The Impact of Evictions on Children

Concern about children’s welfare is often cited as a reason for strong tenant protection laws. In The Effects of Eviction on Children (NBER Working Paper 33659), Robert Collinson, Deniz Dutz, John Eric Humphries, Nicholas S. Mader, Daniel Tannenbaum, and Winnie van Dijk provide new evidence on the causal impact of evictions on various measures of children’s welfare.

Using data from Chicago and New York City, the researchers compare children of families who were randomly assigned a stricter judge in eviction court to children whose families were randomly assigned a more lenient judge to study the causal impacts of eviction on children. Children in evicted families are more likely to experience homelessness the following year (7 percentage points more likely in Chicago and 3.1 percentage points more likely in New York, relative to rates for non-evicted children of 0.9 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively). Eviction also leads to longer-term housing instability, with more moves in the next two years.

In Chicago, eviction increases the probability that a child will live in a multigenerational household by 13.2 percentage points. Similarly, children in evicted families are 16.9 percentage points more likely to live in a “doubled-up” household—one with more adults than just their parents—in the following year. Eviction does not reduce the likelihood that a child lives with their parents or in a higher-poverty neighborhood than before eviction, or that the child moves to a different school district.

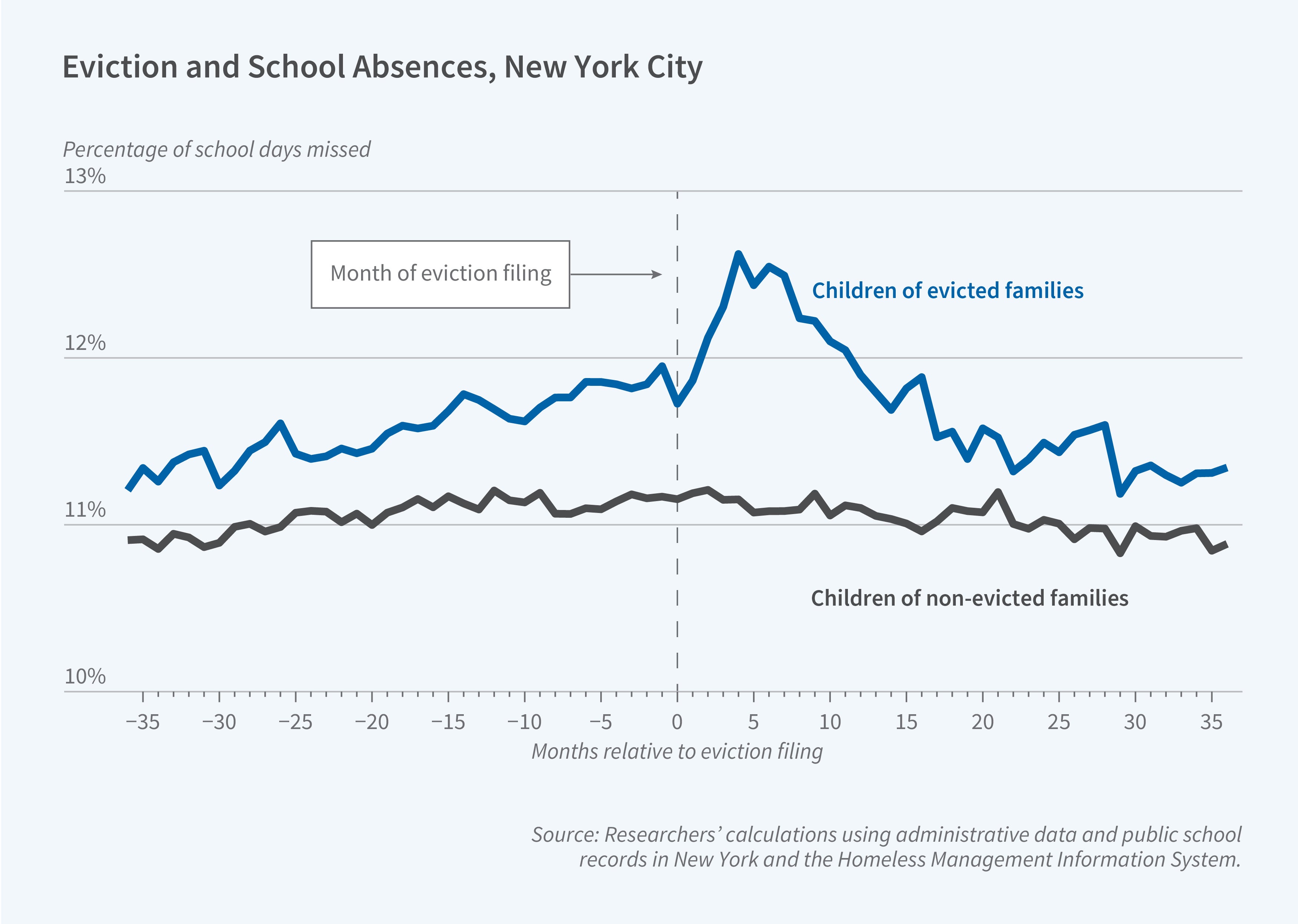

Evicted children are more likely to be chronically absent from school, with eviction increasing absence rates by 2.4 percentage points or about 4.3 school days during a typical year. Eviction raises the likelihood of chronic absenteeism by 9 percentage points, a 21 percent increase over that for non-evicted peers.

Evicted children are 5.3 percentage points more likely to repeat at least one grade of school by the second year after the eviction filing. While evicted children do not have lower standardized test scores, they are more likely to miss tests, consistent with their higher absenteeism rates.

Additionally, eviction reduces high school credits completed by 14.4 percentage points in the first year after eviction and the likelihood of finishing high school. Students in families that have been evicted are 12.5 percentage points less likely to graduate than their non-evicted peers in households that faced eviction proceedings. The graduation rate for students in the latter group of households is 68 percent. These effects are particularly negative for boys.

The researchers document substantial selection into eviction court, regardless of the eventual outcome. Children in families facing eviction cases were more likely to be chronically absent and more likely to have low scores in math and reading than the general public-school population in the year before their case was filed. Similarly, children in evicted households were more likely to be absent in the year before eviction than their peers from households that faced a threat of eviction but were not evicted. These patterns underscore the importance of the researchers’ approach of using the decisions of randomly assigned judges to measure causal impacts.

— Greta Gaffin

The researchers gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation (SES-1757112, SES-1757186, SES-1757187), the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Spencer Foundation, the Kreisman Initiative for Housing Law and Policy, the Horowitz Foundation for Social Policy, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, and the Yale Tobin Center for Economic Policy.