Job Mismatch and Early Career Outcomes

How does misalignment between a worker’s cognitive skills and their job demands affect their career trajectory? Despite the importance for labor markets, it has been challenging to isolate the causal impacts of being over- or underqualified because workers self-select into occupations. This makes it difficult to determine whether performance differences stem from mismatch or from other factors that influence job choice.

In Job Mismatch and Early Career Success (NBER Working Paper 34215), researchers Julie Berry Cullen, Gordon B. Dahl, and Richard De Thorpe overcome this challenge using data from the US Air Force, where new enlistees are assigned to over 130 different jobs based partly on test scores. They calculate a worker’s relative ability as the difference between their own Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) score and the average score of others in the same job. Those with positive relative ability are categorized as having an “ability surplus,” while those with negative values have an “ability deficit.” To isolate plausibly exogenous variation in surplus and deficit, they construct instruments by simulating job assignments based on job availability and the quality of other recruits entering at the same time.

Quasi-random job assignments in the US Air Force suggest that overqualified workers outperform others in the same job but have higher turnover, while underqualified workers show greater commitment but are less productive.

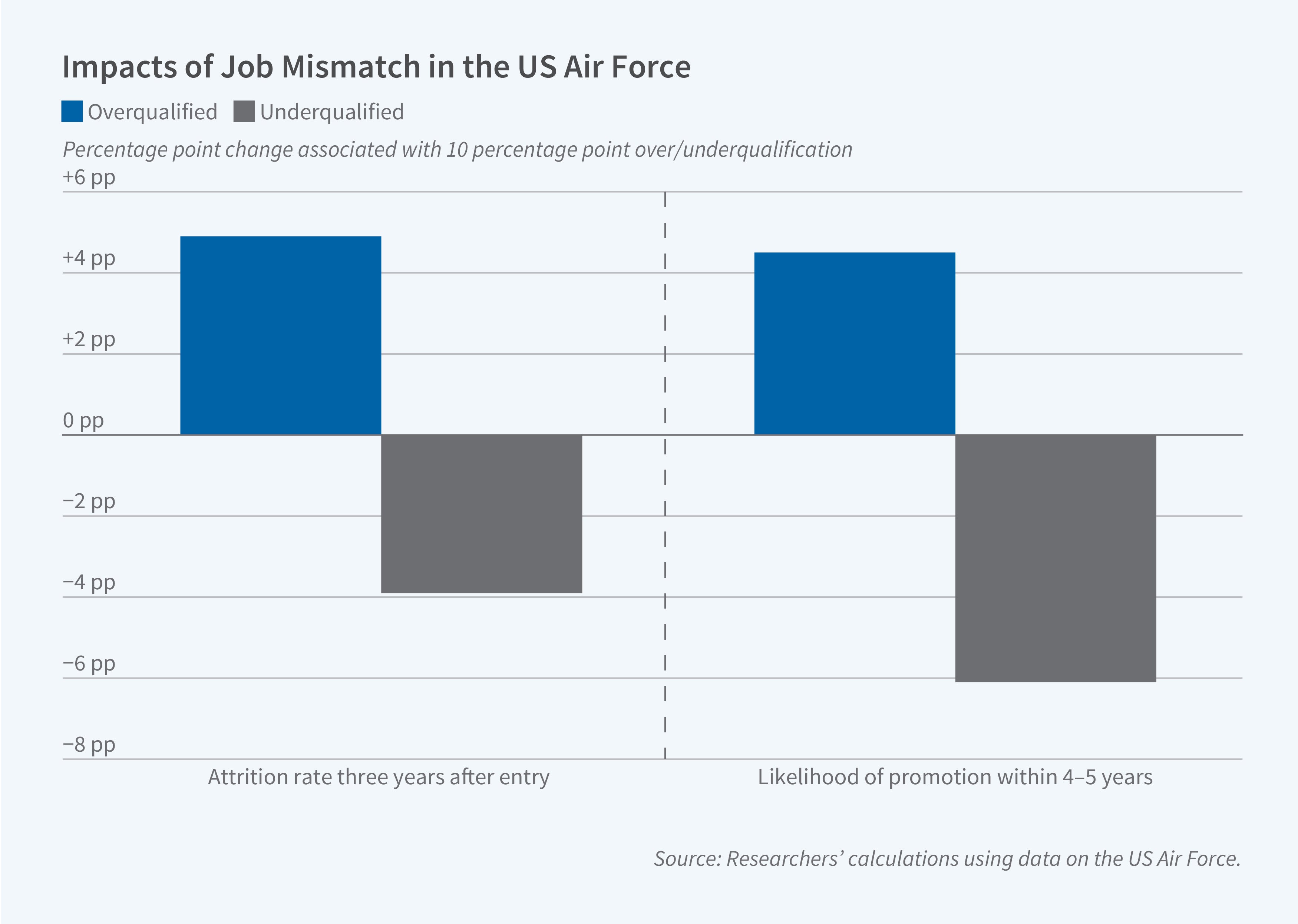

The researchers track individuals for up to five years, observing them during their initial technical training and subsequently on the job. Compared to other workers with the same ability level, being overqualified leads to higher attrition rates, with a 10 percentage point increase in ability surplus decreasing technical training graduation by 1.5 percentage points and increasing three-year attrition by 4.9 percentage points; the baseline attrition rate is 14 percent. Overqualified workers also exhibit more behavioral problems, receive lower performance evaluations, and score worse on tests of general military knowledge. On the positive side, overqualified individuals score better on job-specific skill tests, both during technical training and on the job. The net effect is an advantage when it comes to promotion, with a 10 percentage point increase in ability surplus leading to a 4.5 percentage point increase in the likelihood of promotion relative to a benchmark of 18 percent.

Underqualification produces the opposite effects. It leads to improvements in retention (with a 10 percentage point increase in ability deficit decreasing three-year attrition by 3.9 percentage points), behavior, scores on the test of general military knowledge, and performance evaluations. But underqualified workers also show poorer acquisition of job-specific skills, leading to a disadvantage when it comes to promotion (with a 10 percentage point increase in ability deficit reducing the likelihood of promotion by 6.1 percentage points).

These findings suggest that overqualified individuals invest less effort but still outperform others assigned to the same job. Conversely, underqualified individuals appear more motivated but struggle to compete when evaluated against others with higher abilities. These patterns are consistent with post-service incentives: Overqualified individuals are placed in jobs that have lower civilian earnings potential, while underqualified individuals are placed in positions with higher potential earnings.