Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection in Health Insurance

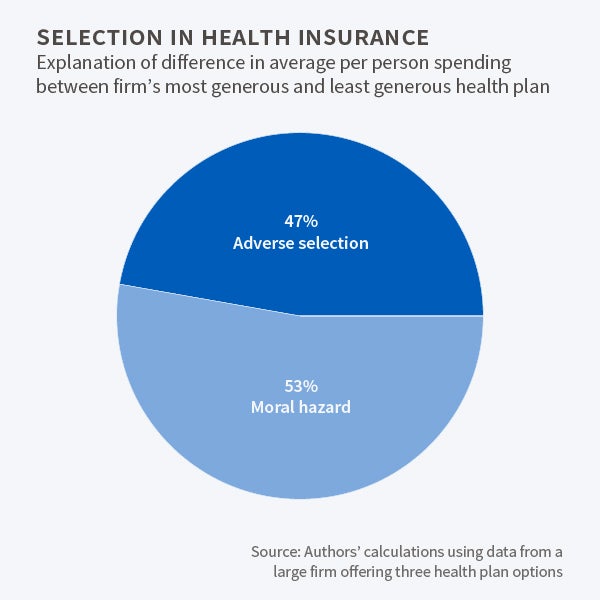

Enrollee health status explains 47 percent of the difference in health spending of those who selected the most generous and least generous insurance plans at a large firm.

A central challenge in designing health insurance plans is providing coverage that will provide for participants' unexpected health care needs without encouraging unnecessary spending.

When insured individuals bear a smaller share of their medical care costs, they are likely to consume more care. This is known as "moral hazard." In addition, when individuals who have a choice among insurance plans select their plan, those who are more likely to require care tend to choose more generous plans. This is known as "adverse selection."

The challenge for economists is to estimate whether someone who spends more in generous plans does so because the plan covers more or because such a plan attracts individuals with greater underlying health needs.

In Disentangling Moral Hazard and Adverse Selection in Private Health Insurance (NBER Working Paper 21858), David Powell and Dana Goldman examine the effect of price changes on medical spending and the selection of workers across health insurance plans when a large manufacturing firm switches from offering just one employee insurance plan to a choice of three.

In 2005, the last year the single plan was in effect, enrollees paid no deductible, had a 20 percent co-insurance rate, and there was no cap on out-of-pocket medical expenditures. Subsequently, the company offered three plans that were similar in all respects other than their deductibles, co-insurance rates, and out-of-pocket maximums. As of 2007, the most generous plan featured a $250 deductible, a 10 percent co-pay, and a $1,250 out-of-pocket cap; the least generous had an $800 deductible, a 20 percent co-pay, and a $4,000 cap.

Predictably, those who enrolled in the most generous plan spent the most on health care. The researchers sought to isolate the relative significance of adverse selection and moral hazard in accounting for differences in their expenditures.

In analyzing how enrollees responded to the choice of plans, the researchers controlled for demographic factors that affect health spending, such as age, gender, and the relationship of dependents to employees. They also took account of enrollee spending in 2005, when everyone was under the same plan.

The researchers developed statistical procedures that minimized the influence of plan participants with extreme health out-comes—very little care, or a great deal—to assess the impact of plan choice. They found favorable selection in the least generous plan, which attracted an unusually healthy population, and adverse selection in the more generous plans.

Exemplifying favorable selection, 28 percent of the enrollees in the least generous plan spent under $182 on medical care during the year. Had selection bias not been a factor in enrollment, the researchers estimate only 20 percent of the enrollees would have been so frugal. The study estimates that had the entire sample enrolled in the least generous plan, annual premiums for this plan would have had to rise by $1,000 in order to cover the greater health spending of those who had chosen other, more generous plans.

The researchers calculate that adverse selection added $773 in per-person costs to the most generous plan. Enrollees had to pay an additional $60 a month in premiums in order for this plan to break even.

Overall, the study concludes that moral hazard accounted for $2,117, or 53 percent, of the $3,969 difference in spending between the most and least generous plans. It attributes the remaining 47 percent to adverse selection.

—Steve Maas