17th Annual Martin Feldstein Lecture, 2025: The Fiscal Future

N. Gregory Mankiw1

It is a great honor and delight to deliver this year’s Feldstein Lecture. I was never one of Marty’s students—I was educated not at Harvard, but at Princeton and MIT. Yet Marty nonetheless had a profound influence on my life and career.

As a freshman at Princeton in 1977, I took introductory microeconomics from the superb teacher Harvey Rosen, who later hired me to be his research assistant. Harvey was a recent PhD student of Marty’s, so even though I did not know it at the time, I entered the economics profession as Marty’s grandstudent.

Four years later, as a first-year student in MIT’s PhD program, I took a couple of courses from a promising, young assistant professor named Larry Summers, making me Marty’s grandstudent yet again. Then, in the summer of 1982, when President Reagan nominated Marty to chair the Council of Economic Advisers, I got a call from Marty—this was the first time we spoke. On Larry’s recommendation, Marty offered me a job on the Council staff. I quickly accepted and spent the academic year 1982–83 in Washington.

I worked for Marty a second time in 1985, after joining the Harvard faculty. Marty was then the head of Ec 10, Harvard’s full-year introductory course in economics. At the time, it was standard practice for new assistant professors to teach a section of Ec 10. Many assistant professors disliked the assignment, and the practice was soon abandoned. But I loved it. By covering the basics of micro and macro over the course of a year, Ec 10 served as a great reminder of why I fell in love with economics in the first place.

Years later, when I sat down to write my introductory textbook, Marty’s approach to the subject was firmly planted in my brain. In many ways, I wrote the book that Marty would have written if he had ever taken the time to do so. After my book was published in 1997, I was delighted that Marty’s Ec 10 was among the first courses to adopt it.

The Problem Ahead

The topic I would like to talk about today was close to Marty’s heart: the stance of fiscal policy and the path of government debt. Throughout his career, Marty advocated for greater saving, both private and public. As President Reagan’s chief economist, he warned about the adverse effects of large budget deficits, much to the chagrin of some other Reagan administration officials. If he were here with us today, I have no doubt that he would be concerned about the fiscal path the United States is now on.

Some years ago, The Wall Street Journal ran a cartoon that goes to the essence of the matter. A small child is coming home after getting off a school bus. As he opens the door to his house, he shouts to his parents, “What’s this I hear about you adults mortgaging my future?”

I like this cartoon not because it’s funny (it’s not, really) but because it succinctly summarizes the economics of government debt. Courses in macroeconomics examine how government debt affects interest rates, capital accumulation, trade deficits, and so on. But the starting point for all that analysis is a transfer of income between generations. In their personal capacity, parents cannot choose to live beyond their means and leave negative bequests to their children. As voters and citizens, however, parents can do exactly that, and Americans are now doing so in a big way.

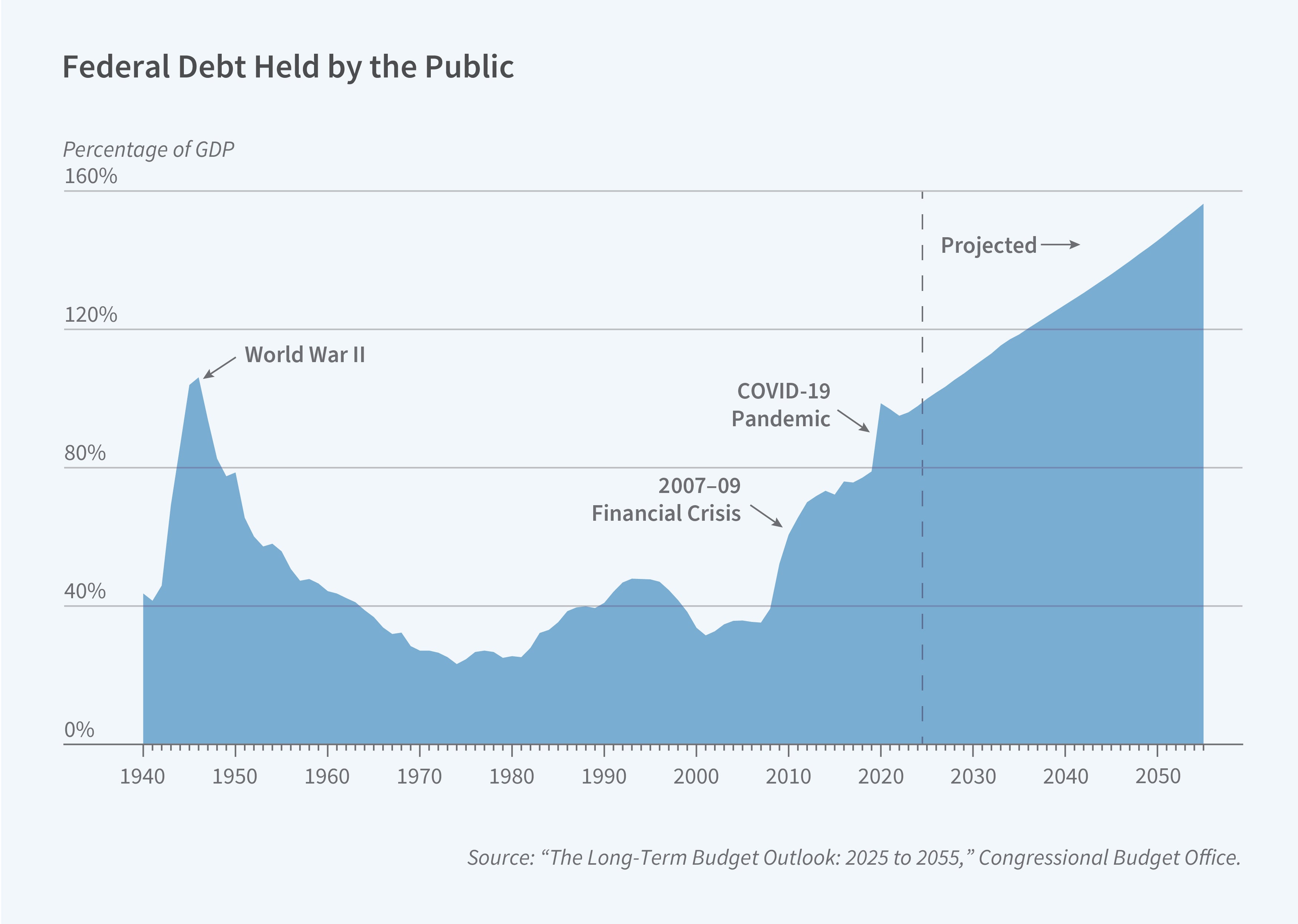

Historically, large changes in the debt-to-GDP ratio follow a simple pattern. The debt typically spikes upward during crises, such as major wars, deep economic downturns, or the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, when normalcy returns, the debt-to-GDP ratio gradually declines. This approach seems reasonable. Debt-financed spending during crises makes sense because it both provides some stabilization of aggregate demand and prevents large, temporary tax increases when spending needs are extraordinary. The policy also ensures that the cost of crises is shared among current and future generations.

The situation we now face differs substantially from this historical pattern. For those who follow economic policy debates, it is all too familiar. After massive budget deficits during the Great Recession of 2008–09 and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–21, the government debt as a percentage of GDP is near the historic high reached at the end of World War II. By itself, that is not necessarily alarming. In the few decades after 1945, the country managed to significantly reduce debt relative to income through a combination of economic growth, some inflation, and fiscal prudence.

But the trajectory ahead of us is not so benign. According to the 2025 projections of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the debt-to-GDP ratio will, under current law, continue to rise over the next three decades and reach 156 percent in 2055. There is, moreover, no end in sight to this increasing indebtedness.

Even more worrisome, this projection is optimistic. It assumes that the US economy will experience normal economic growth without a crisis like a major war, a deep recession, or another pandemic, which would push debt even higher. And it does not account for the so-called “Big Beautiful Bill” that President Trump just signed into law, which will steepen the ascent of government debt.

Herbert Stein once wisely said that “if something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” And I have no doubt that this path of a rising debt-to-GDP ratio will stop at some point. The open questions are how and when it will stop. That is what I would like to discuss with you today.

There are only five ways to stop this upward trajectory. They are (1) extraordinary economic growth, (2) government default, (3) large-scale money creation, (4) substantial cuts in government spending, and (5) large tax increases. I would encourage you to try to assign probabilities to these possible outcomes. Individually, each of these outcomes seems highly unlikely. But the probabilities you assign must sum to at least one. I say “at least” because more than one of these outcomes could occur.

Let’s consider each of these possibilities in turn.

Possibility 1: Extraordinary Growth

We begin with extraordinary economic growth. That would surely be the most benign of the possible outcomes. When the CBO makes its debt projections, it assumes future productivity will grow at about the rate we have experienced historically. Is it possible that we are entering a new golden age of more rapid growth due to new technologies like artificial intelligence and advances in biotechnology?

Yes, it’s possible. For example, the money manager Cathie Wood, CEO of ARK Invest, has suggested that because of these new developments, economic growth will soon accelerate from the 3 percent historical average to 6 to 8 percent going forward.2 Some people call this possibility the “technological singularity.”

My first thought when hearing such projections is, “that’s nuts.” Over the past few decades, we have seen the internet revolutionize how people work and lead their lives, yet economic growth has not been extraordinary. The effects of today’s nascent technologies will likely be similar: life-changing but not so transformative as to establish an entirely new growth path. In reaching this conclusion, I have been influenced—perhaps too much so—by the work of Robert Gordon on the rise and fall of American growth and Nicholas Bloom et al. on the hypothesis that ideas are getting harder to find.3,4 I hope I’m wrong and Cathie Wood is right, but I wouldn’t bet on it. It would surely be imprudent for fiscal policymakers to assume that rapid growth will come to their rescue.

Possibility 2: Government Default

The next possibility is that the government will default on its debts. For many people, such an event seems inconceivable. US government bonds are often considered among the safest of assets. But that view is, I believe, much too sanguine.

History offers many examples of sovereign default. Spain defaulted more than a dozen times between 1500 and 1800. More recently, we have seen defaults in Russia in 1998, Greece in 2015, Venezuela in 2017, and Argentina in 2001, 2014, and 2020.

The United States is not immune to the political and economic forces that can make default an attractive option. Recall that Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, argued forcefully and successfully against default on Revolutionary War debts. But other prominent figures at the time opposed Hamilton’s plans and were more open to the possibility of partial default. James Madison thought that speculators, who had purchased the debt from the original lenders at a deep discount, should not be rewarded with full repayment.

More importantly, the United States, in fact, once defaulted on its debt. As Sebastian Edwards discusses in his brilliant book American Default, many US bonds in the 1930s had gold clauses that ensured their value in gold bullion.5 When President Franklin Roosevelt decided to pull the nation off the gold standard, he recognized how expensive these gold clauses would be. So, he decided to abrogate them. Not surprisingly, the decision to unilaterally rewrite these bond contracts led to a court battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court. In a 5–4 vote, the court sided with Roosevelt. In the midst of the Great Depression, that outcome may have been desirable. But without doubt, it was a partial default, as the title of Edwards’s book suggests.

You might naturally ask, What about today? Might any modern-day president ever entertain the possibility of default? Here is Donald Trump back in 2016 when he was initially a candidate for president and a journalist asked him about how he would handle the government debt.6

“I’m the king of debt. I’m great with debt. Nobody knows debt better than me. I’ve made a fortune by using debt, and if things don’t work out, I renegotiate the debt. I mean, that’s a smart thing, not a stupid thing.”

“How do you renegotiate the debt?” the journalist asked.

“You go back and you say, hey guess what, the economy crashed. I’m going to give you back half.”

If President Trump’s second term has proved anything, it is that he is willing to expand the Overton Window (the range of policies and arguments deemed acceptable in political discourse). Remember this exchange the next time someone says that a default on US government debt is unimaginable.

Possibility 3: Large-Scale Money Creation

It is sometimes said that a nation with debt denominated in its own currency never needs to default because it can always print money to repay its creditors. That’s true, but I don’t find the thought nearly as reassuring as some who advance it.

We have lots of historical experience with what happens when central banks use monetary expansion to finance reckless fiscal policy. The German hyperinflation of the 1920s is the most famous example. More recently, a similar story played out in Zimbabwe. From 2006 to 2009, the typical unit of currency in the country went from 50 Zimbabwe dollars to 100 trillion Zimbabwe dollars. And even the Z$100 trillion notes were soon worthless. I recall seeing a picture from the time taken in a Zimbabwe restroom cautioning people not to use the toilets to flush newspapers, cardboard, or Zim dollars. It is a well-known theorem of monetary economics that when people must be told not to flush their cash down the toilet, monetary policy is not optimal.

Such hyperinflation is, of course, a form of default in the sense that bond holders are paid back in worthless currency. But it is an especially destructive way to default. High inflation wreaks havoc throughout the economy. Given the choice, it may be better for a government to default explicitly rather than embark on an implicit default in the form of hyperinflation.

Nonetheless, hyperinflations occur when fiscal policymakers don’t want to come to grips with their own folly and monetary policymakers are too weak to resist the pressures from fiscal policy. Such a regime, sometimes called “fiscal dominance,” doesn’t always lead to hyperinflation like that in Germany and Zimbabwe. There are more moderate cases, such as the 75 percent annual inflation that Turkey has experienced in recent years. That outcome is better than hyperinflation, but it is hardly desirable.

It is worth noting that Donald Trump has made clear that he believes the president should have more authority over monetary policy—an idea most economists reject. Last month, Mr. Trump even publicly mused about appointing himself to the Fed. And he has consistently pushed for more expansionary monetary policy. Over the next several years, the conflict between fiscal and monetary policymakers could well become a defining event. It is unclear whether future Federal Reserves will have the fortitude to stand up to a demanding and belligerent president. So, I wouldn’t rule out the high-inflation scenario.

Possibility 4: Substantial Spending Cuts

The next way to put fiscal policy on a sustainable path is to enact a substantial cut in government spending. Many people favor this alternative, at least until they consider the details of what it means.

President Trump began his second term by empowering Elon Musk and the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). That initiative has led to one of the largest reductions in the federal workforce in US history. I am personally troubled by the chaotic approach that DOGE has taken. It seems to be following the famous Silicon Valley injunction, coined by Mark Zuckerberg, to “move fast and break things.” This mantra may work for a startup, but it’s not the right approach to running one of the world’s largest and most important governments.

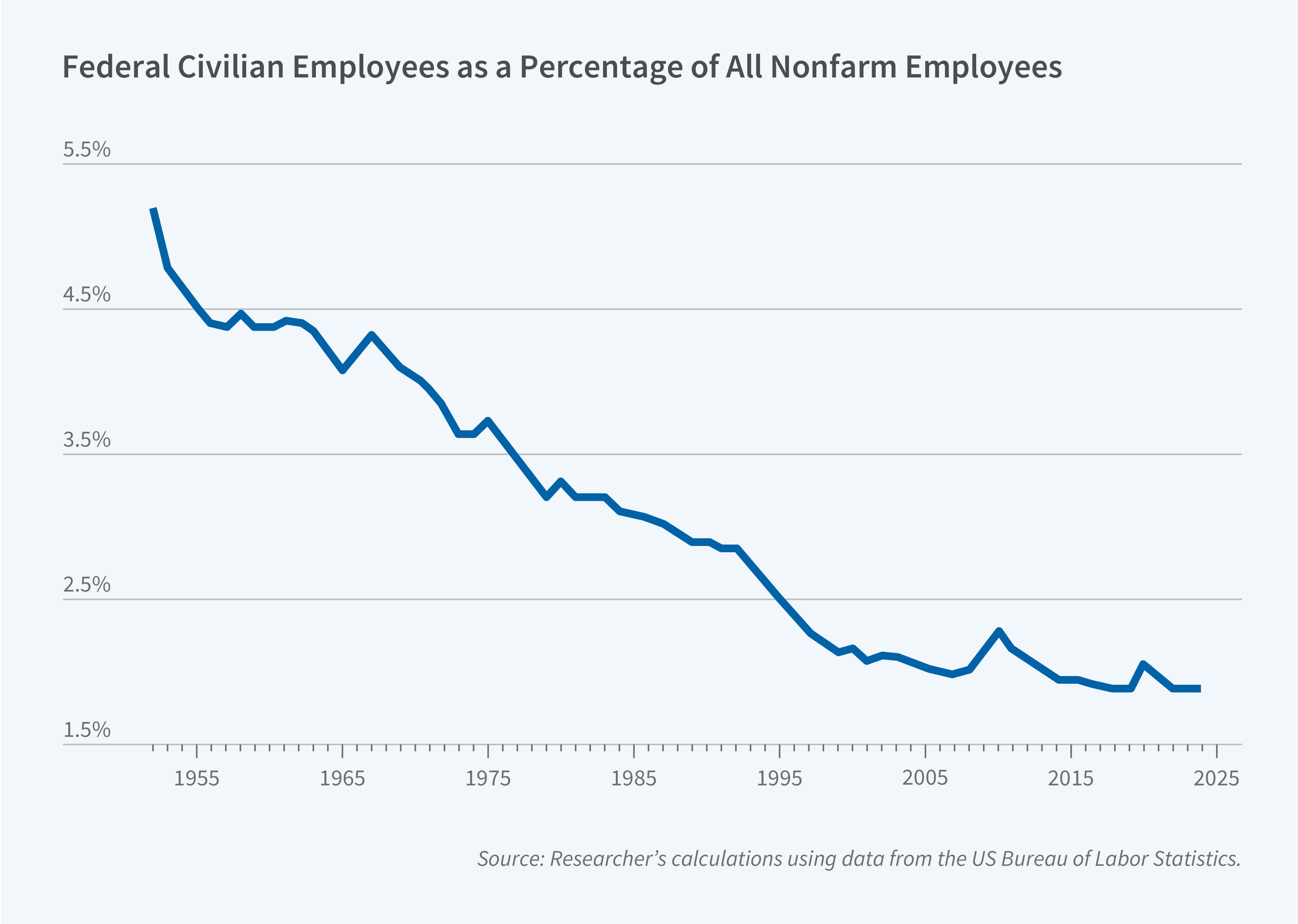

Regardless of one’s views of the DOGE downsizing initiative, there was always reason to believe that its impact on the overall budget would be limited. The compensation of civilian government employees makes up only about 4 percent of the federal budget. Moreover, contrary to some people’s perceptions, the size of the federal workforce is not bloated by historical standards. Federal civilian employees made up about 4.5 percent of the economy’s total nonfarm employment in the 1950s. Today, it’s under 2 percent.

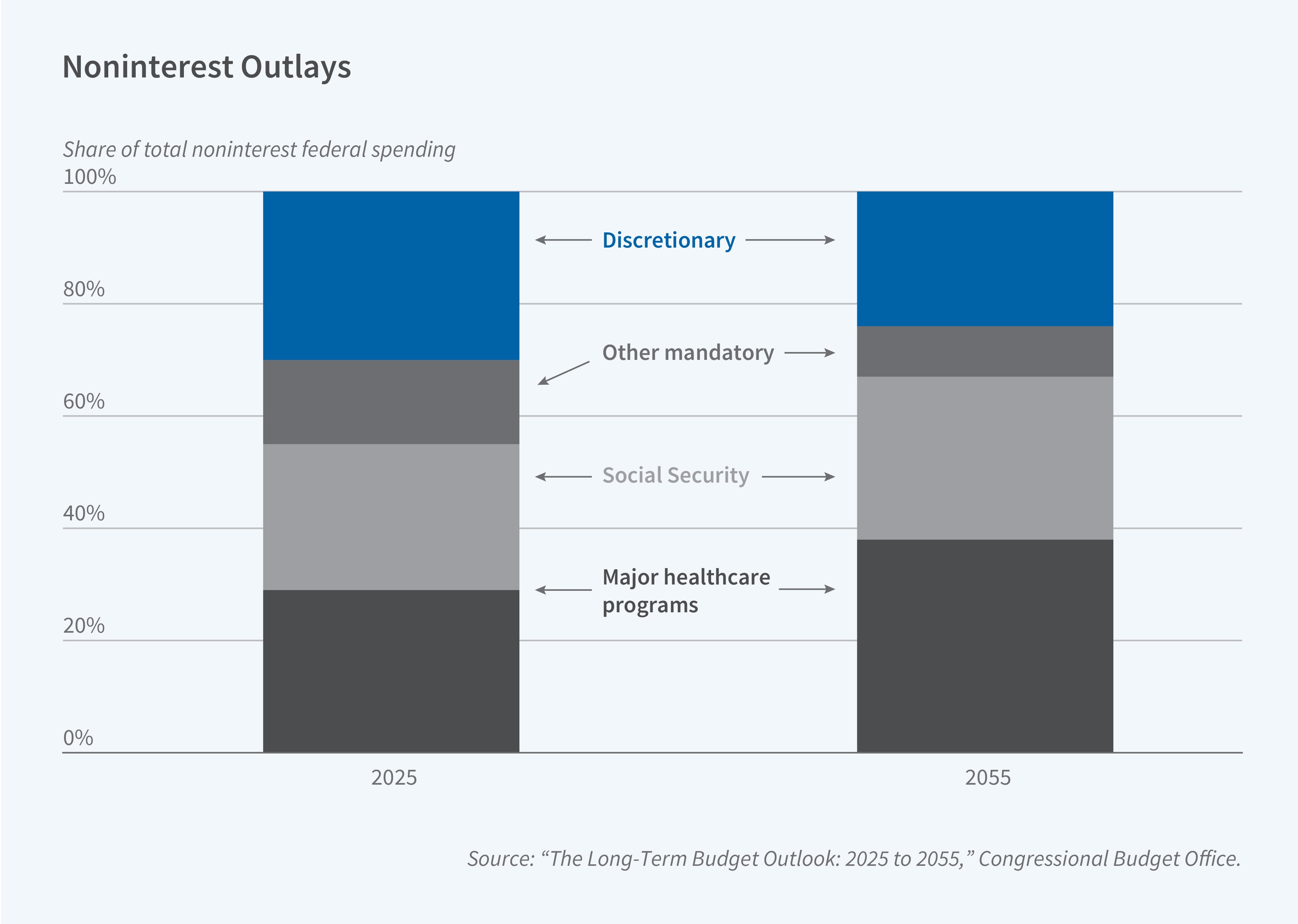

When thinking about the federal budget, it is best to recall a quip from Peter Fisher, a Treasury official in the George W. Bush administration, who once called the federal government “an insurance company with an army.” Defense spending constitutes about 13 percent of the federal budget. More than half of federal spending is on Social Security and health programs. That percentage has risen over time and is projected to continue rising in the years to come as more of the baby boom generation retires and starts drawing benefits.

Enacting large cuts in these entitlement programs is politically treacherous. When Paul Ryan was Speaker of the House, he endorsed some modest cuts in these programs. In response, the opposition party ran television ads showing an actor who resembled Ryan pushing a grandmother in a wheelchair off a cliff. My sense is that this ad campaign was largely successful. That explains why President Trump has said throughout his political career, including as recently as February 2025, that Social Security and Medicare benefits are not going to be touched, other than to investigate fraud.

All this leads me to conclude that in light of what Americans expect from their government, substantial spending cuts are probably out of the question.

Possibility 5: Large Tax Hikes

This brings me to the last way that the United States might respond to its unsustainable fiscal trajectory: raising taxes. I view this as the most likely outcome in the long run, for two reasons.

First, each of the first four ways out of this problem—extraordinary growth, government default, high inflation, or massive spending cuts—seems either implausible or unacceptable. We might well get some of these, but we won’t get enough of them to put fiscal policy on a sustainable path.

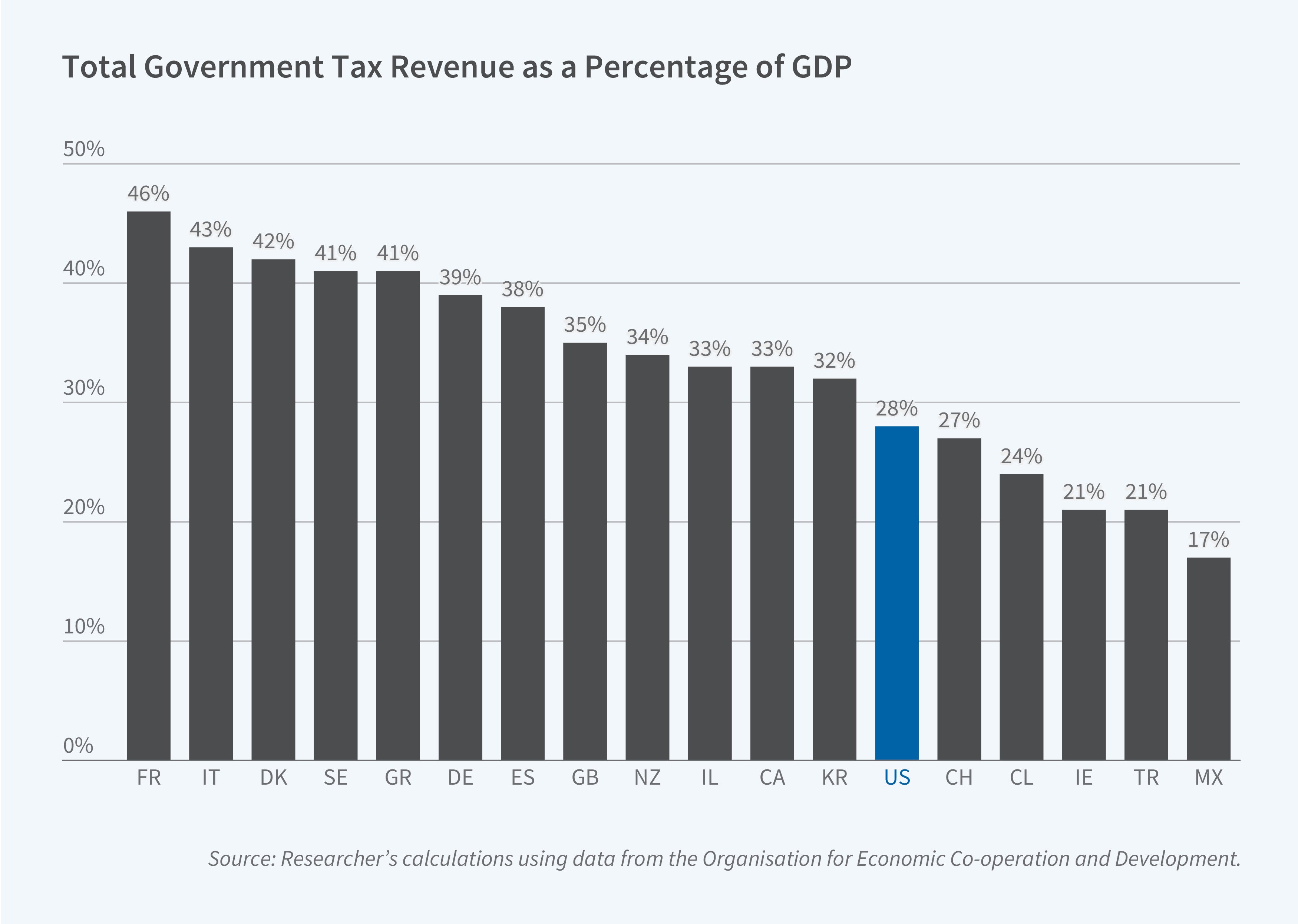

Second, the United States is now a low-tax country compared with its peers. In most aspects of life, regression toward the mean is a strong and pervasive force, and this context could be no different. According to OECD data (for 2022), governments at all levels in the United States collect only about 28 percent of GDP in tax revenue, compared with 35 percent in the United Kingdom, 41 percent in Sweden, 43 percent in Italy, and 46 percent in France. The OECD average is 34 percent.

A natural question is how much US taxes must increase to close the impending fiscal gap. Larry Kotlikoff looks at the present value of the infinite future of spending and taxes and estimates a gap of about 7 percent of GDP.7 My own rough calculation suggests a somewhat smaller number. The CBO estimates that the primary deficit will average 2 percent of GDP over the next 30 years.8 Add to that about 1 percent of GDP for the Big Beautiful Bill that was just signed into law. And assuming the interest on government debt exceeds the growth rate by 1 percentage point, add another 1 percent of GDP to service the existing debt (roughly 100 percent of GDP) and stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. That yields a fiscal gap of roughly 4 percent of GDP.

This gives us some sense of the magnitude of the task ahead. To close a fiscal gap of 4 percent of GDP with only increased revenue, the United States would need to raise overall tax revenue by about 14 percent. That is a huge tax hike, but it would bring us only about halfway toward the level of taxation that prevails in the United Kingdom. US taxes would remain below the OECD average and well below the levels in France, Italy, and Sweden. From a strictly economic standpoint, that is entirely feasible.

To be sure, most European nations use their higher tax revenue to pay for public services that Americans often finance privately. The most significant example is healthcare. If the United States were to both close its fiscal gap and provide universal healthcare, a much larger tax increase would be required, bringing the US tax burden close to the levels in countries like Italy and Sweden. In this sense, the future of fiscal policy is intertwined with the future of health policy. But for now, let’s set aside the possibility of major reform of the US healthcare system.

The big question is whether a tax hike large enough to close the fiscal gap is politically possible. I am reminded of an old chestnut about Washington politics. It has been said that the United States has two political parties—the stupid party and the evil party. Sometimes, the two parties get together and do something that is both stupid and evil. They call that bipartisanship.

In that vein, there is now a bipartisan consensus about a central tenet of tax policy. The Republicans don’t want to raise taxes on anyone (except universities with large endowments). The Democrats want to raise taxes only on the richest 1 percent. So, the two parties essentially agree that 99 percent of Americans should not have to endure higher taxes. This bipartisan consensus is the roadblock between where we are and where we need to go.

If a sizable tax increase is inevitable, as I believe it is, we must look beyond the top 1 percent of the income distribution. Typical high-income taxpayers living in places like New York or California (where many reside) are already taxed very heavily. Adding together federal income taxes, state income taxes, payroll taxes, and sales taxes, the marginal tax rate on the ordinary income of the highest earners is about 55 percent. Of course, some loopholes that benefit the richest Americans are natural targets for reform. Examples include the taxation of carried interest, the treatment of capital gains in opportunity-zone investments and qualified small business stock, and the Section 199A deduction for certain pass-through businesses. But we shouldn’t expect to get 4 percent of GDP in additional revenue just from those at the top of the income pyramid. Attempting to do so would be highly inefficient given the high marginal rates most of them already face.

It is probably not even feasible to raise enough revenue from this small group. According to my back-of-the-envelope calculations, increasing the marginal tax rate on the richest 1 percent by 15 percentage points (so the top rate goes from 55 to 70 percent) would raise only about a quarter of the revenue needed. And this calculation assumes, optimistically and unrealistically, that people won’t change their behavior in response to higher tax rates. In practice, increasing taxes on only the most affluent would raise much less revenue. That’s why closing the fiscal gap will require broadly shared sacrifice.

For a Solution, Look Abroad

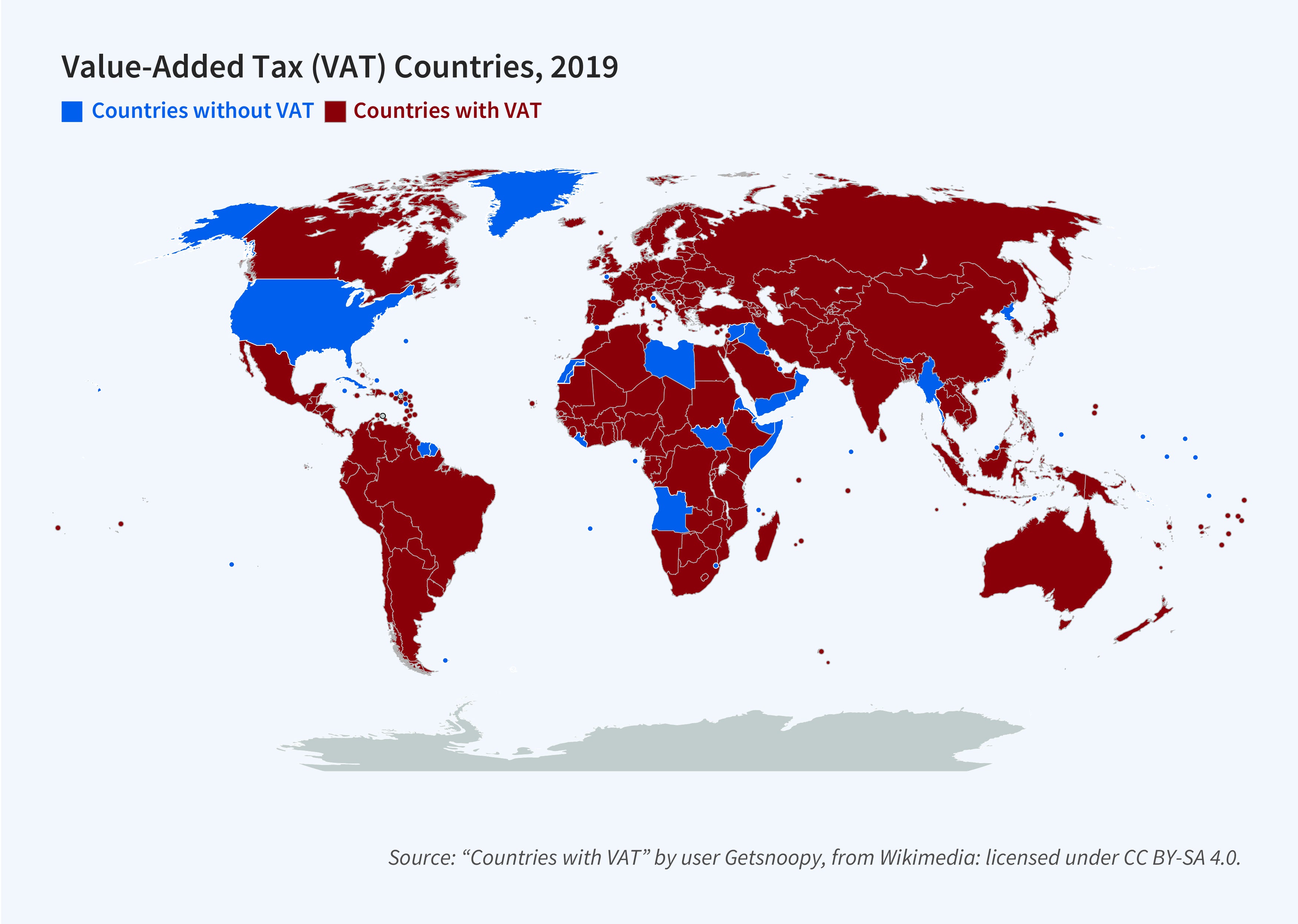

The natural candidate is a value-added tax (VAT). Most nations around the world have value-added taxes, and these taxes have shown themselves to be remarkably efficient. Among OECD countries, VAT revenues average about 7 percent of GDP, which is more than enough to close the US fiscal gap. One virtue of a VAT is that it taxes consumption rather than income. My reading of the vast literature on optimal taxation is that consumption is the better tax base because taxing it does not distort the margin between consumption today and consumption in the future.9

A VAT would, however, increase the distortion at the labor-leisure margin. But absent lump-sum taxes, that can’t be avoided if the government is to raise more revenue. Ed Prescott suggested that higher tax rates in Europe are the main reason that Europeans work less than Americans—a view I find plausible.10 Yet others have proposed other explanations for the high level of European leisure. Alberto Alesina, Ed Glaeser, and Bruce Sacerdote emphasize the role of unions, and Olivier Blanchard says that there are different preferences on the two sides of the Atlantic.11,12 If the United States ever institutes a sizable VAT, it will provide a natural experiment to test Prescott’s hypothesis. If he is right and Americans start working less, we’ll need a somewhat larger tax increase than I have estimated.

As of now, there is no obvious support among our nation’s political leaders for a VAT. But the idea is not completely beyond the pale. Back in 2009, Nancy Pelosi briefly floated the idea when she was Speaker of the House, though no legislation was ever introduced.13 And in 2016, when Paul Ryan was Speaker of the House, he advocated for a destination-based cash flow tax, based on work by Alan Auerbach and Michael Devereux, which in some ways resembles a VAT.14,15

At times, I have even wondered whether Donald Trump’s unconventional views on economics might lead him to favor a VAT, though not for the reasons I would advance. He has argued that the value-added taxes of other nations are a trade barrier like a tariff. That’s not true, of course. Back in 1989, Marty Feldstein and Paul Krugman wrote a paper debunking this common fallacy—and they weren’t the first to do so.16 Put simply, a VAT is trade neutral because it applies equally to imports and domestically produced goods.17 Nonetheless, Mr. Trump’s misunderstanding, together with his affection for tariffs, might make him open to a US VAT.

For a VAT proposal to make its way through Congress and onto the president’s desk, the minds of many politicians would need to change. In an ideal, well-functioning democracy, a blue-ribbon commission would study the unyielding budget arithmetic, offer a menu of realistic solutions, and convince voters that there are no easy choices. Once the voters were persuaded, our elected leaders would quickly follow.

In the democracy we have, the path to fiscal reform could well be less deliberate and more painful. Change might occur only when the bond market loses faith in American political institutions. If one day the bond vigilantes wake up and start viewing the United States as a large version of Greece or Argentina, they will stop buying US debt at normal rates of interest. Congress will have no choice but to face the music, regardless of the political consequences.

The Day of Reckoning

So how soon might this day of reckoning arrive? Back in 2011, I wrote about these issues in The New York Times.18 The article took the form of a presidential speech that might be given during a future debt crisis. The United States was about to accept a bailout from the International Monetary Fund, whose headquarters had relocated to Beijing. The conditions for the bailout consisted of substantial and painful cuts in government spending together with higher taxes on all but the poorest Americans.

I set the date for this hypothetical speech 15 years in the future—that is, in 2026. That date was somewhat arbitrary. Like many economists at the time, I saw that US fiscal policy was unsustainable, but I did not see any evidence that the bond market was about to hold policymakers’ feet to the fire. So 15 years seemed a reasonable guess.

Soon after the Times published the article, I received an email from Alice Rivlin, the great policy economist and founding director of the CBO. She wrote, “Great piece in the NYT on the Debt. But I doubt the market will give us 15 years. Maybe 5?”

With the benefit of hindsight, we can say that Alice was wrong. Fourteen years have now passed without a US debt crisis. As Rudi Dornbusch famously remarked, “In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then happen faster than you thought they could.” Ernest Hemingway made a similar point. In his novel The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt. He replied, “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.”

I wouldn’t be shocked if the United States continued along the path of a gradually rising debt-to-GDP ratio for another 15 years. But I also wouldn’t be shocked if the bond vigilantes suddenly attack much sooner. Cracks in the fiscal foundation have already started to appear. In May of this year, Moody’s downgraded US government debt below AAA status, citing large deficits and rising interest costs. Now, none of the major credit rating agencies gives US debt its top rating.

A Concluding Thought

I began this lecture with a cartoon. Let me conclude with another, one of my favorites from The New Yorker. It takes place in the Oval Office, with the president’s advisers huddling around the Resolute Desk. They tell him, “Our deficit-reduction plan is simple, but it will require a great deal of money.”

This is the situation we now confront. Putting the federal government on a sustainable path is, from a purely economic standpoint, relatively simple. If a random group of NBER research associates could be appointed as a committee of monarchs, they could solve the problem in a long weekend.

In the real world, the solution must come from our elected representatives, who know that any solution will impose significant pain on the current generation of voters. For most politicians, getting reelected is their highest priority. Enacting good policy is farther down the list. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that a solution won’t come until the financial markets leave policymakers with no other choice. That scenario would be unpleasant for nearly everyone.

But if Marty Feldstein were here with us today, he would likely give us reason to be more optimistic. His copious body of op-eds—many written with Kate—was premised on the conviction that a better-educated public would embrace a more rational economic policy. Perhaps that can occur this time. The United States experienced substantial declines in government debt relative to GDP, without major economic disruptions, from 1790 to 1830, from 1870 to 1910, and from 1945 to 1975. Maybe the fiscal future will indeed be so benign. I don’t yet see the path from here to there through the political thicket, but I hope it is out there somewhere, ready to be found.

Endnotes

I am grateful to Larry Ball, Alan Blinder, Charlie Covit, Karen Dynan, Doug Elmendorf, Deborah Mankiw, and Jane Tufts for helpful comments.

“The Journey from Monetary Shock to an Innovation-Led Economic Boom,” Wood C. ARK Invest Market Commentary, March 7, 2024.

The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living since the Civil War, Gordon RJ. Princeton University Press, 2016.

“Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” Bloom N, Jones CI, Van Reenen J, Webb M. American Economic Review 110(4), April 2020, pp. 1104–1144.

American Default: The Untold Story of FDR, the Supreme Court, and the Battle over Gold, Edwards S. Princeton University Press, 2018.

“Trump: ‘I’m the King of Debt’,” Nelson L. POLITICO, June 22, 2016.

“Fiscal Child Abuse,” Kotlikoff L. Economic Matters by Laurence Kotlikoff, May 27, 2025.

“The Long-Term Budget Outlook: 2025 to 2055,” Congressional Budget Office, March 27, 2025.

“Optimal Taxation in Theory and Practice,” Mankiw NG, Weinzierl M, Yagan D. Journal of Economic Perspectives 23(4), Fall 2009, pp. 147–174.

“Why Do Americans Work So Much More Than Europeans?” Prescott EC. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 28(1), July 2004, pp. 2–13.

“Work and Leisure in the US and Europe: Why So Different?” Alesina AF, Glaeser EL, Sacerdote B. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2005 20, April 2006, pp. 1–64.

“The Economic Future of Europe,” Blanchard O. Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(4), Fall 2004, pp. 3–26.

“Pelosi Open to a Value-Added Tax,” Thompson D. The Atlantic, October 7, 2009.

“Cash-Flow Taxes in an International Setting,” Auerbach AJ, Devereux MP. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(3), August 2018, pp. 69–94.

“Year in Review: News Analysis: The Rise and Fall of the Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax,” Sapirie M. Tax Notes, December 18, 2017.

“International Trade Effects of Value-Added Taxation,” Feldstein M, Krugman P. In Taxation in the Global Economy, Razin A, Slemrod J, editors, pp. 263–282. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

“‘Reciprocal’ Tariffs Make No Sense,” Irwin DA. The Wall Street Journal, February 13, 2025.

“It’s 2026, and the Debt is Due,” Mankiw NG. The New York Times, March 26, 2011.