Do Tax Incentives for Research Increase Firm Innovation?

Small and medium-sized firms in the U.K. doubled R&D spending and increased patenting by 60 percent in response to tax incentives.

Beginning in the early 1980s, business R&D spending as a share of GDP began to decline in the United Kingdom, while it was rising in most other OECD countries. Concerned about falling behind in innovation and growth, the U.K. government in 2000 launched a tax incentive program to encourage R&D. It was largely targeted at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In 2008, the government expanded this program.

In Do Tax Incentives for Research Increase Firm Innovation? An RD Design for R&D (NBER Working Paper 22405), Antoine Dechezleprêtre, Elias Einiö, Ralf Martin, Kieu-Trang Nguyen, and John Van Reenen report that the tax relief program not only spurred innovation by the firms that were its direct beneficiaries, but that it also had positive spillover effects on technologically related firms.

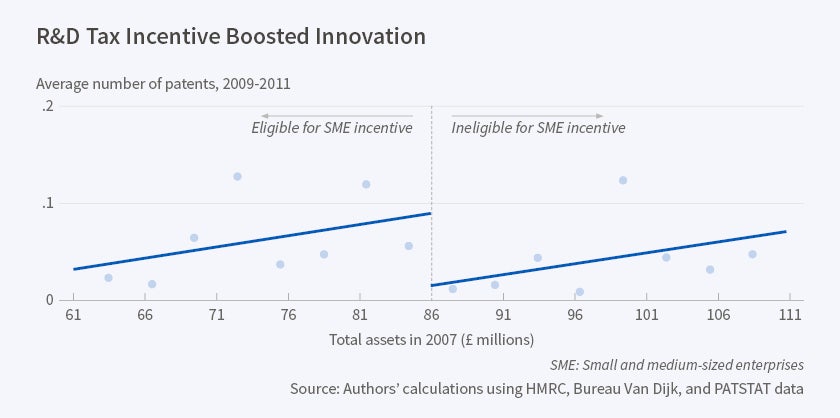

The researchers focused on a provision of the 2008 policy reform that changed the eligibility standards for receiving special tax treatment. The asset threshold for qualification was doubled, so that after 2008, firms with assets as high as £86 million were redefined as SMEs for the purpose of the program.

Eligible SMEs could deduct an amount equal to 175 percent of their R&D expenses from their taxable income and, even if their taxable income was negative, they could still receive tax credits. By comparison, the deduction rate was 130 percent for large firms, without the option of tax credits if their taxable income was negative.

The researchers examined data from 2006 through 2011, before and after the tax change, and compared the patterns of R&D spending by firms with assets just below and just above the new £86 million threshold. After 2008, companies that qualified for the special SME tax treatment sharply increased R&D spending compared with those whose assets were too large, just above the £86 million threshold, for them to qualify. The firms that qualified doubled R&D spending and increased patenting by 60 percent relative to those that were not eligible. The researchers found no evidence that the additional patents were of lower quality. They also estimated that R&D tax-price elasticity was 2.6, meaning that a 10 percent drop in the effective cost generated a 26 percent increase in spending. They cautioned against generalizing this figure over the entire range of companies, noting that tax subsidies tend to have greater impact on smaller firms in part because they have less access to credit.

The researchers did not find evidence that firms reclassified existing activities as R&D or expanded relatively inconsequential projects. Extrapolating from their findings, they estimated that in the absence of tax relief, aggregate business R&D spending would have been 10 percent lower in the U.K. during the period under study. Further, they calculated that each £1 of taxpayer subsidy led to £1.7 in spending on R&D.

—Steve Maas