Health Capacity to Work at Older Ages: Evidence from the US

Health status at older ages has improved, not worsened; labor force participation has not kept pace.

Raising the eligibility ages for benefits is sometimes advanced as a possible response to the rising cost of Social Security and Medicare that will be associated with the aging of the U.S. population in coming decades. By raising the age at which pension and health benefits could be claimed, these changes would make it more costly for older individuals to leave the labor force. A central issue in evaluating such proposals is whether older Americans have the health capacity to work longer than they currently do.

In Health Capacity to Work at Older Ages: Evidence from the U.S. (NBER Working Paper 21940), Courtney Coile, Kevin S. Milligan, and David A. Wise find that many of today's workers are healthy enough to extend their working lives. The study employs several yardsticks to measure health capacity in the retirement-age population.

The researchers first compare the employment of older men today to that of men in the past with the same level of health, measured using mortality risk. In 1977, a 49-year-old man had a 0.8 percent chance of dying within a year and 89 percent of 49-year-old men were participating in the workforce. By 2010, the age at which the male mortality rate was 0.8 percent had risen to 55, but 55-year-olds' labor force participation rate was just 72 percent. If men in 2010 had exhibited the same labor force participation rates as their 1977 predecessors who faced the same mortality rates, i.e., if 55-year-old men in 2010 had participated as much as 49-year-old men in 1977 and so on for men of other ages, then on average men would have worked an additional 4.2 years between the ages of 55 and 69. The researchers note that their findings are somewhat sensitive to their choice of base year. If instead of comparing 2010 to 1977 they compared it with 1995, a low point in postwar labor force participation, they estimate that a 2010 worker would spend just 1.8 additional years in the workforce.

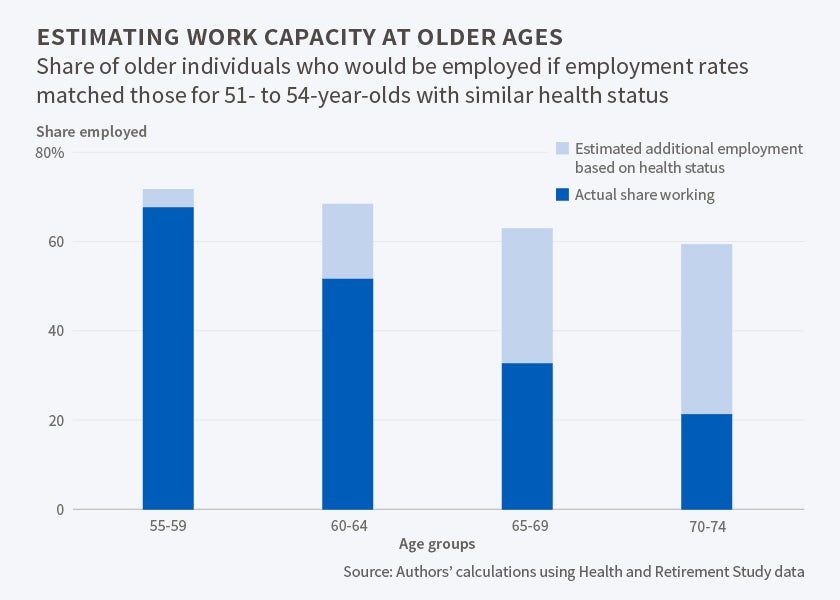

The researchers also compare older individuals to slightly younger workers with similar health, measured using self-reported health conditions, disabilities, and medical care usage. They estimate that if older men had the same labor force participation rates as younger men who exhibited the same health status, then the labor force participation rate among 60 to 64 year olds would be 17 percentage points greater than it was, and that the analogous rate for those 65 to 69 would be 31 percentage points higher. They estimate that the average number of years worked between the ages of 55 and 69, which was 7.9 in 2010, would have been 2.6 years greater.

The researchers found that improvements in self-assessed health were disproportionately greater among the highly educated, suggesting that they could be in a better position to extend their work lives than their contemporaries with less education.

The researchers note that their study does not consider other factors that may affect workforce participation, such as age discrimination and business cycle fluctuations. They also note that while the older population in general is healthier than in the past, there are still some who may find it difficult to work and whose primary source of support is likely to be government transfer programs. They emphasize that their "estimates should not be taken as a reflection of how much older workers 'should' work." Increasing people's years at work "may not be a socially desirable outcome," they point out, "since leisure time has value as well."

—Steve Maas