Declining Fertility in Wealthy Nations

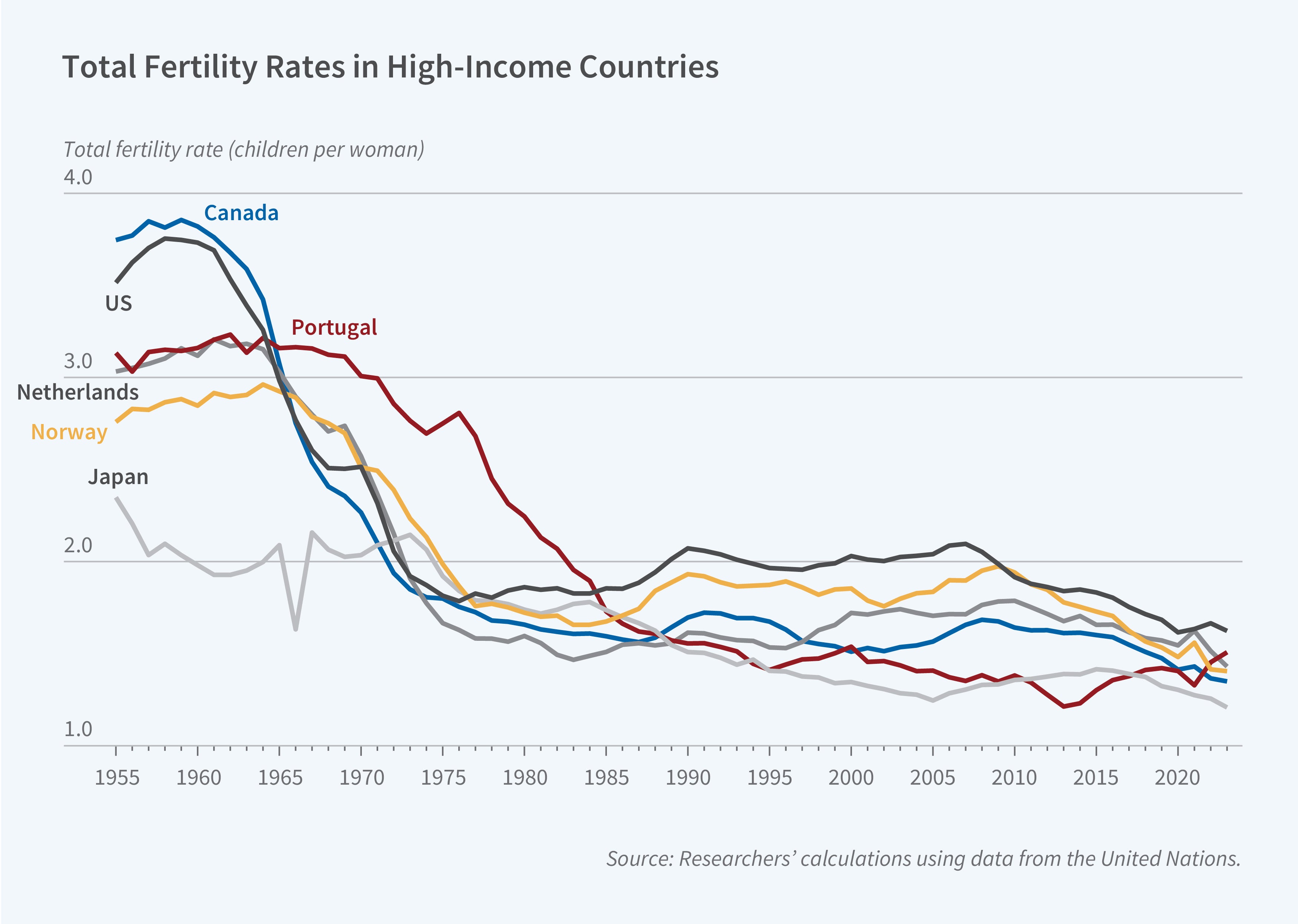

Birth rates have fallen to historically low levels across high-income countries, with many nations now well below the 2.1 total fertility rate needed to maintain population size. This demographic shift has raised concerns about workforce shrinkage, economic stagnation, and the sustainability of social insurance programs.

In Why Is Fertility So Low in High Income Countries? (NBER Working Paper 33989), researchers Melissa Schettini Kearney and Phillip B. Levine document these trends across several countries and explore the reasons for the decline. Using cohort-level data on fertility, they track childbearing patterns across cohorts of women born after 1970 to provide descriptive insight into the nature of recent declines. They document a clear pattern of rising childlessness; in all countries studied, the share of women remaining childless by age 30 has increased to close to 50 percent or more for the youngest cohorts. The documented patterns suggest that recent cohorts of women in countries including the United States, Canada, Japan, and Norway are likely on track to have higher rates of childlessness and lower completed fertility than women who were born in the 1970s and 1980s.

Falling birth rates in high-income countries are not well explained by traditional economic models but likely reflect a fundamental reordering of adult priorities shaped by social and cultural forces.

The researchers review the evidence on potential explanations for the recent decline in fertility and find that traditional economic explanations cannot account for much of it. They report that small financial incentives or incremental family-friendly policies may increase births modestly, but these relationships cannot explain recent trends. The financial and time trade-offs between parenthood and career advancement are of fundamental importance to working parents and would-be parents in modern economies, but policies that incrementally affect the ability to combine market work and parenthood have at best a small effect on fertility outcomes. Causal studies find that at a micro level, increases in income lead to increases in fertility, but this relationship also cannot explain the widespread decline in fertility in high-income countries in recent decades.

The researchers conclude that a broader perspective is needed to capture the complexity of the modern fertility landscape. They conclude that the recent decline in fertility likely reflects "shifting priorities"—or a reordering of adult priorities where parenthood plays a diminished role in life planning—and that these shifts are likely shaped by broad cultural, normative, and structural shifts, such as the increased intensity of parenting, peer effects, media influences, and declining religious observance. The researchers emphasize the need for consideration of and additional research into the role of factors other than opportunity costs, prices, and income that are typically the focus of economic studies of fertility determination.