Long-Term Impacts of Residential Racial Desegregation Programs

Growing up in racially and economically segregated neighborhoods can have long-lasting effects. In 1966, Black families in Chicago sued the public housing authority over housing policies that segregated Black families. In response, the Chicago Housing Authority created a voucher program that would assist these families in moving to middle-income neighborhoods. Initially, families were relocated to predominantly White neighborhoods. After experiencing difficulty finding enough White neighborhoods willing to accept Black residents, program administrators began to relocate families to revitalizing Black neighborhoods as well.

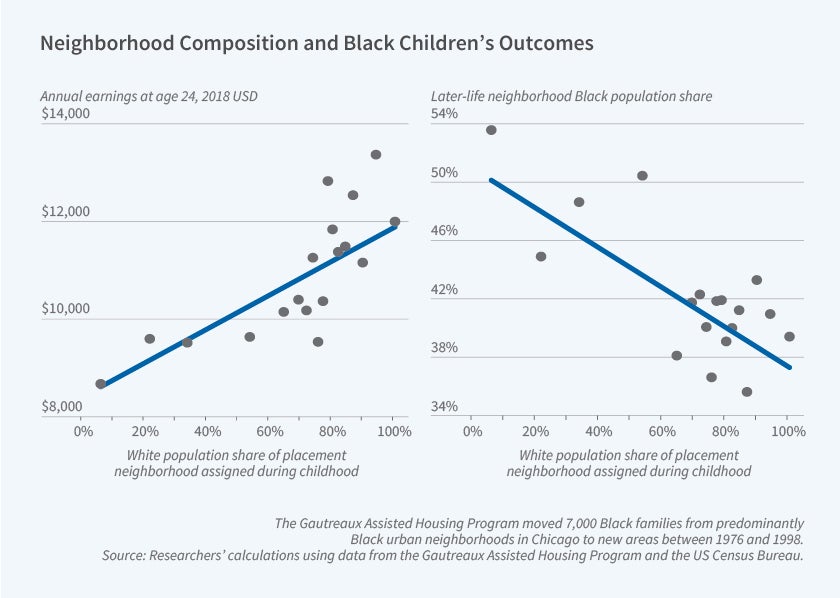

In The Long-Run Effects of America’s Largest Residential Racial Desegregation Program: Gautreaux (NBER Working Paper 33427), Eric Chyn, Robert Collinson, and Danielle H. Sandler compare the long-term outcomes of children who moved to predominantly White neighborhoods to those of children who moved to revitalizing Black neighborhoods. The authors find that children who relocated to predominantly White neighborhoods (“treated” children) had significantly higher adult earnings than those who moved to Black neighborhoods. They earned $16,910 more by age 28, $24,980 more by age 33, and $34,090 more by age 38.

Black children who were relocated from housing projects to predominantly White neighborhoods grew up to have substantially more wealth, were more likely to marry, and were more likely to live in diverse neighborhoods than their peers who were moved to predominantly Black neighborhoods.

This effect was greater for younger children, implying that their longer exposure to majority White and middle-class neighborhoods was important. Benefits of relocation to a predominantly White neighborhood shrink by between $338 and $473 per year of reduced exposure.

As adults, those who had moved to White neighborhoods as children were also more likely to be homeowners, married, and to live in neighborhoods with lower poverty rates. The authors’ results also suggest that male children were 38 percent less likely to have died by 2019.

The program initially looked to place families in areas that were no more than 30 percent Black, which was a significant change from the highly segregated places where they had been living previously. This created lasting social effects: Children who moved to White neighborhoods were 2.1 percentage points more likely to marry a White partner in adulthood.

The authors find that while the children who moved to predominantly White neighborhoods in connection with this program experienced positive long-term effects, their parents experienced at most modest effects. While parents were more likely to live in racially diverse areas, their earnings were not significantly higher than those of parents who moved to predominantly Black neighborhoods.

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation, NSF Award Number 2018266.