Tracking the Dust Bowl Migrants of the 1930s

Depopulation was due more to falling in-migration than rising out-migration; most of those who left were not farmers, and only a minority went to California.

Tragic images of the Dust Bowl's desolate farmlands and destitute migrants were ingrained into the American consciousness by John Steinbeck's classic novel The Grapes of Wrath and by the iconic photos of Dorothea Lange.

Huge swaths of the Southern Great Plains were devastated in this human and environmental disaster of the 1930s. But did events really unfold as the popular account suggests? More than 70 years later, Jason Long and Henry E. Siu develop new evidence on how many people left the Dust Bowl region, who they were, and where they went. Their findings challenge conventional wisdom.

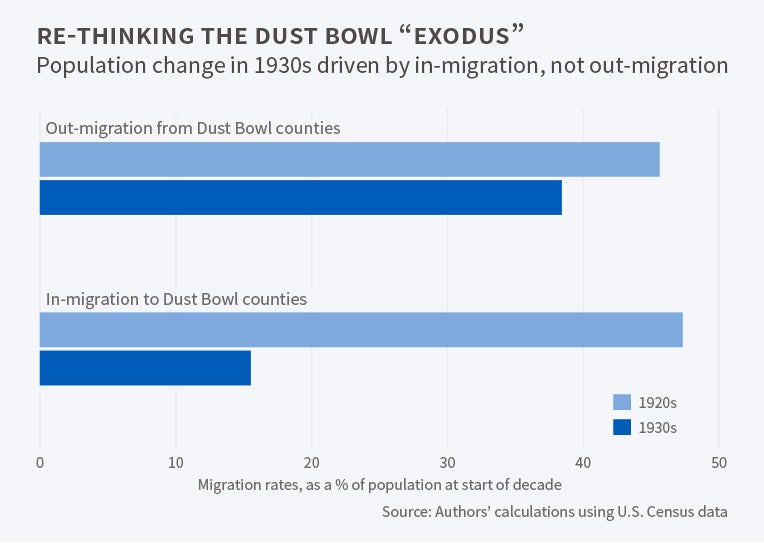

In Refugees From Dust and Shrinking Land: Tracking the Dust Bowl Migrants (NBER Working Paper 22108), they examine census data and other source materials. They find that the out-migration rate was much higher from the Dust Bowl region than from other parts of the Depression-stricken country, and farmers were the least likely to leave impacted areas. Moreover, total out-migration was only slightly higher than in the previous decade. The depopulation of Dust Bowl areas was predominantly the result of dramatically fewer people moving into the region. The researchers also find that California was the destination for only a minority of those who fled.

There is little disagreement that the Dust Bowl was the result of an almost perfect storm of environmental and economic events, starting in the early 1930s with a drought, and compounded by the enormous economic hardships caused by the Great Depression. These circumstances led to severe soil erosion, crop failures, unemployment, failed farms and businesses, foreclosures, and, ultimately, human migration.

Using longitudinal data from the U.S. Census and other sources such as Ancestry.com, the researcher focus on individuals living in the 20 hardest-hit counties in four states: Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. They analyze data from 1920 through 1930, before the Dust Bowl, and 1930 through 1940, during the dramatic events.

They find a population decline of 19.2 percent, from 120,859 people to 97,606 people, in the Dust Bowl counties studied, compared to a 4.8 percent increase in population in other parts of the four states during the same period. However, they also discover that the 20 counties had undergone tremendous migration "churn" in the years immediately after World War I, experiencing an in-migration rate of 47.3 percent in the 1920s, as the area boomed. In-migration fell to only 15.5 percent in the 1930s. The researchers conclude that depopulation was largely the result of falling numbers of new residents moving to these counties and "was not due to an extraordinary exodus relative to historical norms."

They also find that farmers—so closely associated with the Dust Bowl tragedy in literature and films—were actually the least likely to move from the area. Instead, they tended to remain and to retain their assets and properties while others fled.

Where did migrants go? The majority of those who left the 20 study counties stayed in the four states covered by the study, while about 37.1 percent left. Contrary to the enduring image of "Okies" fleeing en masse to California, the research finds that migrants from the Dust Bowl region were no more likely to move to California than migrants from other parts of the U.S., or those from the same region ten years prior. "In this sense, the westward push from the Dust Bowl to California was unexceptional," the researchers report.

—Jay Fitzgerald