The Lifetime Medical Spending of Retirees

Older households in the U.S. face the risk of catastrophic medical expenditures during retirement. While Medicare covers some hospital expenses starting at age 65, as well as doctor's visits and prescription drugs for beneficiaries who sign up and pay for Part B and Part D coverage, there remain substantial uncovered costs. For example, Medicare does not cover long hospital or nursing home stays and requires copayments for many medical goods and services. Medicaid provides coverage of long-term care expenses for the poor, but families with significant assets are not eligible (unless they first expend most of their wealth).

Understanding the level and risk of medical spending on retirees is important for households seeking to save adequately for retirement and manage the decumulation of their retirement savings, as well as for policy makers interested in retirement security.

In The Lifetime Medical Spending of Retirees, (NBER Working Paper No. 24599), researchers John Bailey Jones, Mariacristina De Nardi, Eric French, Rory McGee, and Justin Kirschner estimate the distribution of lifetime medical spending for retired households with a head age 70 or above. Their estimates include out-of-pocket spending as well as Medicaid expenditures, as this represents the risk that wealthier households face, as well as the medical spending risk less wealthy households would face were Medicaid not available.

The researchers make use of data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), focusing on households age 70 and above at the first interview, who are followed for up to 20 years. The HRS provides information on all out-of-pocket medical spending. These data are supplemented with information on Medicaid spending from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, using characteristics available in the two data sets to estimate Medicaid spending for HRS respondents.

The researchers use these data to estimate the probability that individuals transition over time between being in good health, in poor health, in a nursing home, and deceased, based on the individual's current health status and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. They also estimate models relating the mean and variance of medical spending to health status and these other factors. Results from the two models are combined to predict how health and medical spending will evolve with age for each household.

Focusing first on annual household spending, the researchers find that this measure rises rapidly with age, with mean out-of-pocket and Medicaid expenditures of $5,100 at age 70, rising to $29,700 at age 100. At the 95th percentile, annual expenditures are $13,400 at age 70 and $111,200 at age 100.

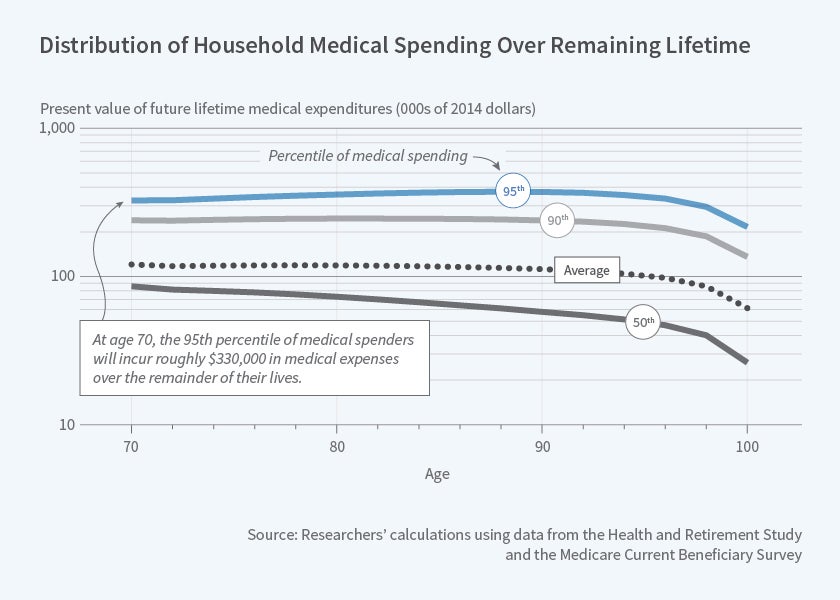

Spending at each age can be aggregated to create an estimate of lifetime medical spending. At age 70 and each age thereafter, the researchers calculate the present discounted value of remaining medical expenditures from that age forward. The resulting values can be considerable. Households who turned 70 in 1992 will on average incur over $122,000 in out-of-pocket and Medicaid spending over the remainder of their lifetime. The top 5 percent of spenders will incur expenditures of over $330,000. This value does not fall with age, as might be expected — older households have fewer remaining years of life but higher annual expenditures, and the latter drives remaining medical spending to continue rising until about age 90.

The researchers uncover a number of other interesting patterns in lifetime medical spending. Women have higher spending than men, as might be expected due to their longer life expectancy. Perhaps more surprisingly, those who are initially in good health have higher spending than those in poor health, since the former tend to live longer and medical expenditures rise with age. An important caveat to this is that individuals who are initially in nursing homes have the highest expenditures, despite having high mortality, due to the high cost of nursing home care. High-income households have higher lifetime expenditures due both to their longer life expectancy and their tendency to spend more at each age. Only 40 percent of the variation in medical expenditures can be explained by factors such as income and health status, indicating that much of the variation in spending is due to idiosyncratic health shocks.

The share of medical expenditures that is covered by Medicaid is highly relevant for retirement planning. This share varies considerably by the household's permanent income level. At the bottom of the income distribution, mean lifetime out-of-pocket expenditures as of age 70 are about 43 percent of mean combined (out-of-pocket and Medicaid) expenditures, implying that Medicaid covers about 57 percent of the total. By contrast, at the top of the income distribution, Medicaid covers 21 percent of lifetime expenditures as of age 70 and 30 percent as of age 100. These figures reflect the fact that, on the one hand, most high-income households do not receive Medicaid; however, those that do have had their assets exhausted by high medical expenses, leading to large Medicaid benefits. At every income level and age, households with higher combined expenditures have a larger share of their expenditures covered by Medicaid.

In concluding, the researchers note that the level and dispersion of medical spending is high and diminishes only slowly with age. While some fraction of medical spending is predictable, a large share is due to unanticipated health shocks. Medicaid covers the majority of health costs for the poor and reduces their risk of medical expenditures; to a lesser extent, it does so for higher-income households as well.

The researchers caution that their analysis does not examine the extent to which medical spending may reflect choices made by the individual, such as when to enter a nursing home or whether to spend more on higher-quality care. They also suggest that future work incorporating spending by Medicare and private insurers would provide a more complete picture of medical spending by the elderly

The researchers gratefully acknowledge financial support from Norface Grant (TRISP 462-16-120) and from the Economic and Social Research Council (Centre for Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (RES-544-28-50001) and Inequality and the insurance value of transfers across the life cycle (ES/P001831/1)).