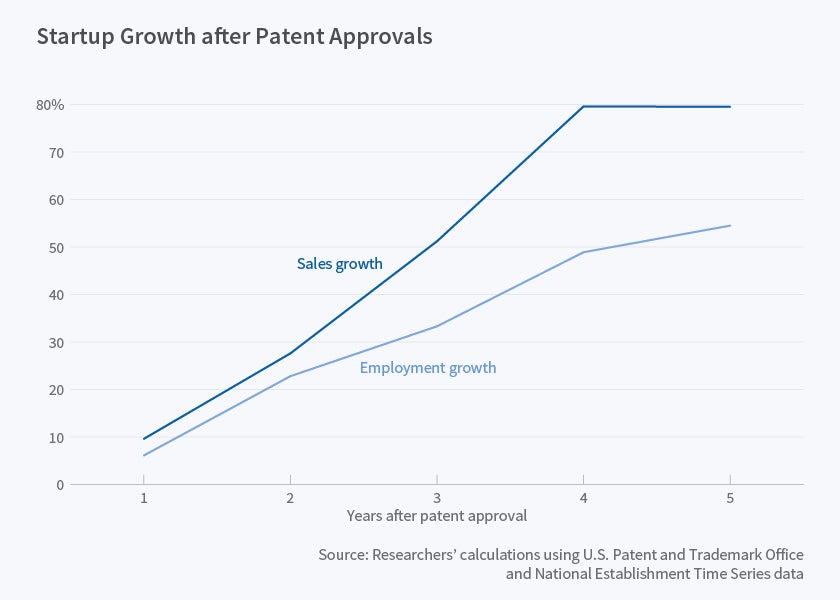

Drawing a more lenient patent examiner can make a huge difference for a startup firm, according to research reported in What Is a Patent Worth? Evidence from the U.S. Patent "Lottery" (NBER Working Paper 23268). After five years, the average employment growth of these firms is 55 percent greater, and average sales growth is 80 percent greater, than the comparable measures for firms that draw less-lenient examiners.

"A patent grant sets a startup on a growth path through funding that helps transform its ideas into products and services that generate jobs, revenues, and follow-on inventions," write researchers Joan Farre-Mensa, Deepak Hegde, and Alexander Ljungqvist. "For the average startup in our sample, these estimates imply that receiving a patent leads to 16 additional employees after five years, and $10.6 million in additional sales cumulated over five years after winning the patent lottery." The effect is particularly strong for information-technology startups.

By examining all 34,215 first-time patent applications for U.S.-based startups from 2001 through 2013, the researchers estimate a patent's private value. They compare firms that applied for patents and received them with firms that applied but did not. Previous studies have compared patent winners to firms without patents, but it is hard to establish a patent's value from this comparison because some firms without patents may have chosen other means to protect their intellectual property.

Patent lottery "winners" do not just grow faster, they are also more innovative in the years following their patent award. This is likely to be due to the fact that "winners" enjoy easier access to funding from venture capitalists, banks, and public investors. Firms that receive a first patent are awarded 42.3 percent more subsequent patents than firms whose first patent application is denied. Winning firms apply for more patents and also exhibit a higher approval rate on their applications, suggesting an increase in innovation quality. The researchers stress that their empirical methods determine "winners" through the patent lottery, not by the quality of the first patent, which avoids many potentially confounding effects.

Patents appear to serve as a kind of quality seal of approval to would-be investors. Winning the patent lottery more than doubles the likelihood that a firm is able to raise its first or second round of venture capital funding. This effect is driven by firms founded by less-experienced entrepreneurs; there is no effect for firms with experienced founders. The researchers also do not find any differences between "winners" and "losers" of the patent lottery for raising venture capital after the second round of funding.

Winning a patent appears to have a particularly large impact on firms in the IT field. IT startups tend to have young founders and products with uncertain demand and relatively high risk of imitation. Winning a patent gives would-be investors more confidence in the quality of the technology and allows the entrepreneurs to discuss their work freely without fear of having it copied. In biochemistry, in contrast, where the effect of a patent "win" is more muted, founders tend to be older, more-experienced scientists whose previous work can be more easily evaluated.

— Laurent Belsie