Public Health Efforts and the US Mortality Transition

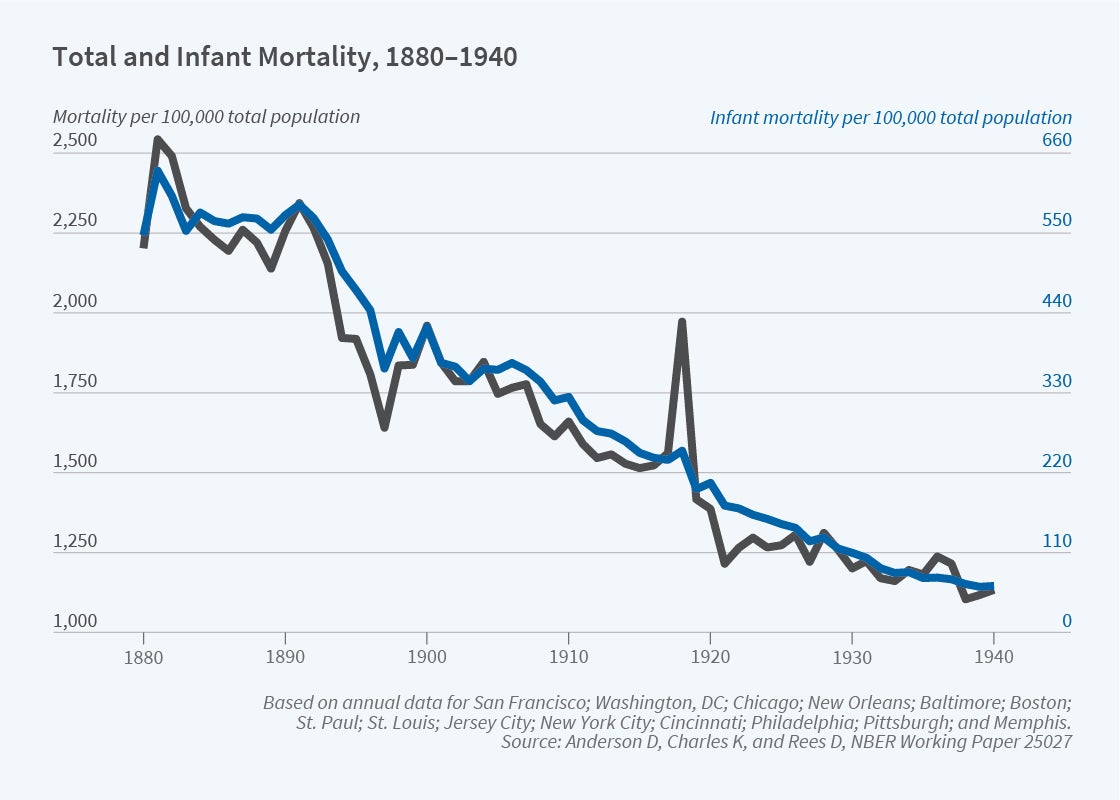

In the mid-1800s, mortality rates in US and Western European cities were much higher than those in rural areas. Since then, urban mortality rates have fallen dramatically. Driven by reductions in infectious diseases and diseases of infancy and childhood, this phenomenon is often referred to as the mortality transition and has been recognized as one of the most significant developments in the history of human welfare.1 By the 1940s, the mortality “penalty” from living in a major urban center had all but disappeared in modern, developed countries.2

Economists originally attributed the mortality transition to increases in income, the onset of modern economic growth, and improved nutrition.3 However, more recent analyses have stressed the importance of public health efforts, particularly efforts to supply clean water to the residents of major American cities.4

In a series of papers, we revisited the causes of the US urban mortality decline at the turn of the 20th century. We explored the role of clean water technologies and estimated the effectiveness of other public health efforts that were seen as vital to reducing food-related and waterborne diseases, including the building of sewage treatment plants; requirements that municipal milk supplies meet strict bacteriological standards; and requirements that milk come from tuberculin-tested cows. We also explored the determinants of the Black-White infant mortality gap in the first four decades of the 20th century and studied the extent to which public health efforts contributed to the narrowing of this gap. Finally, we estimated the effects of the US campaign against tuberculosis (TB) on pulmonary TB mortality during the early 1900s. The US anti-TB movement pioneered many of the strategies of modern public health campaigns, but its effectiveness had not been studied in a systematic fashion by previous researchers.

Public Health Efforts and the Decline in Urban Mortality

Previous research suggests that the US mortality transition was driven primarily by public health interventions aimed at reducing food-related and waterborne illnesses.5 However, because the same city would often implement several interventions within a span of a few years, it has been difficult for researchers to isolate the effect of any single intervention, especially when taking a case-study approach.

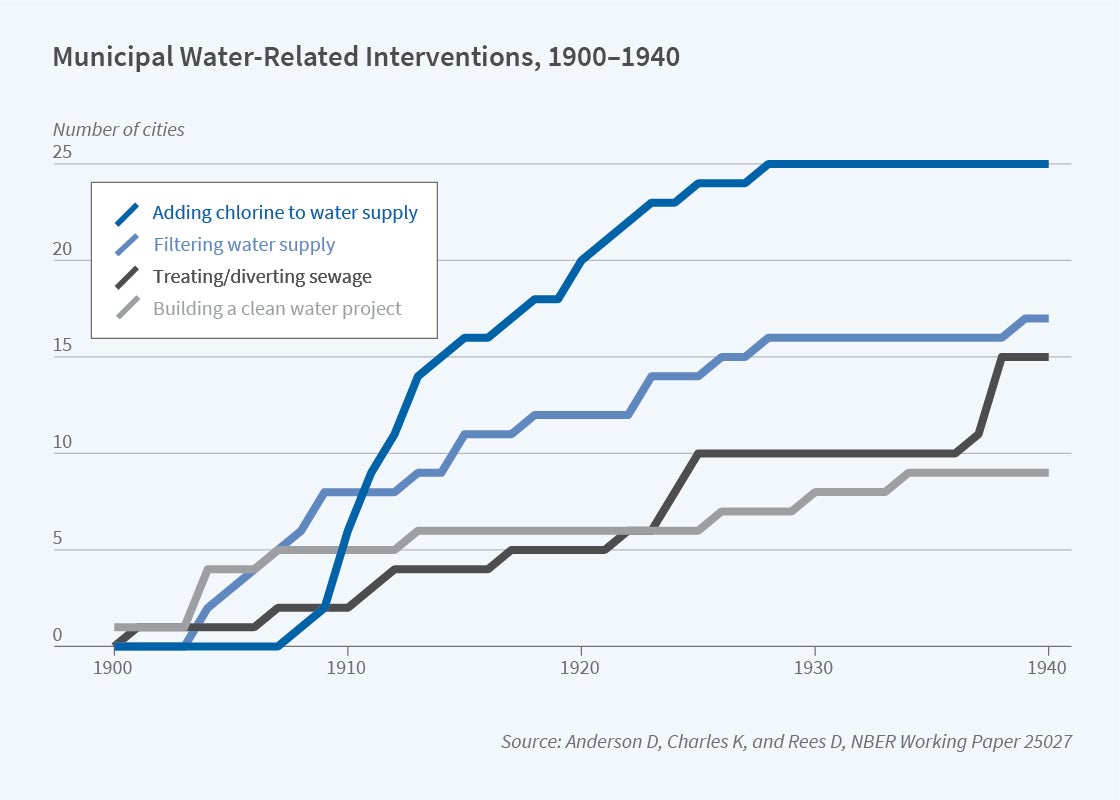

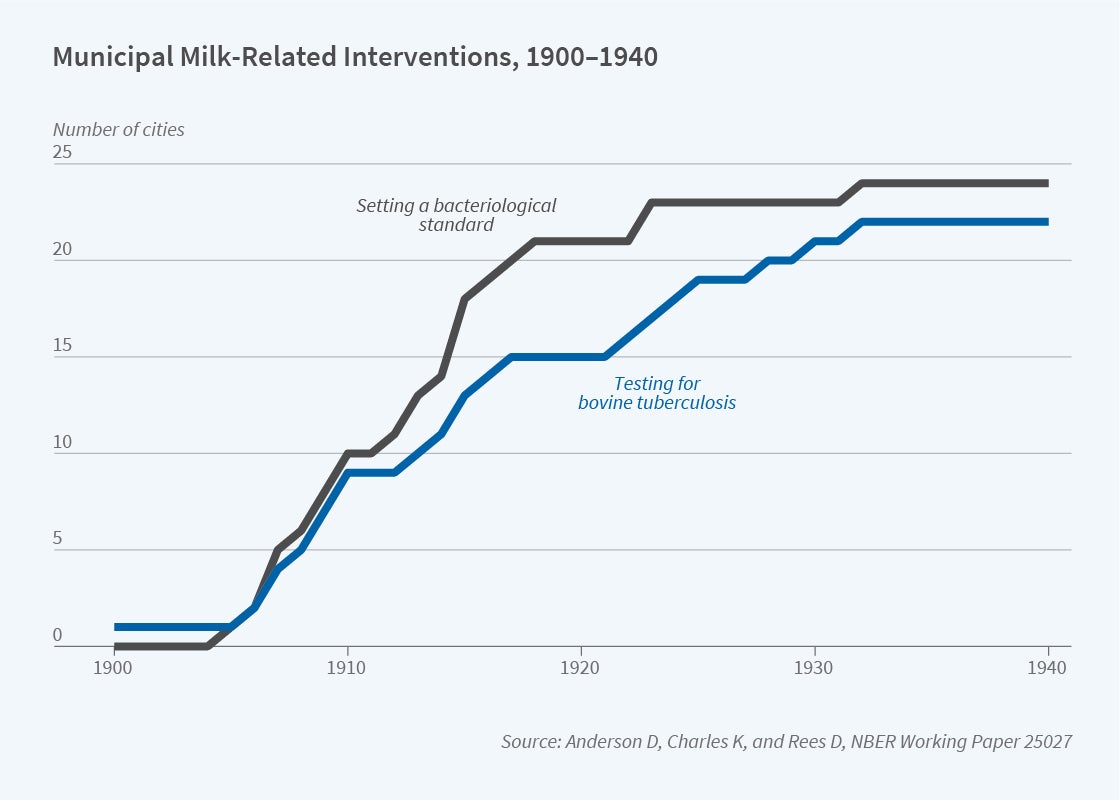

Using data from the US Census Bureau’s Mortality Statistics and Vital Statistics of the United States on 25 major American cities for the period 1900–1940, we conducted a statistical horse race to distinguish the effects of ambitious, often very expensive, public health interventions.6 Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the rollout of the water- and milk-related interventions, respectively, for our sample of cities.

Consistent with the results of several previous studies,7 we found that filtering the municipal water supply led to large reductions in typhoid mortality. Although we found no evidence that adding chlorine to drinking water, building sewage treatment plants, or testing dairy cows for TB were effective, filtering the water supply was also associated with an 11 to 12 percent decrease in infant mortality and a 14 percent reduction in diarrhea/enteritis mortality. While these estimates were measured with precision, they were not nearly large enough to explain the overall declines in infant and diarrheal mortality observed during the period 1900–1940. Our findings are inconsistent with David Cutler and Grant Miller’s widely cited finding8 that water filtration was a large contributor to the mortality decline. 9

Water Purification Efforts and the Black-White Infant Mortality Gap

In another study, we explored the relationship between clean water technologies and the Black-White infant mortality gap during the period 1906–1938.10 Werner Troesken observed that urban Blacks and Whites lived in close proximity — “almost side by side” — at the turn of the 20th century.11 He famously hypothesized that, because of this lack of residential segregation, it was costly to deny Blacks access to clean water, and that fear of waterborne diseases spreading from Blacks to Whites “played a role in motivating cities to install relatively equitable sewer and water systems.”12 More generally, it is theoretically ambiguous whether health inequalities are exacerbated or mitigated by technological innovation. Exclusive technologies can be subject to “elite capture,” while there is evidence that less expensive “breakthrough” technologies disproportionately benefit poorer, underprivileged individuals.13

Consistent with Troesken’s hypothesis, we found that chlorinating the water supply, which was relatively cheap, had no observable effect on the White infant mortality rate (IMR), but led to a 9 percent reduction in the Black IMR and a 10 percent reduction in the Black-White IMR ratio — our measure of the Black-White infant mortality gap. Moreover, we found that adding chlorine to the water supply narrowed the Black-White infant mortality gap, at least in part, through its effect on diarrheal disease. Specifically, we found that chlorination led to a 17 percent reduction in diarrhea/enteritis mortality among Black children under the age of two. The construction of water filtration plants, by contrast, was equally effective at reducing Black and White death rates.

Why would chlorination only affect Black infant mortality? One potential explanation is that it mattered more for Black families because, on average, their children were more likely to suffer from nutritional deficiencies, making them relatively vulnerable to waterborne infections. Another possibility is that Black families did not have the resources to disinfect or boil their water prior to chlorination. Consistent with this argument, Troesken found a stronger positive association among Blacks than among Whites between bacteria counts in municipal water supplies and waterborne disease mortality.14

The Phenomenon of Summer Diarrhea and Its Waning

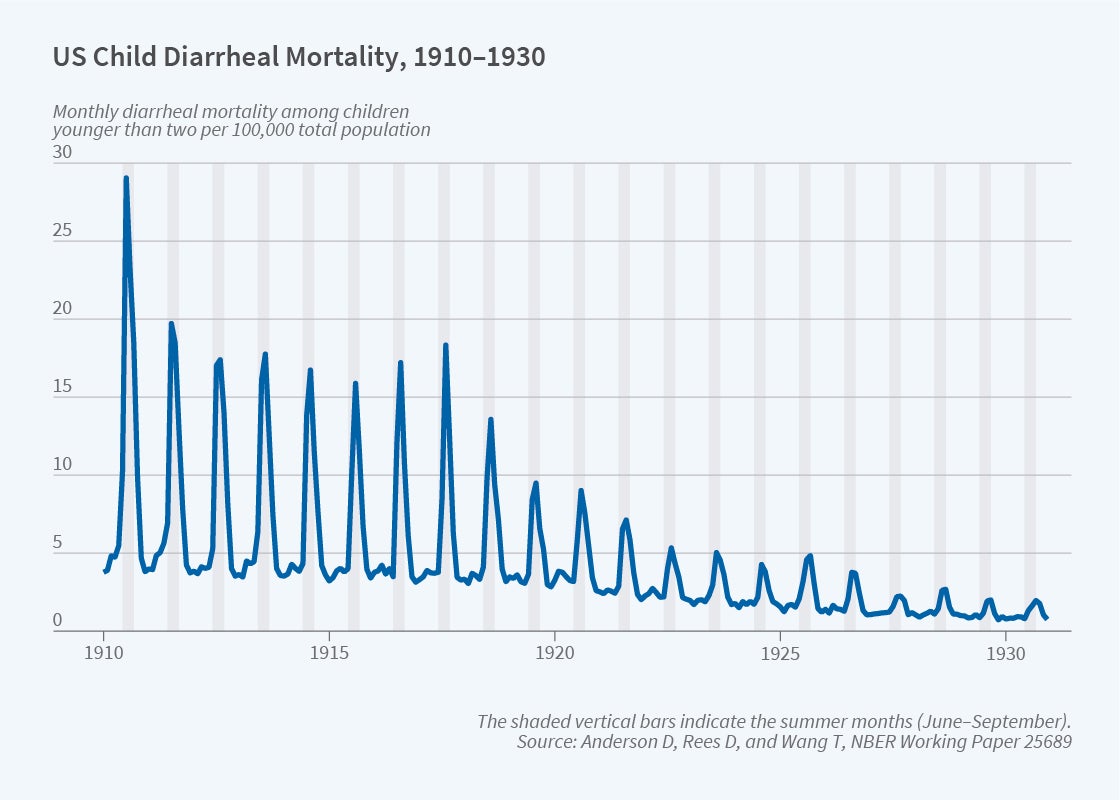

At the start of the 20th century, diarrheal deaths among US infants and children surged every summer. This seasonality waned considerably by 1930 (Figure 3). Economists and historians have argued that summer diarrhea was eventually controlled by public health interventions,15 especially municipal-level efforts to purify water and milk supplies.

Building upon the results described above, Anderson, Rees, and Tianyi Wang explored whether water filtration and other municipal public health interventions contributed to the diminishing severity of summer diarrhea among children under age two.16 We found that the construction of a water filtration plant was associated with a 15 percent reduction in diarrheal mortality during the non-summer months, which is consistent with the hypothesis that transmission occurred through contaminated water. Perhaps surprisingly, there was little evidence that filtration affected diarrheal mortality during the months of June through September, suggesting that the phenomenon of summer diarrhea was driven by contaminated food or person-to-person contact. Improvements in the refrigeration chain, better nutrition, or some combination of these and other factors may have contributed to the dramatic decline in summer diarrheal deaths among infants and children in the United States shown in Figure 3.

The US Anti-Tuberculosis Movement

In 1900, 194 out of every 100,000 Americans died of TB, making it the second-leading cause of death behind pneumonia/influenza. By 1930, the TB mortality rate had fallen dramatically to 71 per 100,000 persons.17 Scholars have proposed several explanations for this decline, including improved nutrition, better living conditions, reduced virulence, and herd immunity. The introduction of basic public health measures is another possible and popular explanation.

Widely regarded as the first public health campaign, the US anti-tuberculosis movement was remarkable in its scope and intensity. During the early 1900s, hundreds of state and local TB associations sprang up across the United States. These associations distributed educational materials and provided financial support to sanatoriums and TB hospitals where TB patients were isolated from the general public. The anti-TB movement was also characterized by the passage of legislation at the state and local levels to, for instance, ban public spitting and forbid the use of common drinking cups, require physicians to report TB cases to public health officials, and mandate the disinfection of premises after the removal of a TB patient.

Using data on pulmonary TB mortality for over 500 municipalities, we explored the effectiveness of the public health measures championed by the anti-TB movement for the period 1900–1917.18 We found evidence that requiring TB cases to be reported to local health officials led to a modest reduction in pulmonary TB mortality. We also found that the establishment of a state-run sanatorium led to an almost 4 percent reduction in pulmonary TB mortality. By contrast, there was little evidence that other anti-TB measures were effective.

To gauge the overall effect of the anti-TB movement, we calculated what the pulmonary TB mortality rate would have been had no anti-TB measures been adopted. Our findings suggest that the anti-TB measures at the turn of the 20th century did not contribute in a meaningful way to the marked decline in TB mortality in the United States.

What’s Next?

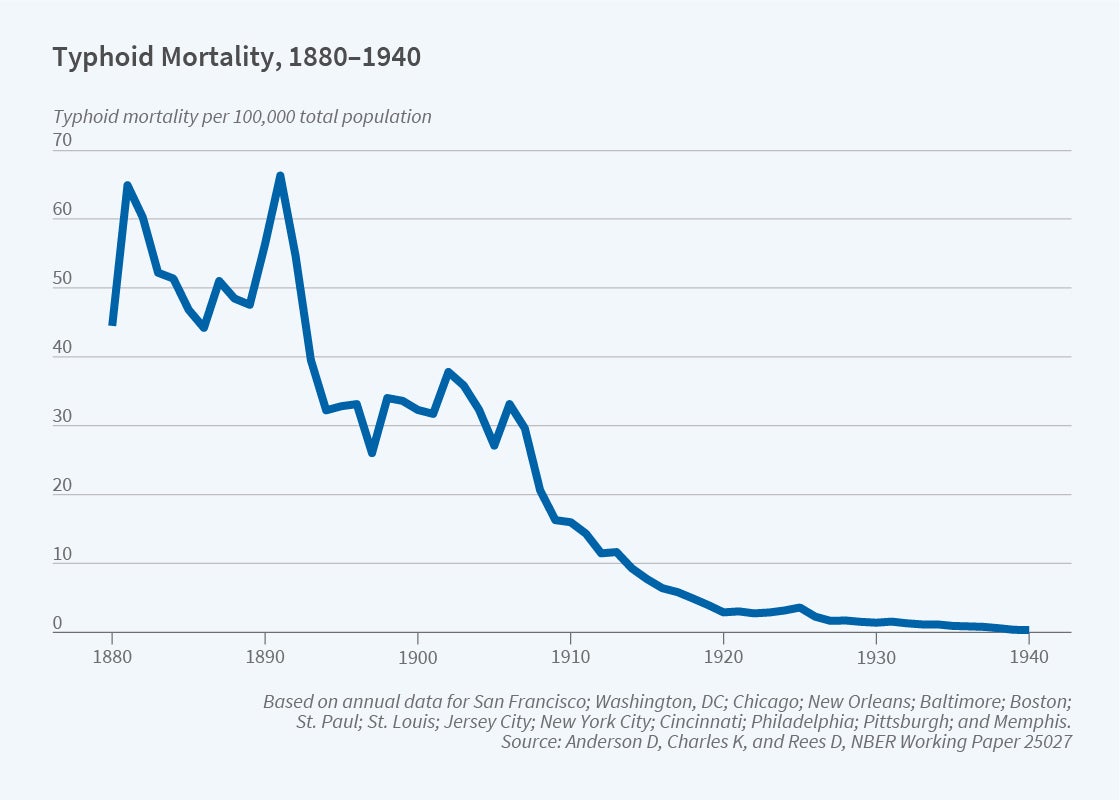

Figure 4 shows total and infant mortality trends over the period 1880–1940 for a sample of 14 US cities. It is based on data from the US Census Bureau’s Mortality Statistics and Vital Statistics of the United States for the period 1900–1940, and mortality data we recently gathered from the archives at the National Library of Medicine for the period 1880–1899. Figure 5 shows typhoid mortality trends for the same years for these 14 cities.

The research projects described above provide little evidence to support the notion that public health measures drove the mortality transition in the United States. It is, of course, possible that other factors such as nutrition and income were responsible for the steep decline in mortality starting in the mid-19th century, but it is worth noting that each of our research projects used data from the early 20th century, when the mortality transition was well underway. Our plan is to analyze the determinants of urban mortality in the 19th century, when public health innovations included the building of extensive sewer systems and the establishment of pathology laboratories by local health departments. Refrigeration, in the form of manufactured ice, also made its first appearance in the last decades of the 19th century. Our future research will explore the effect of these and other innovations on the mortality transition.19

D. Mark Anderson, Kerwin Kofi Charles, and Daniel I. Rees are conducting collaborative research on how municipal-level public health efforts contributed to the decline in urban mortality in the United States, with a focus on the pre-1900 period. They also are investigating the relationship between hospital desegregation efforts and the Black-White infant mortality gap in the Deep South during the Civil Rights Era.

Endnotes

“Health and the Economy in the United States, from 1750 to the Present,” Costa D. NBER Working Paper 19685, June 2014, and Journal of Economic Literature 53(3), September 2015, pp. 503–570; The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100: Europe, America, and the Third World, Fogel R. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

“The Urban Mortality Transition in the United States, 1800–1940,” Haines M. NBER Historical Working Paper 134, July 2001, and Annales de Démographie Historique 101(1), 2001, pp. 33–64.

“Reasons for the Decline of Mortality in England and Wales during the Nineteenth Century,” McKeown T, Record RG. Population Studies 16(2), November 2011, pp. 94–122; The Modern Rise of Population, McKeown T. New York, Academic Press, 1976; “New Findings on Secular Trends in Nutrition and Mortality: Some Implications for Population Theory,” Fogel R. Handbook of Population and Family Economics 1(A), 1997, pp. 433–481.

“The Determinants of Mortality,” Cutler D, Deaton A, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 11963, January 2006, and Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3), Summer 2006, pp. 97–120; “Health and the Economy in the United States, from 1750 to the Present,” Costa D. NBER Working Paper 19685, June 2014, and Journal of Economic Literature 53(3), September 2015, pp. 503–570.

“The Determinants of Mortality,” Cutler D, Deaton A, Lleras-Muney A. NBER Working Paper 11963, January 2006, and Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3), Summer 2006, pp. 97–120; “Water and Chicago’s Mortality Transition, 1850–1925,” Ferrie J, Troesken W. Explorations in Economic History 45(1), 2008, pp. 1–16.

“Public Health Efforts and the Decline in Urban Mortality,” Anderson D, Charles K, Rees D. NBER Working Paper 25027, December 2018, and forthcoming as “Re-examining the Contribution of Public Health Efforts to the Decline in Urban Mortality,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Water, Race, and Disease, Troesken W. Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004; “The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth-Century United States,” Cutler D, Miller G. NBER Working Paper 10511, May 2004, and Demography 42(1), February 2005, pp. 1–22; “Typhoid Fever, Water Quality, and Human Capital Formation,” Beach B, Ferrie J, Saavedra M, Troesken W. Journal of Economic History 76(1), February 2016, pp. 41–75.

“The Role of Public Health Improvements in Health Advances: The Twentieth Century United States,” Cutler D, Miller G. NBER Working Paper 10511, May 2004, and Demography 42(1), February 2005, pp 1–22.

Cutler and Miller analyzed data from 13 major American cities for the period 1900–1936. Using their data and specification, we found that their estimated effect of filtration on total mortality was halved if US Census Bureau population estimates were used to consistently calculate the total mortality rate for the full data sample and that correcting transcription errors reduced the estimated effect on infant mortality by two-thirds.

“Water Purification Efforts and the Black-White Infant Mortality Gap, 1906–1938,” Anderson D, Charles K, Rees D, Wang T. NBER Working Paper 26489, November 2019, and Journal of Urban Economics 122, March 2021, 103329.

Water, Race, and Disease, Troesken W. Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004.

“The Limits of Jim Crow: Race and the Provision of Water and Sewerage Services in American Cities, 1880–1925,” Troesken W. Journal of Economic History 62(3), October 2002, pp. 734–772.

“Technological Progress and Health Convergence: The Case of Penicillin in Post-War Italy,” Alsan M, Atella V, Bhattacharya J, Conti V, Mejía-Guevara I, Miller G. NBER Working Paper 25541, February 2019.

Water, Race, and Disease, Troesken W. Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004.

Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929, Meckel R. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990; “Information and the Impact of Climate and Weather on Mortality Rates during the Great Depression,” Fishback P, Troesken W, Kollmann T, Haines M, Rhode P, Thomasson M. In The Economics of Climate Change: Adaptations Past and Present, Libecap G, Steckel R, editors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

“The Phenomenon of Summer Diarrhea and Its Waning, 1910–1930,” Anderson D, Rees D, Wang T. NBER Working Paper 25689, October 2019, and Explorations in Economic History 78, October 2020, 101341.

“The Burden of Disease and the Changing Task of Medicine,” Jones D, Podolsky S, Greene J. New England Journal of Medicine 366(25), June 2012, pp. 2333–2338.

“Was the First Public Health Campaign Successful?” Anderson D, Charles K, Olivares C, Rees D. NBER Working Paper 23219, March 2017, and American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(2), April 2019, pp. 143–175.

“Public Health Efforts and the Decline in Urban Mortality,” Anderson D, Charles K, Rees D. NBER Working Paper 25027, December 2018, and forthcoming as “Re-examining the Contribution of Public Health Efforts to the Decline in Urban Mortality,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.