Public Agricultural R&D and Brazilian Economic Development

Global R&D investment is concentrated in a handful of high-income countries. When it is targeted to their specific needs, it may have limited productivity benefits elsewhere. In Public R&D Meets Economic Development: Embrapa and Brazil’s Agricultural Revolution (NBER Working Paper 34213), researchers Ariel Akerman, Jacob Moscona, Heitor S. Pellegrina, and Karthik Sastry investigate whether public R&D in a developing country can overcome this problem of technology mismatch. They focus on Embrapa (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária), a large-scale agricultural research corporation that was launched in Brazil in 1973.

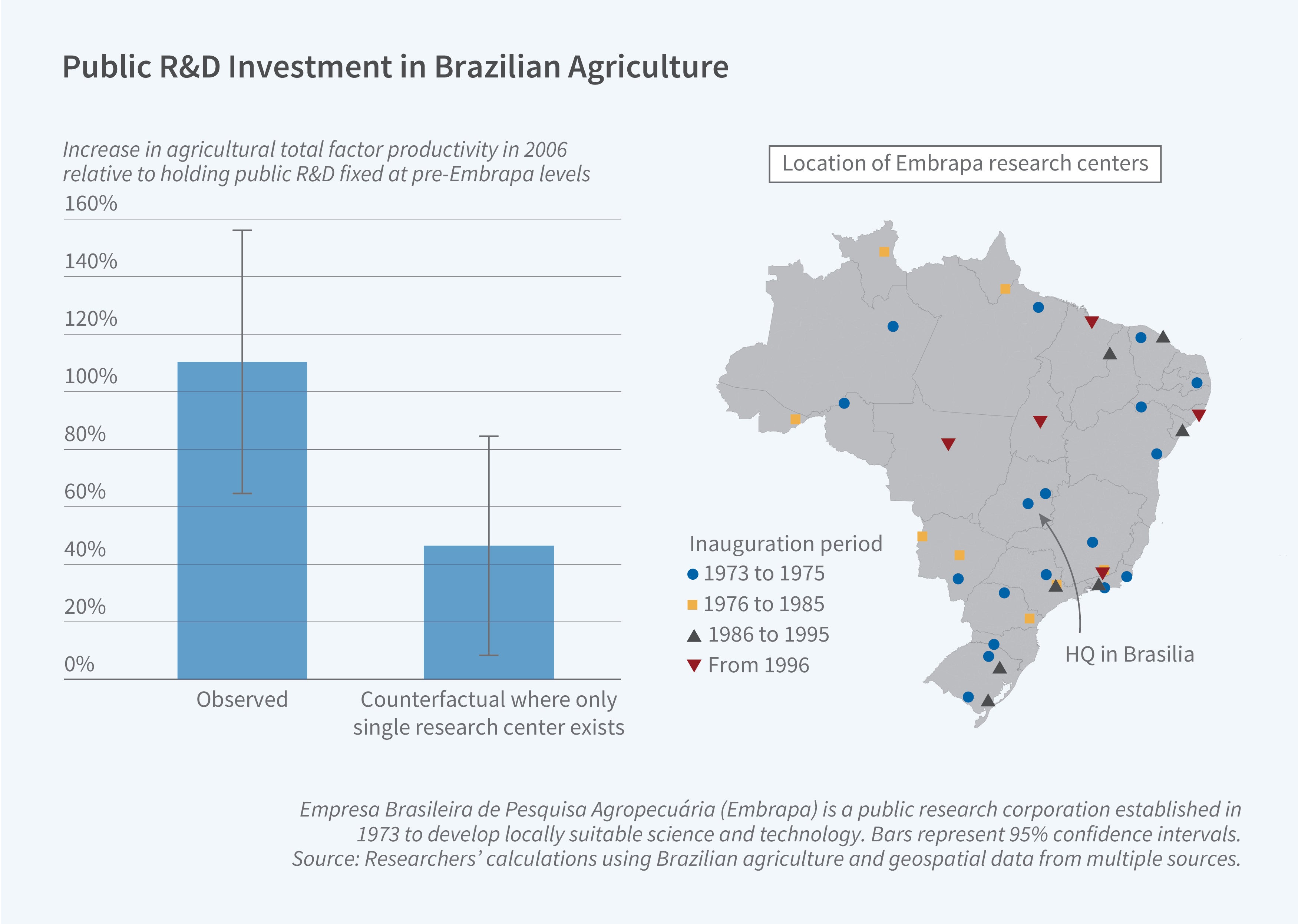

By investing in agricultural research about local ecological conditions, Brazil’s Embrapa more than doubled national agricultural productivity.

The researchers identify two ways in which Embrapa influences Brazilian agriculture. First, it alters the focus, trajectory, and productivity of agricultural science and technology development. Embrapa scientists are more likely than their peers to conduct research that is relevant to Brazil’s ecology and major staple crops. This was accomplished by building new research centers in all of Brazil’s diverse ecological zones, where researchers could focus on understanding local ecosystem characteristics, and was achieved while also increasing research productivity. Moreover, Embrapa also shifted the research focus for the broader Brazilian research community, inducing non-Embrapa researchers to tailor their focus to the local ecology.

Second, Embrapa substantially raised agricultural productivity in regions that were ecologically similar to Embrapa’s labs and hence positioned to benefit from its innovation. An increase in Embrapa exposure of 1 cross-sectional standard deviation leads to a 12 percent gain in agricultural productivity. This result is not driven by proximity to research centers but rather facilitated by the ecological relevance of technologies developed by Embrapa. There are outsize effects of Embrapa exposure on both the adoption of technology and the productivity of crops that Embrapa explicitly targets.

The researchers attribute a 110 percent increase in Brazilian agricultural productivity to Embrapa, with a benefit-cost ratio of 17. The corporation’s geographic scope plays an important role: The researchers estimate that if Embrapa operated out of one large headquarters, as opposed to multiple geographically dispersed stations, the gain would have been 47 rather than 110 percent.

— Laurel Britt