Effects of Mortality on Fertility after 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami

In communities with high mortality, both women who lost children and women who were childless were more likely to have children.

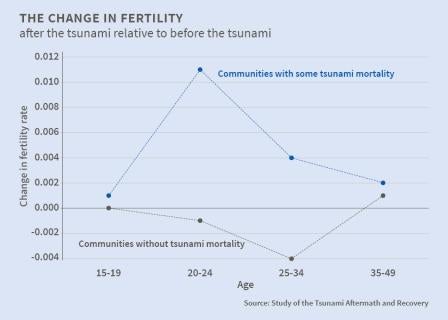

Natural disasters that increase child mortality also may cause aggregate fertility rates to rise. In The Effects of Mortality on Fertility: Population Dynamics after a Natural Disaster (NBER Working Paper No. 20448), Jenna Nobles, Elizabeth Frankenberg, and Duncan Thomas find a significant increase in aggregate fertility in their study area during the four years after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, as indicated by a 0.7 increase in the total fertility rate over the expected rate. They find that mothers who lost one or more children were significantly more likely to bear additional children after the tsunami, but this additional fertility accounted for just 13 percent of the aggregate fertility increase. The majority of the aggregate increase occurred because childless women in communities with high mortality rates were more likely to begin childbearing than childless women in other communities.

The December 26, 2004, Sumatra-Andaman Islands earthquake was one of the largest ever recorded. Three tsunamis with waves 50 to 100 feet tall came ashore in the Indonesian provinces of Aceh and North Sumatra, killing an estimated 170,000 people. Differences in coastal topography protected some communities even as neighboring communities experienced mortality rates of over 50 percent.

In early 2004, Statistics Indonesia conducted an annual, nationally representative socio-economic survey known as SUSENAS, which provided baseline data for the Study of the Tsunami Aftermath and Recovery (STAR), an international collaborative project of Indonesian and U.S. investigators led by Frankenberg and Thomas. The STAR team reinterviewed individual SUSENAS respondents in tsunami-affected areas, determined mortality status for 97.4 percent of the SUSENAS sample, and developed estimates of local community damage using satellite photos cross-validated by interviews with local authorities.

The authors analyzed the fertility of individual women in STAR in the pre-tsunami baseline survey and in five annual post-tsunami surveys. These surveys provided detailed information about the mortality of household members. Researchers were able to contact 95 percent of those who survived the tsunami, obtaining complete pregnancy histories from women of reproductive age. Individual response to losing at least one child was estimated using pre-tsunami data on age, number of children, education, per capita household expenditure, and home and land ownership. Individual experiences during the disaster were controlled for, using a variable recording whether a person had seen friends or family struggle or disappear in the water. Of the 2,301 women who were mothers at the time of the tsunami, just over 5 percent lost a child.

Mothers who lost a child were 37 percent more likely to have another child by 2009 regardless of the child's age. In communities where no one was killed, women without children before the tsunami were less likely to have a child in 2006-09. In communities with high mortality, both women who had lost children and women who had not had any children before the tsunami were more likely to have children. As a result, an estimated 9,500 additional children were born by the end of 2009 in study-area communities that experienced substantial tsunami mortality. The authors note that although a five-year, post-disaster follow-up allows them to assess the effect of the tsunami losses on older women, it is too early to tell whether the increase in fertility reflects a shift in fertility timing or will result in larger complete family sizes.

-- Linda Gorman