Parental Divorce and Children's Long-Term Outcomes

Nearly one-third of American children experience parental divorce before reaching adulthood, making family dissolution a significant factor in child development. In Divorce, Family Arrangements, and Children’s Adult Outcomes (NBER Working Paper 33776), Andrew C. Johnston, Maggie R. Jones, and Nolan G. Pope provide new quantitative evidence on the association between adult outcomes and the presence or absence of a divorce during childhood. They analyze over 5 million children born between 1988 and 1993. They link tax records, Census Bureau data, and Social Security Administration files to build a dataset with information on family structure changes and long-term outcomes through 2018, when the study population was between 25 and 30 years old.

Children whose parents divorce experience reduced adult earnings and higher rates of teen pregnancy and incarceration.

The researchers find that divorce is associated with substantial and immediate changes in children’s wellbeing. Teen birth rates increase by 63 percent above pre-divorce levels, rising from 8 to 13 births per 1,000 girls annually in the years following divorce. Child mortality increases by 35 to 55 percent after divorce relative to a baseline of 27 deaths per 100,000 children annually and persists at elevated levels for at least 10 years.

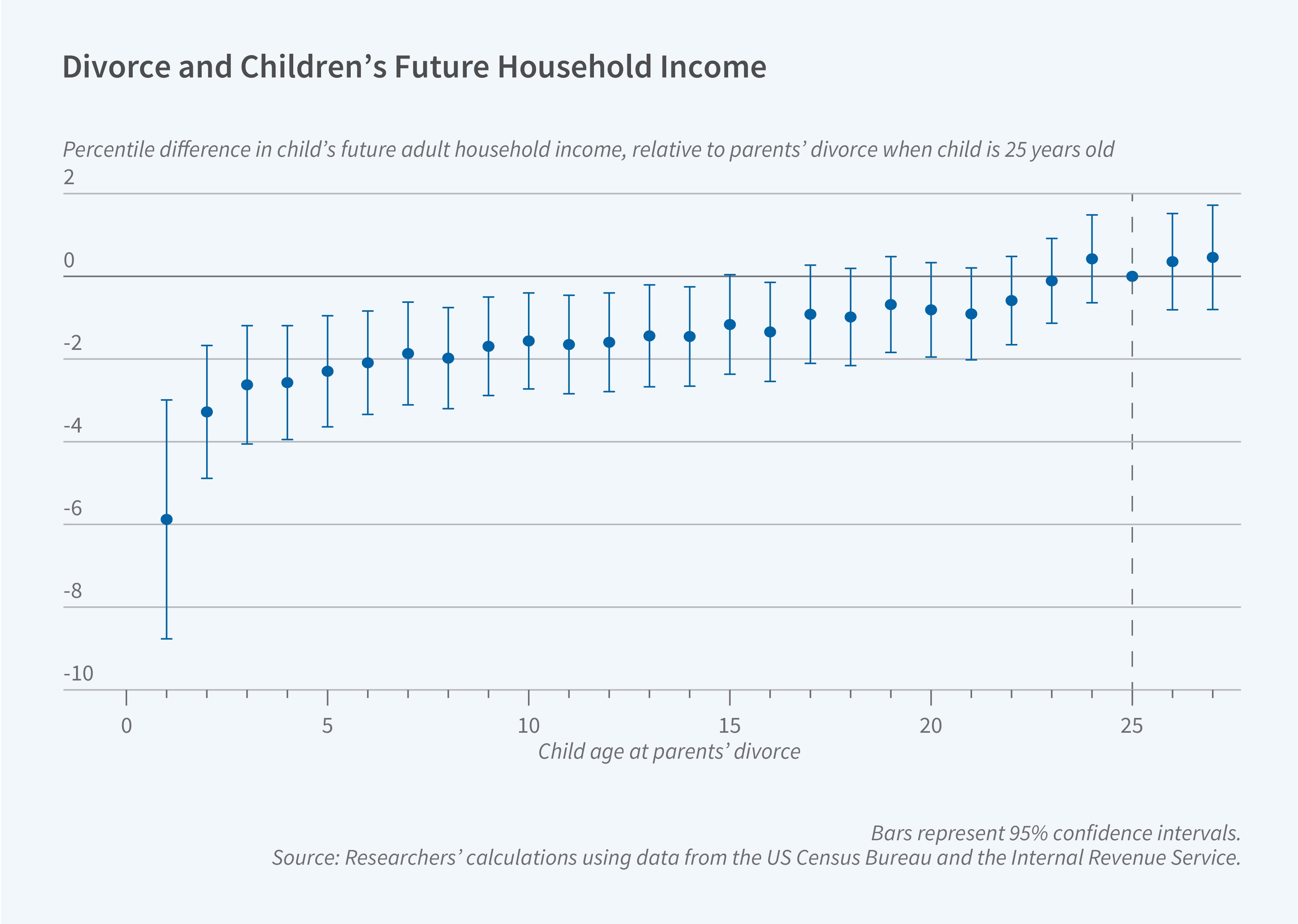

Over the long term, children experiencing divorce during early childhood (ages 0–5) show reduced adult earnings. At age 25 they rank, on average, 2.4 percentile points lower in the income distribution than children who did not experience a divorce. By age 27, this effect rises to 3.9 percentile points. This translates to approximately 9 to 13 percent lower earnings, comparable to losing one year of education or living in a neighborhood of 1 standard deviation lower quality throughout childhood. Early childhood divorce is associated with a 0.9 percentage point higher probability of teen birth, a 73 percent increase relative to the baseline. It is also associated with a 0.39 percentage point (35 percent) increase in mortality by age 25 and a 0.2 percentage point (43 percent) higher probability of incarceration. Children of early divorce are also substantially less likely to live on college campuses in their late teens and early twenties, with college residency declining by approximately 4 percentage points (over 40 percent relative to the baseline rate). The effects vary by timing, with divorce during early childhood associated with the largest impacts across most outcomes. The effects are broadly similar across income levels, racial groups, and gender.

The researchers use estimates from earlier studies of outcomes for young adults to provide estimates of the relative importance of three potential channels through which divorce could matter. First, they estimate that changes in household resources account for between 10 and 44 percent of the correlation between divorce and adult earnings. Second, they conclude that deterioration in neighborhood quality could explain an additional 16 percent of divorce’s impact on income at age 25. The divorce-related decline in neighborhood quality could reduce children’s income by 0.42 percentile points, compared to the total divorce effect of 2.44 percentile points. Neighborhood changes could account for 17 percent of teen birth effects and 29 percent of incarceration effects. Finally, an increase in physical distance between children and nonresident parents could account for 15 percent of the mortality effects and 22 percent of the teen birth effects, likely reflecting reduced parental supervision and involvement. Together, these three mechanisms could explain 25 to 60 percent of divorce’s total effects on children’s outcomes, suggesting that other unmeasured factors—such as changes in family dynamics, parental time investment, and emotional stability—also play important roles.

The researchers are grateful for financial support from the Smith Richardson Foundation.