Cost Pass-through Rule Reduces Incentive to Stop Methane Leaks

Regulations allow natural gas distribution companies to pass the cost of leaked gas to retail consumers, with safety and climate consequences.

Methane, the primary component of natural gas, is a greenhouse gas with 34 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. It is estimated that more than one percent of methane in the U.S. supply chain escapes into the atmosphere, and that 20 percent of this leakage occurs from degraded pipes and loose-fitting components during distribution of natural gas to homes and businesses.

In Price Regulation and Environmental Externalities: Evidence from Methane Leaks (NBER Working Paper 22261), Catherine Hausman and Lucija Muehlenbachs show that current regulatory structures weaken the incentives for gas distribution firms to find and fix these leaks.

Because natural gas distribution requires extensive infrastructure investment, it is a natural monopoly that is regulated to ensure that customers can purchase the gas at a fair price while providing utility investors with adequate returns. Regulations negotiated by local public utility commissions usually permit distribution companies to pass on the cost of leaked gas to retail customers. This means that the distribution companies have less incentive to fix leaks than they would if they had to bear the lost-gas costs themselves.

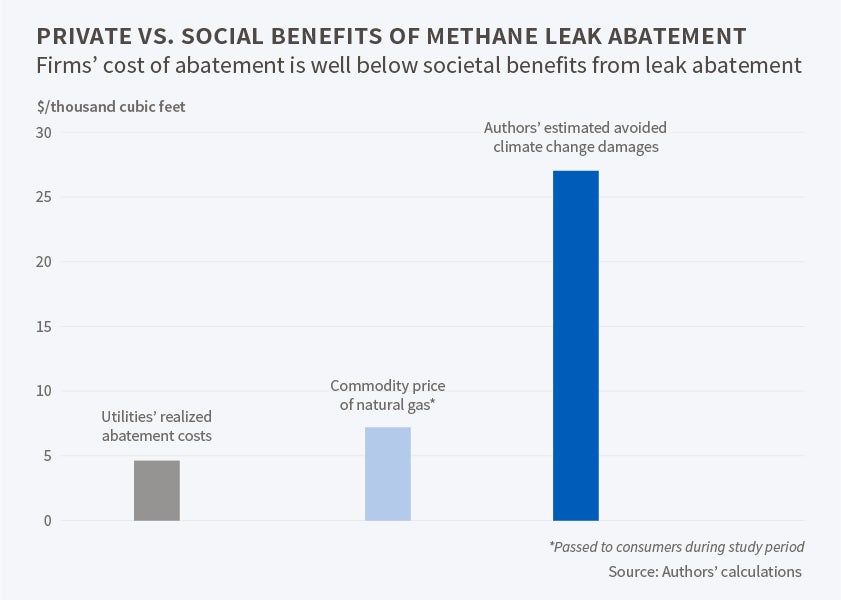

The researchers estimate that the social cost of methane leaks is far higher than the commodity value of the lost gas. Accumulated leaked methane can explode, causing human deaths and property damage, and methane's contribution to climate change far exceeds the life and property losses. In 2015, the climate-change impact of the gas leaked in the U.S. from wellhead to end-user was estimated at more than $8 billion.

Drawing upon data from several government agencies on the operations of 1,500 natural gas companies from 1995 to 2013, the researchers estimate the cost of abatement activities undertaken by utilities and find that, although natural gas distribution companies do repair leaks, the amount they spend on leak detection and repair is substantially below the value of the leaked gas.

In recent years, new safety regulations have required utilities to work more actively to detect and fix leaks. The researchers find that new standards from the U.S. Department of Transportation's Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration that took effect in August 2011, and regulations issued by the California Public Utilities Commission after a 2010 gas explosion in San Bruno, California, have led to leak repairs around the country—with economic and climate benefits on top of the safety benefits the regulations were intended to realize. The authors conclude that repairs could be made that would yield more savings in unleaked gas than the cost of the repairs themselves.

—Deborah Kreuze