The Number of High-Growth, Job-Creating Young Firms is Declining

Since 2000, both the number of start-up firms and the number of these firms that display very rapid growth has been declining.

The number of start-up firms in the United States has been declining in recent decades. Prior to 2000, the employment effects of this decline were partly offset by the presence of a small number of high-growth young companies. That pattern seems to have changed.

In Where Has All the Skewness Gone? The Decline in High-Growth (Young) Firms in the U.S. (NBER Working Paper 21776), Ryan A. Decker, John Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda show that the general decline in new firms has been accompanied, since around 2000, by a corresponding decline in the number of high-growth start-ups.

New firms accounted for about 13 percent of all companies in the late 1980s, but only about eight percent two decades later. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, a small number of young, innovative, and dynamic companies grew at very high rates. This "skewness" in the rate of job creation among young firms increased the contribution of young firms to overall job creation.

The researchers measured skewness patterns and other business trends within industries, from manufacturers to mom-and-pop retailers to technology start-up firms. Relying largely on statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau's Longitudinal Business Database (LBD) for the years 1976 through 2011, they analyzed information on firm growth rates by detailed industry, firm age, and firm size.

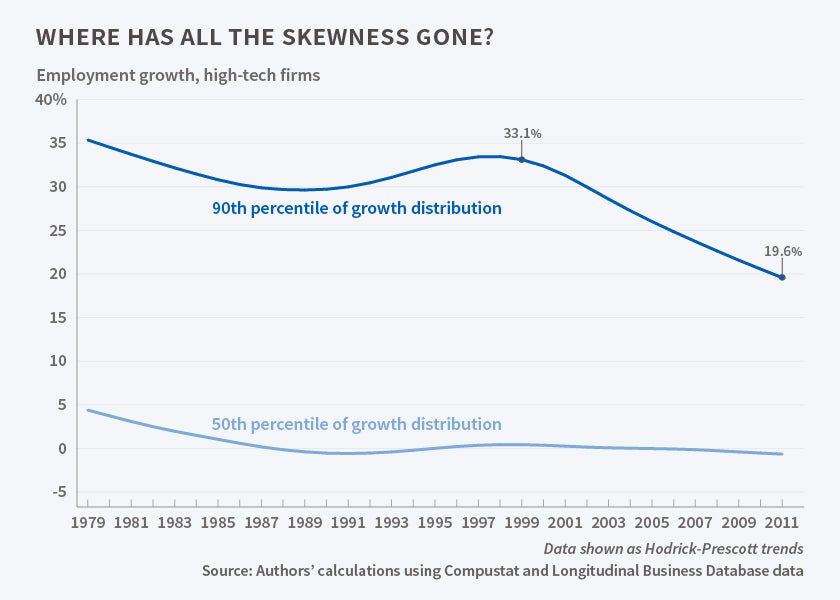

The researchers found positive job growth skewness within some industries in the early years that they analyzed, particularly in the services and high-tech sectors of the 1980s and 1990s. As late as 1999, a firm at the 90th percentile of the employment growth rate distribution grew 31 percent faster than the median firm. In addition, the jobs-growth differential between firms at the 90th and 50th percentiles was 16 percent larger than that between firms at the 50th and 10th percentiles, again suggesting positive skewness in employment growth rates. But the employment-growth distribution changed substantially in the post-2000 period. By 2007, the 90-50 differential was only 4 percent larger than the 50-10, and it continued to decline throughout the period analyzed.

These trends suggest that startups contributed less to U.S. job creation in the post-2000 period than they did in earlier decades, but the researchers cannot yet explain the dynamic. "While we have attempted to describe in detail several aspects of declining skewness in the U.S. using industry, size, and age comparisons," they write, "we have not identified the underlying causes of these trends." Among potential explanations are credit constraints, rising investments in equipment that reduce the need for new employees, outsourcing of work to developing countries, and larger companies acquiring younger firms at an earlier stage of development.

The researchers note that the Great Recession had a negative effect on employment growth, but they point out that the decline in the number of high-growth young firms started well before that downturn.

"Historically, the U.S. has exhibited a high pace of entrepreneurship with a small share of fast growing young firms disproportionately accounting for job creation and productivity growth," they conclude. "The decline in startups and the accompanying decline in high growth young firms either suggests adverse consequences for U.S. economic growth or a change in the way that such growth will be achieved."

—Jay Fitzgerald