Indirect Cost Recovery in Research Funding

For more than 75 years, the federal government has been the largest funder of scientific research at US colleges and universities. Federal science funding includes both direct costs for specific research activities and indirect costs that support the facilities, equipment, and administrative expenses that are needed to conduct these activities.

Federal reimbursement for facilities and administrative (F&A) expenses was introduced during World War II as a way of compensating universities, hospitals, and companies conducting war-related research for expenses associated with lab space, shared instruments, and administrative staff supporting multiple research projects. During the war, the government implemented indirect cost funding at a flat 50 percent of direct costs for universities, and 100 percent for firms, in what was then seen as an imperfect but pragmatic solution to financing the overhead costs of research. After the war ended, federal research funding became a permanent feature of the US innovation system, and indirect cost recovery (ICR) policy evolved. Today, research organizations negotiate institution-specific ICR rates based on actual, audited F&A expenses associated with federal research divided by a direct cost base that excludes certain categories of costs (“modified total direct costs,” or MTDC), subject to some rate caps on specific categories of overhead.

In Indirect Cost Recovery in US Innovation Policy: History, Evidence, and Avenues for Reform (NBER Working Paper 33627), Pierre Azoulay, Daniel P. Gross, and Bhaven N. Sampat examine the role of ICR in US research policy. They focus on the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is the largest funder of biomedical research in the world, and analyze data on 354 research institutions that received an annual average of at least $1 million (in 2023 dollars) in research grants over the 2005–23 period. These institutions account for 91 percent of NIH extramural funding in 2024. Universities comprise 69 percent of these institutions, independent hospitals and medical centers 18 percent, and independent research institutes 13 percent.

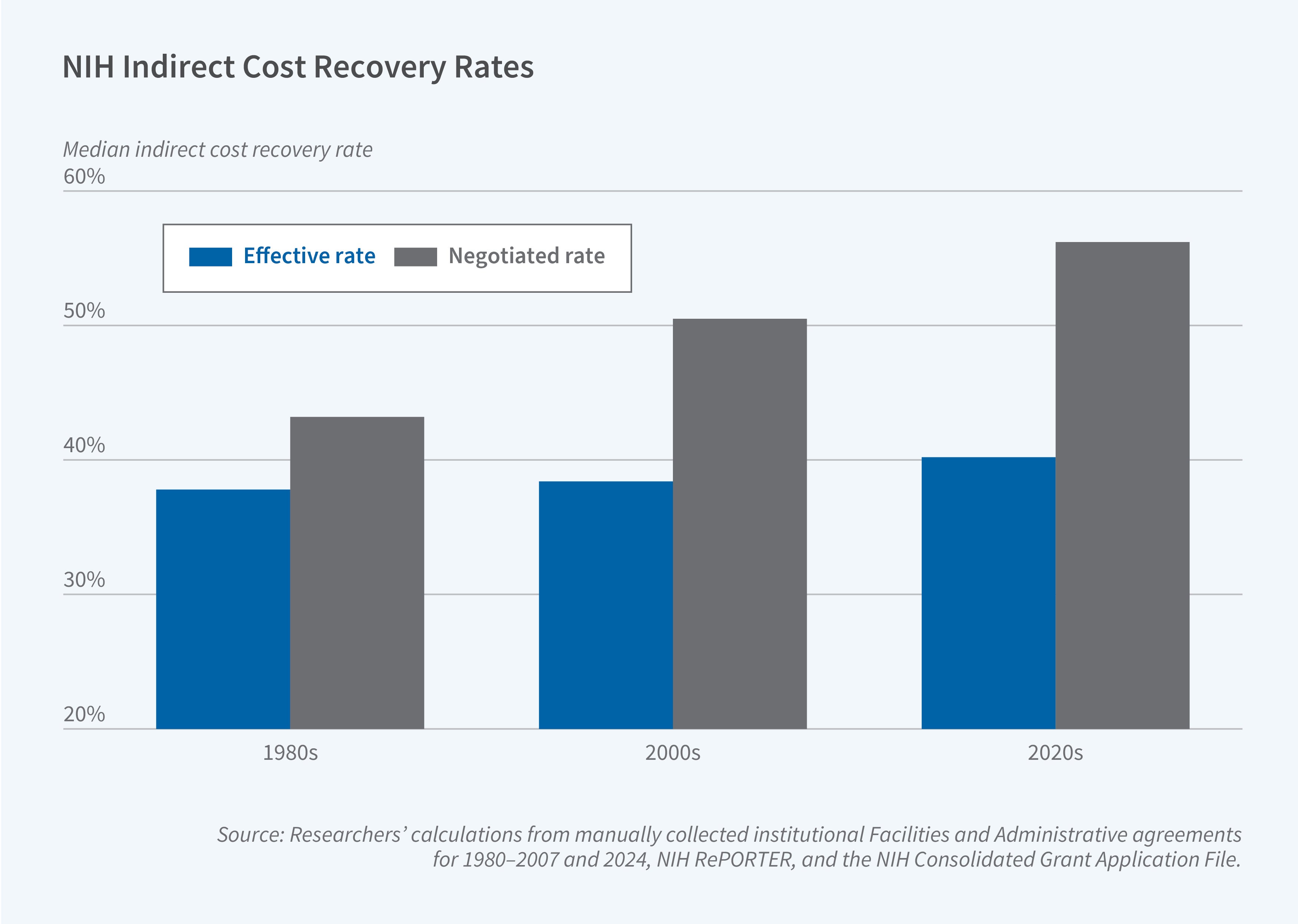

The researchers use these data to present several facts about ICR. Institutions’ effective ICR rates, which are defined as the ratio of indirect cost payments to the total direct costs of research, are substantially lower than negotiated rates. The former averaged 42 percent in 2024, compared with 58 percent for negotiated rates. There is relatively little variation in effective rates across institutions. Universities typically receive indirect cost funding equal to about 40 percent of total direct costs, regardless of rank, endowment size, or research volume.

Effective rates have remained relatively stable for decades despite rising negotiated rates. In the 1980s, negotiated rates were only a few percentage points higher than effective rates, but today the difference is about 16 percentage points. The authors’ evidence suggests that this growing gap is partially a mechanical effect of an increasing share of total direct costs being excluded from the direct cost base on which ICR rates are calculated and applied: intuitively, as the direct costs on which ICR can be collected (MTDC) decline, the negotiated rate must rise in order to cover the same overhead costs.

Using data on current grants to the institutions in their sample, the researchers estimate that shifting to a fixed 15 percent ICR rate for all institutions would result in a 15 to 20 percent decline in NIH funding for most institutions. A dozen institutions would lose more than $100 million annually; collectively, the 354 institutions studied in the paper would experience a loss of nearly $7 billion annually if the policy were put into permanent effect. The institutions facing the largest potential cuts would be those with the strongest links to private sector innovation (as measured using citation-based links to commercial patents). Nearly all institutions with patents on multiple FDA-approved drugs since 2005, for example, have effective ICR rates of at least 30 percent and would experience substantial funding declines if a 15 percent rate were adopted.

The researchers acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1735413 and Grant No. 2420824.