Cross-Country Redistribution from Eurozone Monetary Policy

The eurozone is a monetary union without a fiscal union: Each national central bank is ultimately backed by its own government. When the European Central Bank (ECB) engages in cross-border lending or asset purchasing, the gains and losses are borne unevenly by taxpayers in different countries. In What Does It Take? Quantifying Cross-Country Transfers in the Eurozone (NBER Working Paper 34311), Yi-Li Chien, Zhengyang Jiang, Matteo Leombroni, and Hanno Lustig demonstrate that the ECB’s large-scale bond purchases and bank loans have led to significant transfers.

Before the 2009 sovereign debt crisis, private investors, especially German banks, lent directly to Italy and other southern economies at market rates that reflected default and currency risk. When those private flows froze, the ECB stepped in, first through emergency lending and later through large-scale bond purchases. Each national central bank intervened in credit markets, buying primarily its own government’s bonds to stabilize markets and suppress borrowing costs.

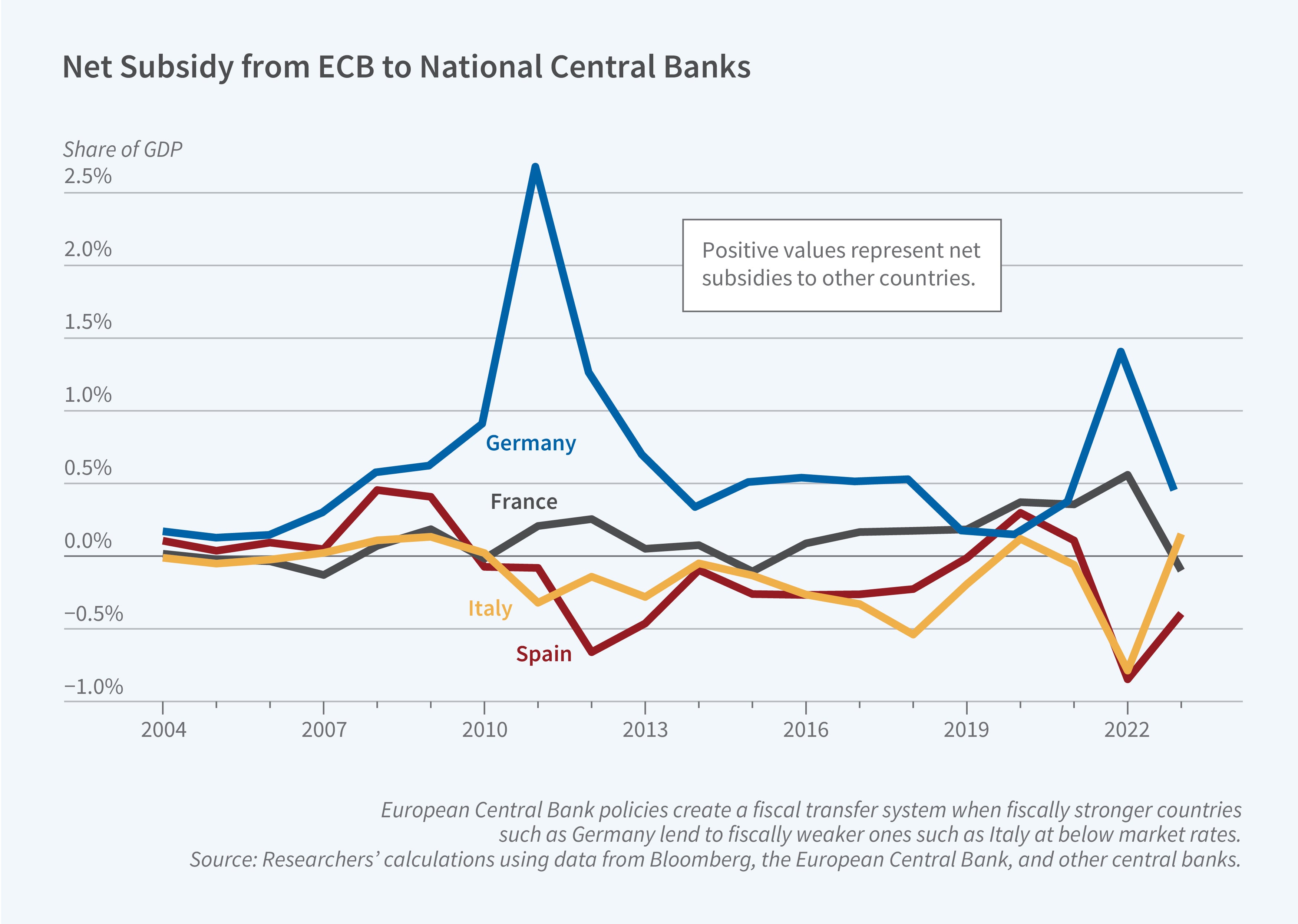

This arrangement created an asymmetry. When the Banca d’Italia purchased Italian bonds from German banks, it paid with newly created reserves that ultimately accumulated at the Deutsche Bundesbank, where banks preferred to hold them because reserves held in the German central bank were viewed as safer, should the eurozone ever fracture, than those at other central banks. Italy’s central bank, unable to attract reserve holders, financed its purchases by borrowing from Germany’s central bank through the ECB’s TARGET2 settlement system. The borrowing rate was the ECB policy rate, which was well below the market rate that Italy would otherwise have faced. This created a hidden subsidy for Italy and a corresponding burden on Germany.

The researchers calculate that between 2004 and 2023, the subsidies from Germany to other eurozone countries amounted to close to 11 percent of its GDP. Italy and Spain received the equivalent of 5.9 percent and 7.2 percent of their GDPs, respectively. Part of those gains were passed through to domestic banks via cheap lending programs. Adding the ECB’s own impact in reducing sovereign yields increases the estimated transfers further, to nearly 13 percent of GDP for Germany and roughly 8 to 10 percent for Italy and Spain.

The contrast between cross-jurisdiction redistribution in the eurozone and the US is notable. When the Federal Reserve buys US government bonds, any associated gains or losses are shared across all states because the US is both a monetary and fiscal union. In Europe, however, the risks and benefits of monetary interventions fall unevenly across national lines. German taxpayers bear the credit and redenomination risks of Italian and Spanish debt.

In short, unlike the US Federal Reserve system, where reserves are treated uniformly across districts, the eurozone’s monetary system reflects investors’ concerns about potential fragmentation. These concerns contribute to a persistent core–periphery divide in reserve holdings. Ultimately, the results indicate that while the ECB’s monetary policies are designed to stabilize financial markets, they also function as a channel of implicit fiscal redistribution across eurozone member states.

- Abby Hiller