Declining Wealth and Work Among Male Veterans

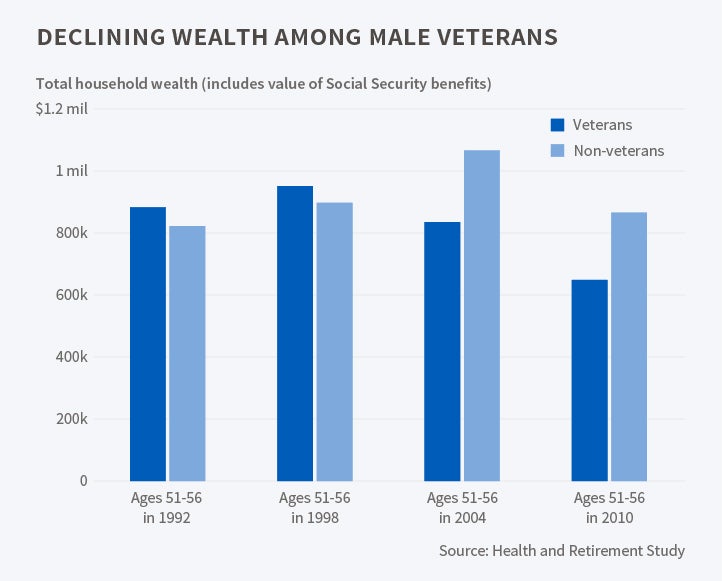

Veterans who were in their early 50s in 1992 were better educated, healthier, and wealthier than nonveterans of the same age. By 2010, this pattern had reversed.

In Declining Wealth and Work Among Male Veterans in the Health and Retirement Study (NBER Working Paper 21736), Alan L. Gustman, Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai present new evidence on how the relative financial status of veterans and nonveterans approaching traditional retirement age has varied over the last two decades. Using data on four co-horts of respondents in the Health and Retirement Study, they compare the wealth and employment status of veterans and nonveterans. Specifically, they study male veterans between the ages of 51 and 56 in 1992, 1998, 2004, and 2010. Depending on the year, one-third to one-fifth of those who served saw combat, either in Vietnam or in the First Gulf War.

The researchers find that veterans in the 1992 survey were better educated, healthier, wealthier, and more likely to be working than nonveterans of the same age. However, by 2010 the differentials were reversed in all categories. The veterans in 2010 were less well-educated, less healthy, less wealthy, and less likely to be working than nonveterans.

Did changes in military practices cause the reversal of these differentials? While the data cannot rule out this explanation, they are consistent with a simpler explanation: the incidence of military service, and the socio-economic mix of those in the armed forces, changed over time. Nearly half of the men who were in their early 50s in 1992 had served in the military. For those in this age range in 2010, only 16 percent had served. The selection mechanism was changed from a draft to an all-volunteer military in 1973, when members of the 2010 survey cohort were between 14 and 19 years old. Moreover, eight percent of the veterans in the 1992 survey cohort served for ten or more years, and 13 percent were nonwhite. The comparable statistics for the 2010 survey cohort were 13 percent and 29 percent, respectively. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that men who actively chose to join the military after the end of the draft had weaker labor-market prospects than the general population, and that this was reflected in their circumstances when they were in their early 50s.

Veterans in the oldest cohort had 14 percent more wealth when they were in their early 50s than their nonveteran counterparts. In the youngest cohort, veterans on average had 31 percent less wealth. The authors point out that these differences are in large part due to compositional changes in the veteran cohorts over time. After controlling for military experience, rank, education, race, marital status, disability status, and various measures of health, the differences in wealth between veterans and nonveterans are much smaller. For the oldest cohort they disappear, and for the youngest cohort, the disparity narrows to 13 percent.

The researchers also provide evidence on the components of wealth for veterans' households. The average total wealth of veterans' households, measured in 2010 dollars, was $883,000 for those in the oldest cohort and $648,000 for those in the youngest cohort. Almost half of this wealth came from expected Social Security payments, while pensions and real estate accounted for about 23 percent and 14 percent of total wealth, respectively. The youngest cohort had less wealth than the oldest cohort in all measured categories, with the greatest difference — $73,000 — in total pension wealth earned from all sources.

—Andrew Whitten